Hart’s Cyclic Elevator, Part Two

May 1, 2012

A detailed examination of published accounts of cyclic-elevator installations

One of the first published accounts of a cyclic elevator installation appeared in the August 27, 1880 issue of British Architect and Northern Engineer. The magazine featured an article on the new Glasgow Herald building (completed in November 1880) including the statement, “An elevator is being erected in the building, of that kind known as the cyclic, or continuous elevator. It is the first of its kind erected in Scotland.” The article also noted, “The elevator is designed by Mr. Fred Hart, and made by Messrs. Hall, of London.” Unfortunately, no other details were provided. However, the fact that the article claimed this elevator was the first of its kind built in Scotland suggests it was not the first cyclic elevator built by J. & E. Hall. This fact is confirmed in a November 29, 1880 Glasgow Herald article, which described the newspaper’s new building. The article reported this elevator was the second cyclic elevator built in U.K., the first having been built for the Mansion House Chambers, London.

The Herald article also contained the following description of its new elevator:

“It consists of a series of cars, 15 in number, which are continually in motion during business hours. It is driven by a gas engine of 8 HP. . . . The maximum speed at which the cars rise or descend is 40 fpm. Owing to the number of cars and their continuous motion, one may ascend to the top of the building or to any of the floors at any moment, without effort or loss of time, and the return journey may be made with the same readiness and comfort.

In addition to promoting its convenience, the Herald claimed, “The mechanism of the elevator is so substantial that almost absolute safety is secure, but we may state that if at any time it should get out of gearing while in use, it at once stops itself automatically.” The article also noted, perhaps in an attempt to calm nervous visitors, “The use of the hoist is, of course, optional.” However, the building’s owners expressed the opinion, “There is hardly any doubt that when it becomes familiar to the public, it will in all cases be preferred to the stair. This is indeed the experience of those who have employed the elevator in London.”

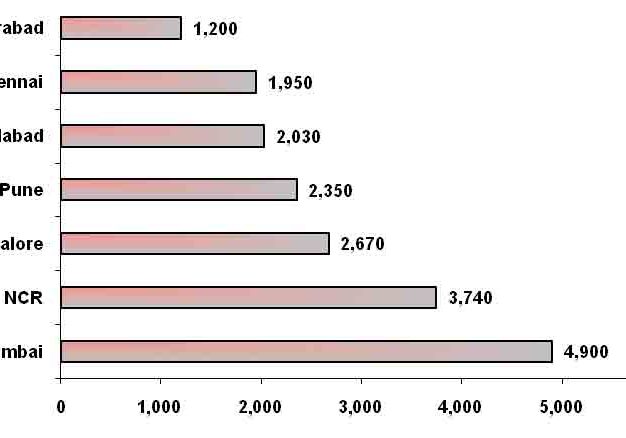

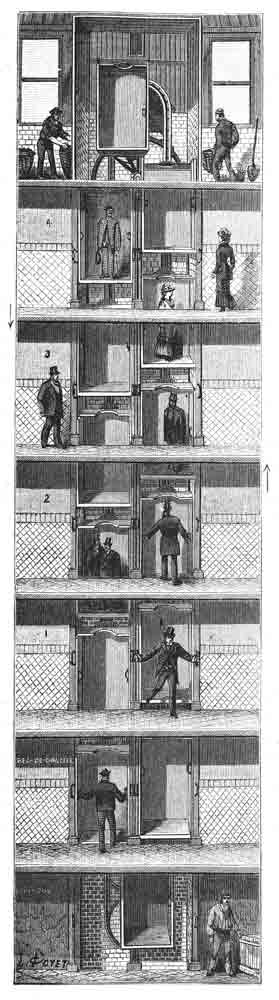

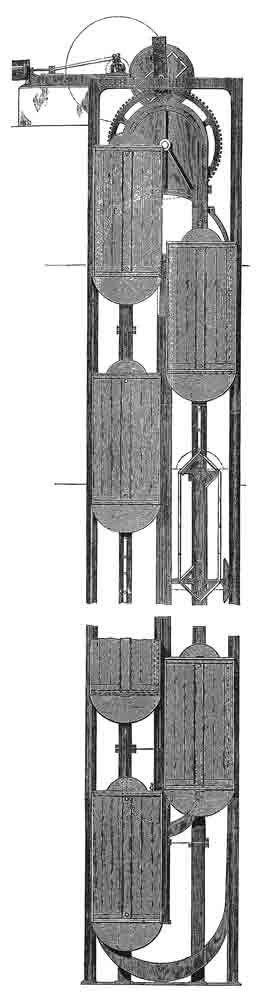

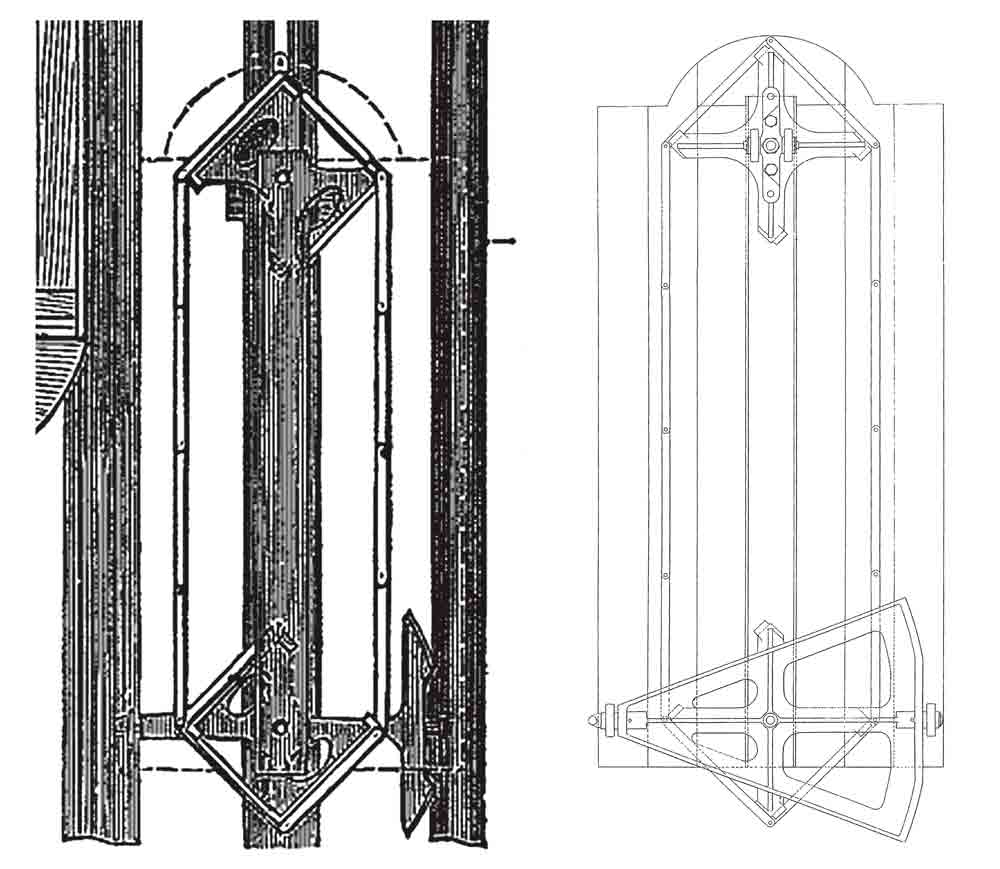

It is of interest that this installation, the second cyclic elevator built in Great Britain, was the first to receive press coverage. In fact, almost two years would pass before the Mansion House Chambers elevator received attention in the professional and popular press. There is, however, no doubt – given the character of this publicity – Frederick Hart’s cyclic elevator had gained the public acceptance and popularity mentioned in the Glasgow Herald. The first article appeared in the July 15, 1882 issue of La Nature magazine. This article featured three engravings by Louis Poyet (an elevation of the elevator from basement to attic, a drawing of the upper landing and a drawing of the engine) that captured the experience of riding the elevator and illustrated its mechanical operation. The latter effort is reflected in the upper-landing drawing, in which the enclosing walls were removed to reveal a lower roller armature and guide rail that closely resembles those found in the second endless-chain design illustrated in Hart’s patent. This drawing includes additional features that, although also found in Hart’s patent drawings, were not mentioned by him: each car and landing was equipped with narrow hinged sills at their edges that acted as safety devices: anything protruding into the shaft or out of the moving car would strike the corresponding hinged sill, which would move upward and, in theory, prevent serious injury to passengers or damage to the elevator.

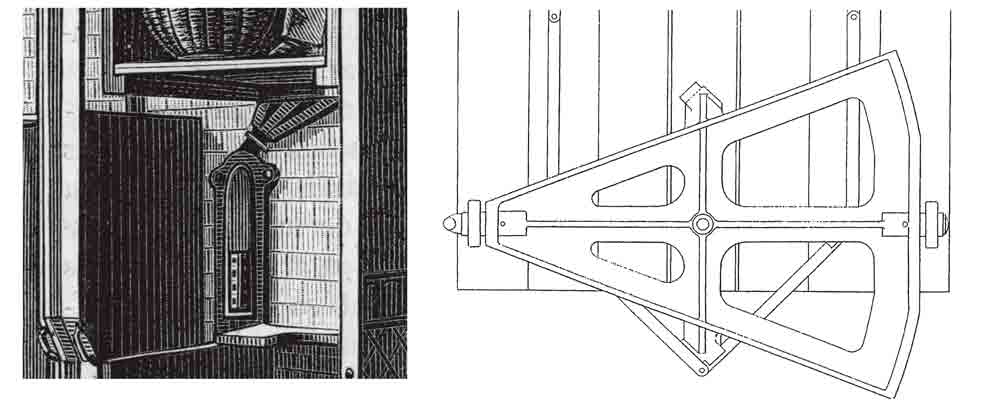

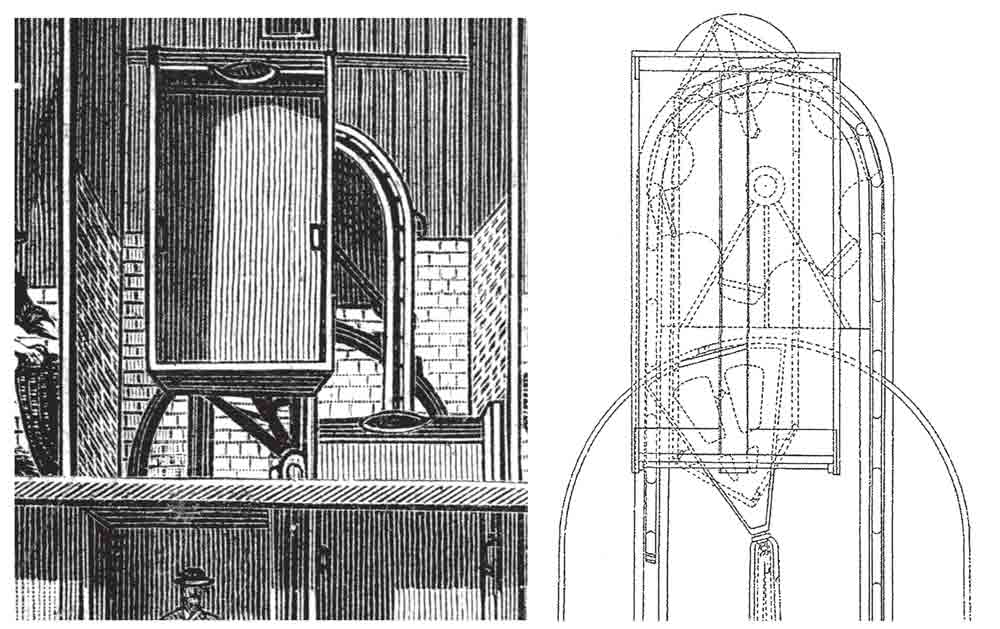

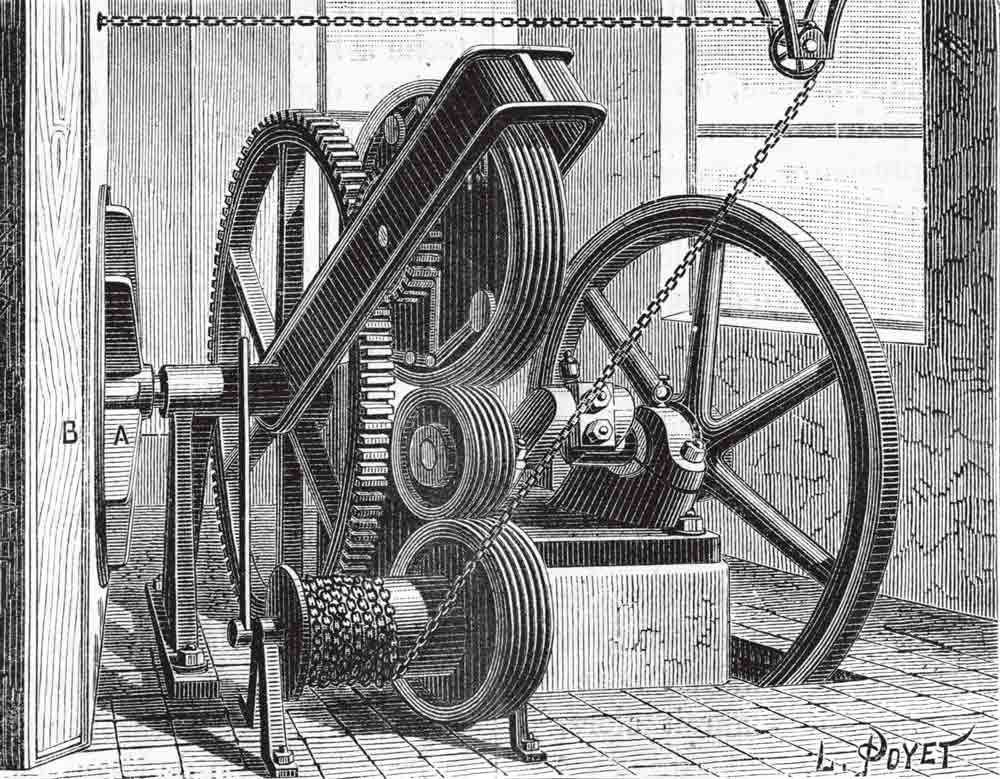

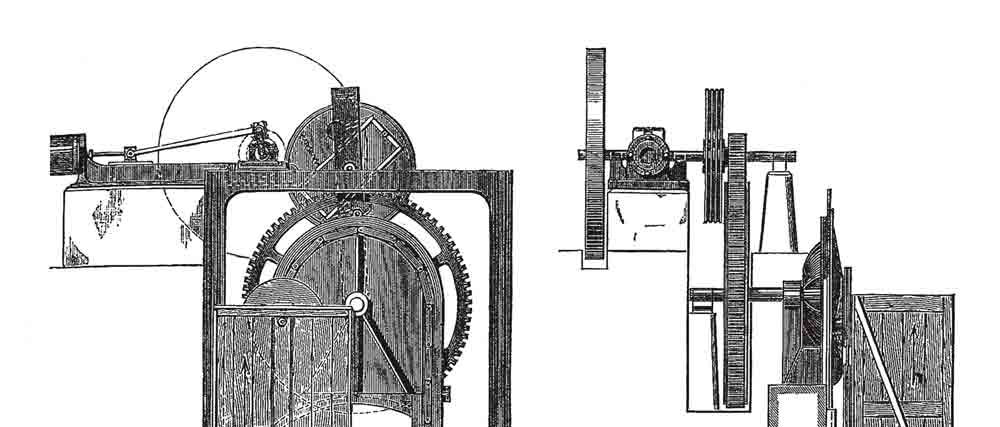

The upper roller guide rails shown in Poyet’s elevation drawing also correspond to those of Hart’s second endless-chain design, which provides additional confirmation that this design guided the elevator’s construction. The elevation drawing also featured 14 cars. Given that 15 cars were used in the Glasgow Herald building, this would appear to be an accurate depiction of the Manson House Chambers installation. Poyet’s detailed drawing of the elevator engine also presents a minor puzzle. While it is very precise, the drawing gives no indication of how the engine was connected to the elevator’s endless chain drive system. In his patent, Hart proposed to drive the chain via a beveled gear system placed on a vertical shaft that extended from a basement engine to the upper chain gear. However, either Hart or J. & E. Hall decided to place the engine in the attic and employ a more conventional direct-geared connection between the engine and endless chain driving gear.

It is important to pause here to remember these extraordinary illustrations appeared in a French magazine devoted to the popularization of scientific knowledge. This prompts several questions: Why this magazine? How and why was this editorial decision made? Where was the comparable British press coverage? Although the La Nature article was quickly translated into English and republished with all of Poyet’s illustrations, this translation appeared in an American publication: the October 7, 1882 issue of the Scientific American Supplement. The first detailed account of the Mansion House Chambers elevator published in England did not appear until the following year in the January 26, 1883 issue of The Engineer. The illustrations that accompanied this article (a front and partial side elevation) were very different from Poyet’s drawings and perhaps reflected the editorial character of The Engineer, which offered its readers a professional rather than a popularized account of contemporary technology. The Engineer’s precise elevation drawings confirm what was found in Poyet’s drawings – the mechanical design of Hart’s elevator closely followed his second endless-chain design. The roller guides follow the same pattern found in the patent drawing, and the detail of the linking-chain mechanism between the upper and lower car rollers also resembles the system illustrated in Hart’s patent.

The Engineer’s drawings also differ from Poyet’s in some minor ways: the lower roller armatures are not shown (they are concealed behind semicircular screens located below the cars), and the front elevation offers a slightly different depiction of the roller guides. The only significant difference between the image sets concerns their representation of the elevator engine. A comparative reading of both sets reveals similar overall design characteristics, as well as several important differences. The Engineer depicts a pronounced difference in elevation between the steam-engine flywheel and the spur gear that drove the chain gear. Additionally, a careful reading of The Engineer’s two elevations reveals a lack of overall consistency in the engine’s representation.

By contrast, Poyet’s drawing, with its greater level of detail and clearer depiction of a relatively compact engine, offers a more convincing representation of the engine’s probable mechanical character. This is supported by the accompanying description in La Nature, which was, in fact, a more thorough account than that offered by The Engineer. The latter simply noted that the elevator was powered by “a small horizontal steam engine,” which employed both “friction and spur gearing.” La Nature described the engine as a kind of “epicycloidal train, in which the movable arm that supports one of the friction wheels makes a slight movement around the axle “A” and proportions the pressure in a certain measure to the mechanical stress exerted.” The magazine also noted the friction gearing drove “a windlass and chain that serves to carry up the coal to feed the boiler” (a feature seen in the drawing’s foreground).

The final piece of evidence, which further confirms our understanding of the operation of Hart’s device, is an account written by American engineer John C. Trautwine, Jr., in which he described a visit to England in 1888. In this lengthy account (published in Proceedings of the Engineer’s Club of Philadelphia), the author described the unique elevator he encountered in the Mansion House Chambers:

“Each cage is a plain wooden box, about 3 ft. square by 7 ft. high, and is intended to accommodate two passengers. . . . Each cage is attached, at its back and near its top, to an endless chain of flat links, which, at the top and bottom of the lift, pass over toothed wheels about 4 ft. in diameter. . . . A vertical guide-bar is fixed to the rear wall of the well and extends from top to bottom of the lift on both the ascending and descending sides. This guide-bar, in cross-section, resembles a box with a narrow opening or slot in its front side, and in it works a T-shaped projection fixed to the back of the cage near its top. The stem of this T passes through the slot in the guide-bar, while the arms of the T projecting right and left within the hollow guide-bar are provided with rollers which bear against its front edges. The guide-bar is bent over in a half circle, from right to left, at the top and bottom of the lift, and thus forms a continuous guide for the T-shaped projection from the top of the cage and for the endless chain to which it is attached. . . a horizontal casting is pivoted to the back of the cage near its bottom. The casting reaches across the width of the cage, and its two ends run in vertical guides fixed to the rear wall of the well. One of these guides, of course, is central, or between the ascending and descending paths of the cages, and is closed at its upper and lower ends. The other guide is behind the opposite side of the cage.”

Trautwine provides additional information in his account that also corroborates the descriptions found in La Nature and The Engineer.

There are, of course, questions that remain unanswered, such as, “How many of these elevators were actually built?” The list of installations found so far, which dates from 1883, mentions only four sites: the Glasgow Herald building, Mansion House Chambers, Bourse Buildings and Kensington Palace Mansions. However, in 1888, Trautwine claimed “a dozen or more” cyclic elevators were operating in London. Finally, there is the question of photographic evidence. A photo of one of these extraordinary elevators is a critical missing piece of evidence. This task (or should I say “treasure hunt”?) I will leave to my colleagues across the pond.

Elevation, Mansion House Chambers elevator: La Nature, July 15, 1882, “Ascenseur Continu de M. Frédéric Hart”

(l-r) Upper landing detail, Mansion House Chambers elevator: La Nature, July 15, 1882, “Ascenseur Continu de M. Frédéric Hart” and detail of car rear elevation, derived from Hart’s patent “Improvements in Elevators” (July 5, 1878)

(l-r) Elevation detail, Mansion House Chambers elevator: La Nature, July 15, 1882, “Ascenseur Continu de M. Frédéric Hart” and detail of schematic elevation, derived from Hart’s patent “Improvements in Elevators” (July 5, 1878)

Elevator engine, Mansion House Chambers elevator: La Nature, July 15, 1882, “Ascenseur Continu de M. Frédéric Hart”

Elevation, Mansion House Chambers elevator: The Engineer, January 26, 1883, “Hart’s Cyclic Elevator: Mansion House Chambers”

(l-r) Elevation detail, Mansion House Chambers elevator: The Engineer, January 26, 1883, “Hart’s Cyclic Elevator: Mansion House Chambers” and detail of car rear elevation, derived from Hart’s patent “Improvements in Elevators” (July 5, 1878)

Elevator engine, Mansion House Chambers elevator: The Engineer, January 26, 1883, “Hart’s Cyclic Elevator: Mansion House Chambers”

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.