Gurney Elevator, Part One

May 1, 2013

Gurney Elevator Co., founded by Howard F. Gurney in 1905, was an important independent regional manufacturer and recognized as an industry leader in the opening decades of the 20th century. The first “chapters” of the company’s history include what are now considered normative industry practices: the purchase of an existing elevator company and the successful transformation of the old company into a new company. This process included the construction of a state-of-the-art factory, the invention of new elevator systems and the development of an innovative marketing plan. The survival of plans and detailed descriptions of the factory, coupled with the survival of other key sources of information and extensive local press coverage of company activities, permit a thorough investigation of this company and regional elevator manufacturing in the early 20th century.

The story begins in Honesdale, Pennsylvania, in 1850 with the founding of the Honesdale Iron and Agricultural Works by Gilbert Knapp (1813-1893). By 1880, the company was described in a local history as doing “a very large business,” and at some point in the 1880s, they began to manufacture elevators. The company’s success attracted the attention of a group of investors from nearby Scranton, Pennsylvania, who, in early 1895, purchased a controlling interest in the company. The new owners filed a corporate charter in March, and the business was reborn as National Elevator and Machine Co., a name that clearly signaled the focus of the enterprise.

The new owners were an interesting group in that apparently none of them had any experience in the elevator industry. The only evidence of their mechanical abilities is found in a single patent awarded to Walter W. Wood, the company’s general manager: Locking Device for Elevators and Elevator Doors, U.S. Patent No. 553,379 (January 21, 1896). The patent describes a typical safety device designed to ensure the shaft door could not be opened if the car was not present at the landing. The owners’ lack of industry experience did not, however, prove to be a hindrance to success. By November 1897, the company was building hydraulic, electric, belt-powered, hand-powered and carriage elevators, in addition to dumbwaiters. The following year, the Tribune of Scranton reported the company employed “between 60 and 75 hands,” who worked “all the year around.” The newspaper also reported the company’s elevators had found “a ready market in New York City.”

In July 1902, Iron Age reported the company had recently completed the construction of two buildings: a new two-story machine shop (225 X 50 ft.) and foundry (100 X 88 ft.). The magazine also noted the “transmission of power” in the buildings had “been changed from belt to electric motors” and that “a new lighting and generating plant” has also been built on the site. In fact, the previous month, the Tribune had proudly reported the “National Elevator Works. . . claims the honor of being the pioneer elevator company in the United States, to equip their factory throughout with electric motors for the transmission of power.” While this claim cannot be confirmed, there is no question the company continued to grow during this period and that this growth was predicated on utilizing the latest in factory technology. The commercial success associated with these efforts was summed up by Iron Age as follows: “Elevators have been shipped by the company to the Argentine Republic, Brazil and Peru. The domestic trade has gone far beyond what they would have done with their old facilities.”

The company’s commercial success had also not gone unnoticed by other members of the elevator industry. In September 1901, the Tribune reported there was “no truth” to the rumor that “National Elevator Works has been purchased by the Otis Elevator Co.” However, while Otis did not, in fact, purchase National Elevator and Machine, its eventual buyer did have a connection to the country’s largest and best-known firm. In January 1905, Howard F. Gurney (1870-1942) purchased a controlling interest in National Elevator and Machine. Gurney had graduated with a degree in mechanical engineering from the Stevens Institute of Technology in 1892. Immediately following graduation, he went to work for Sprague Elevator Co. Between 1892 and 1898, he progressed steadily through the company’s ranks, working as draftsman, chief craftsman, shop superintendent, construction superintendent and general superintendent of construction.

In 1898, Otis purchased Sprague Elevator. Gurney began his career with Otis as an assistant superintendent of construction and quickly rose to the position of general superintendent of construction “in charge of all work east of Chicago,” which included electric, hydraulic, steam and belt-powered elevators. During his tenure with Otis, Gurney pursued two patents: Safety-Lock for Elevator Shafts, U.S. Patent No. 759,703 (May 10, 1904) and Safety-Catch for Elevator Cars and Counterweights, U.S. Patent No. 763,976 (July 5, 1904). The first patent was granted to Gurney and Bror E. Westlin, who was also an Otis engineer. It is somewhat surprising that Gurney was able to retain his rights to these patents, particularly as Otis had strict policies about patent rights being assigned to the company, rather than to individual inventors. This possible “breaking” of company rules may be seen as an indication Gurney desired greater independence, as well as ownership of his ideas – traits that doubtless contributed to his desire to found his own company.

The March 11, 1905, edition of the Mercantile and Financial Times described Gurney as “one of the best known men” in the elevator industry and predicted his purchase of National Elevator and Machine would lead the business to even greater success:

“The change of proprietorship and management is certainly a progressive one, owing to the fact that Mr. Gurney will personally direct the affairs of the business. It is not too much to say that he is one of the best versed men in this field, and the important work he performed in connection with the development of the Otis business is probably well known. He has, in fact, made a long and thorough study of elevator matters, and will inaugurate in his new company a number of features which he has had in mind, more particularly in connection with the improvement of the already splendid products of the National Elevator Co.”

However, Gurney did not begin this venture as smoothly as he might have liked. He apparently closed the deal in late January. On February 10, the following advertisement appeared in the “Lost & Found” section of the New York Times:

“Lost or Stolen Stock Certificate: On or about February 1st a certificate for four hundred shares of the Capital Stock of the National Elevator & Machine Co., said certificate, No. 68, dated February 1, 1905, and issued in the name of Howard F. Gurney. A reward of $25.00 will be paid for its return or for information leading to its recovery. . . . All persons are hereby warned against any attempted negotiation or transfer of the said certificate by the finder.”

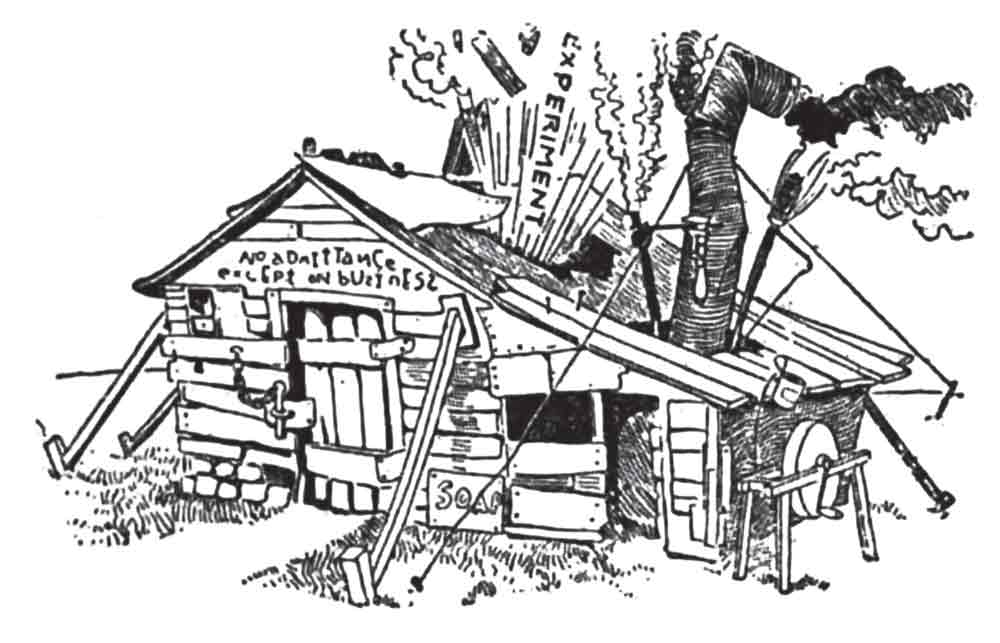

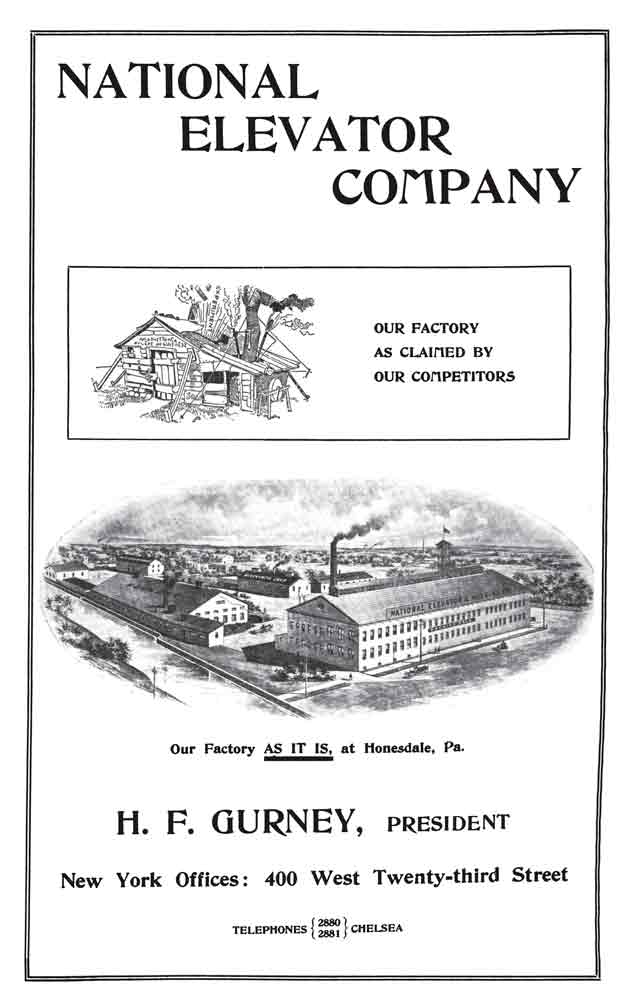

It is safe to assume the certificate was eventually found (or perhaps simply reissued), as Gurney quickly proceeded with the task of improving “the already splendid products of the National Elevator Co.” However, prior to pursuing these improvements, Gurney felt it was necessary to publicly reaffirm the quality of his company and its products. In November 1905, Gurney published an advertisement in the Real Estate Record & Guide (published in New York City) that featured two images. The first was captioned, “Our factory as claimed by our competitors” (Figures 1 and 2). The large drawing, captioned, “Our factory AS IT IS at Honesdale, Pa.,” was a dynamic and accurate depiction of the machine shop, foundry and other company buildings. The presence of this advertisement raises an interesting question: who were the competitors Gurney referred to, and why did he feel the need to respond so directly? The answer may lie in the identity of the consulting engineer Gurney had hired to assist him in his new venture: Eugene R. Carichoff (1860-1938). Carichoff, an electrical engineer, had also been employed at Otis, and it is possible Gurney’s former employer was unhappy at his departure and his taking valued employees with him.

In April 1906, Gurney filed the first patent (awarded the following year) associated with his new business: Electric Elevator, U.S. Patent No. 851,934 (April 30, 1907).

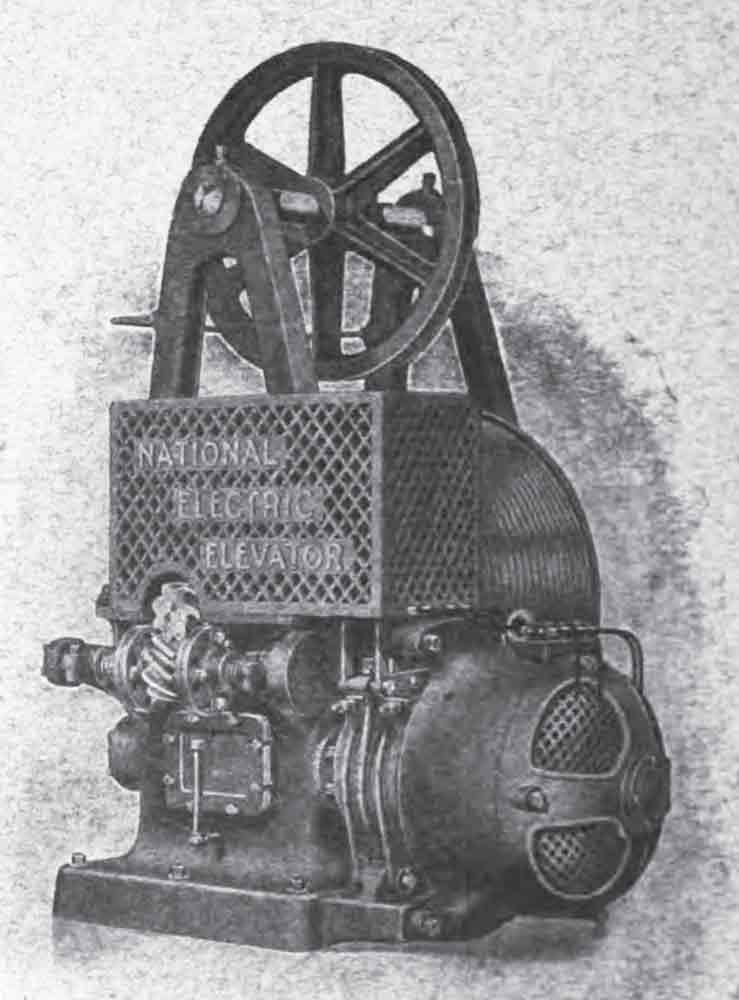

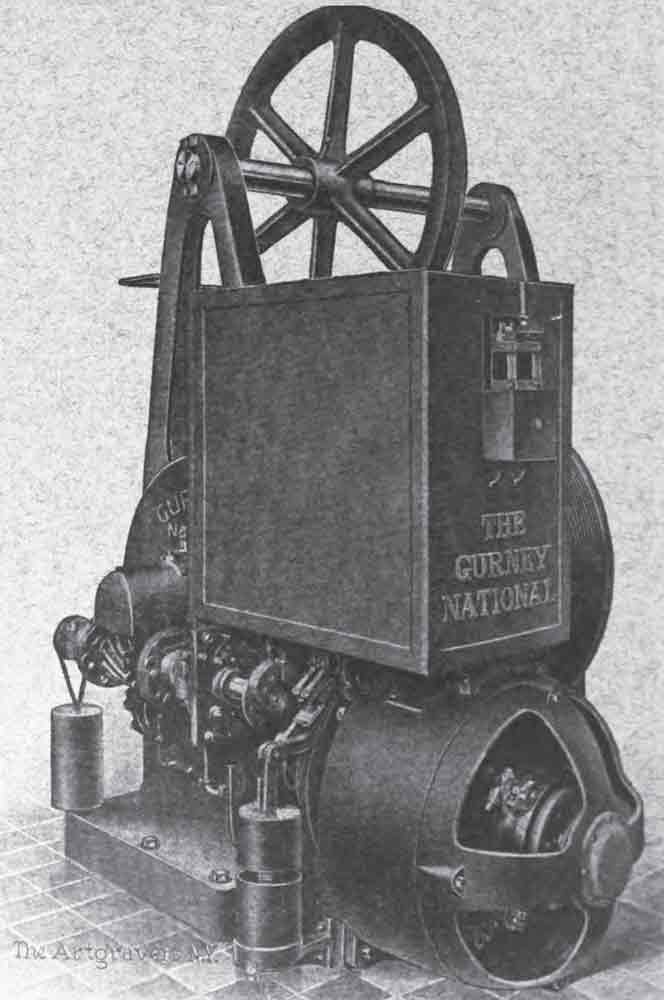

The patent encompassed almost all aspects of an “improved” electric-elevator design and served as the basis for the first new machine marketed by Gurney and National Elevator (Figures 3 and 4). The machine was featured in illustrated advertisements, identified as the “National Electric Elevator” and described as surpassing “all others in safety, reliability, economy of operation and simplicity.” In 1908, the second new machine was launched – Gurney National Electric Elevator – which appears to have been a larger version of the first elevator (Figure 5). Interestingly, both were drum machines. Although this elevator type was standard in the early 1900s, it did not represent the latest in elevator technology, which was the newly developed traction elevator.

Gurney, however, lived up to his reputation as “one of the best versed men” in his industry, and he demonstrated his awareness of the importance of pursuing the development of traction elevators in an interesting way. On April 4, 1910, the Honesdale Citizen reported a new “testing tower” was under construction at National Elevator. The 110-ft.-tall tower, completed in May that year, was described by the newspaper as specifically designed for testing “improved elevator machinery known as traction, which is said to be superior to any now in use.” Gurney’s decision to invest in the new test tower reflected his understanding of the importance of research in product development, which he had learned from his tenure at Otis, the company that had built the first elevator test tower in 1888. This investment was also a clear statement of his commitment to the success of his company, which was further emphasized on June 1, 1911, when the name was changed to Gurney Electric Elevator Co. Part Two of this series will examine the events that followed this name change: the construction of a new factory and the related marketing campaign.

Figure 3: Howard F. Gurney, Electric ElevElectric Elevatorator, U.,S. Patent No. 851,934 (April 30, 1907)

Figure 1: National Elevator advertisement, Real Real EstateEstate RecorRecord & Guide,d & Guide, November 25, 1905

Figure 4: National Electric Elevator (1907)

Figure 5: Gurney National Electric Elevator (1908)

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.