Haughton Elevators (1923) Conclusion

Dec 1, 2024

This series conclusion looks at Haughton’s catalog from 1923.

In 1923, the Haughton Elevator & Machine Co. of Toledo, Ohio, published a 32-page illustrated catalog designed to introduce prospective customers to their product line. Part one of this article explored Haughton’s characterizations of their elevator equipment as discussed and illustrated in their catalog. In addition to presenting Haughton’s elevator systems, the catalog included a detailed guide to the writing of elevator specifications, as well as information on wiring, elevator speeds, the typical space required for traction elevator installations and Haughton’s post-installation services. This conclusion examines these topics.

The section titled To Assist You in Preparing Elevator Specifications is, perhaps, the most interesting. It addresses 24 specifications intended to cover all aspects of an elevator’s installation.[1] The material was presented in the form of a “typical elevator specification, which may be adapted to suit almost any condition.” In fact, much of the material appears to derive from an actual Haughton specification, a fact evident in the text of the section titled Work Included:

“The elevator contractor shall furnish all labor, and the necessary repairs and material required for the complete installation of four electric traction passenger elevators, including supporting beams, guides, signals, safety devices, electric wiring from elevator control boards to motors and electric interlocks.”

The following, related section, Work By Others, was more generic: “Power wiring to each elevator control board, lighting outlet at center of hatches, shafts, pits, enclosure and concrete floors in penthouse will be furnished by others.” The attempt to blend a specific example with general information occasionally resulted in an awkward juxtaposition of content, as was illustrated by the section titled Plans: “Blueprints Nos. 1 to 15 accompany and are to form a part of this specification. The elevator contractor shall notify the architect in writing of any change in the structure, which may be required to accommodate the equipment included in the proposal.” The “blue prints” were not included in the catalog, thus their content and specific relationship to their proposed site is unknown.

Six specifications addressed the delineation of responsibilities between the elevator and building contractors. The building contractor was responsible for constructing shafts that were “plumb from top to bottom to within a variation of 1 in.,” and for ensuring that the penthouse featured a concrete floor for the hoisting engines. Haughton was responsible for furnishing “all necessary steel beams for the support of hoisting engines, sheaves or other equipment in connection with elevators.” Haughton was also responsible for all “cutting and patching”:

“All cutting and drilling of structure necessary for the installation of apparatus included in this specification to be done by the elevator contractor. Patching of plasterwork damaged through work necessary in placing fastenings is to be done by elevator contractor. Any removal of walls, floors or partitions required for placing elevator machinery, and the necessary repairs, to be done at the expense of elevator contractor.”

The installation of required “inserts and fastenings” was a collaborative effort between Haughton, the architect and the building contractor:

“Inserts will be placed in the concrete walls of hatches at floors during construction for the support of car and counterweight guides if detailed drawings showing desired location of same are submitted to architect within one week from date of award of contract, otherwise elevator contractor will provide the necessary guide fastenings at his own expense. Elevator contractor shall provide all necessary bolts and fastening devices for the proper installation of his apparatus. No wood plugs will be permitted. Expansion bolts are not to be used for guide fastenings where possible to use through bolts, unless approved by the architect’s superintendent of construction.”

While the specification acknowledges that it was Haughton’s responsibility to furnish detailed drawings “within one week from date of award of contract,” the wording stating the penalty for failing to do so appears to include an error. It seems likely that the correct wording would have been that the “elevator contractor will provide the necessary inserts at his own expense.” This reading seems accurate, particularly given the clarity of the next sentences, which note that Haughton would provide all “necessary bolts and fastening devices for the proper installation” of the elevator guides. The prohibition on the use of “wood plugs” (a 19th century means of securing guide rail supports) and expansion bolts is also of interest. The elevator and counterweight guides supported by the inserts and fastenings were to be:

“smoothly planed steel tees rigidly supported to masonry in such manner as to provide ample support for car in case of failure of hoisting cables and resultant stopping of car by safety clamps, and shall not show distortion or variation from a straight line when car is eccentrically loaded to its full capacity on one half of platform. Guides are to be smooth and noiseless in operation and end joints are to be tongued and grooved.”

The reference to eccentric loading as a means of testing the guide rails raises the question of the nature of the normative testing that was typically done to ensure proper installation. The only other reference to testing stated that the “elevator contractor is to make load and speed tests as directed by the architect.” Placing the responsibility on the architect to determine the appropriate tests to verify satisfactory elevator operation was an interesting choice.

The remaining specifications addressed current, use during construction, location of machines, load, speed and travel, hoisting engine, counterweight, car frame, cars, operating device, safety devices, signals, interlocks, painting, laws and ordinances and data to accompany proposal. The reference to the elevator’s use during construction was presented in an intriguing manner:

“If any apparatus installed by this contractor is used for hoisting during construction such use is to be by agreement of elevator contractor and other contractors. The elevator contractor shall furnish a capable man to operate the elevator at all times and be responsible for all damage which may be caused thereby either to his apparatus or to the structure and deliver the elevator equipment to the owner in first-class condition.”

While the requirement that Haughton would furnish an elevator operator made sense, it is surprising that they accepted responsibility for “all damages” that might occur during the building’s construction. The specification regarding laws and ordinances serves as reminder that, in 1923, the first edition of A17.1 was only two years old and had not yet enjoyed widespread adoption:

“All parts of equipment installed under this contract shall comply with the rules and ordinances of the city and State wherein elevator is to be installed applying to this class of apparatus and a certificate of inspection from the Elevator Inspection Department shall be delivered to the owner before final payment.”

Nonetheless, Haughton’s statement that final payment was not due until they had provided the owner with a “certificate of inspection from the Elevator Inspection Department,” was evidence of the company’s commitment to safety.

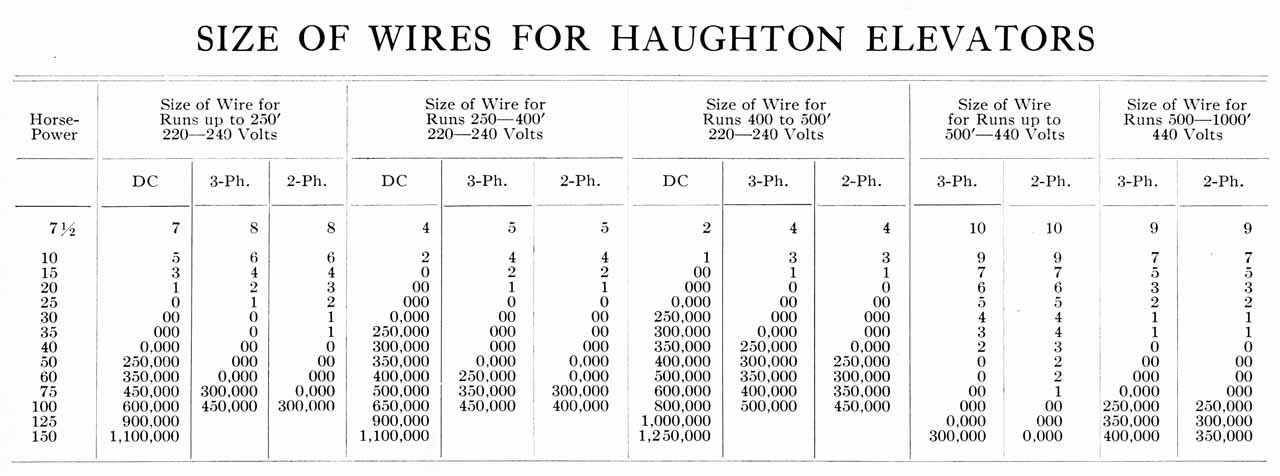

A somewhat surprising data set included in Haughton’s catalog was information regarding electrical wiring. This included a set of tables that provided the “minimum size of wire desirable for one Haughton elevator” at a range of voltages, wire runs and motor horse powers (Figure 1). The table only included data for DC installations. For AC installations, Haughton recommended the use of 440 V for motors over 40 hp. Haughton also noted that: “As Underwriters do not, as yet, give a wiring standard for intermittent or elevator service, it is necessary in wiring for a bank of elevators to wire for the sum of the full load horse powers, plus the starting of the largest motor.” Given that the table only provided data for one elevator, the catalog included recommendations on how the data should be extrapolated for multiple elevators:

“For two elevators, wire equal to double the above table.

For three elevators, wire equal to 85% of three times the above table.

For four elevators, wire equal to 75% of four times the above table.

For six elevators, wire equal to 62% of six times the above table.

For eight elevators, wire equal to 54% of eight times the above table.

For 10 or more elevators, wire equal to 50% of ten or more times the above table.”

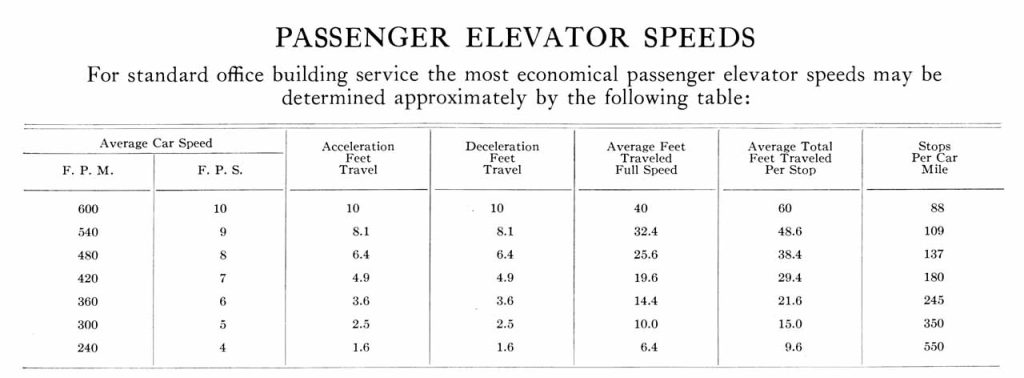

Haughton also provided information on passenger elevator speeds in a table intended to help customers select “the most economical” elevators for use in a “standard office building.” This information was presented in a table that listed the average car speed (in feet-per-minute and feet-per-second), distance traveled during acceleration, distance traveled during deceleration, average feet traveled at full speed, total feet traveled and average stops per-car-mile (Figure 2). Prospective customers were advised that:

“A short study of the table will show generally that 600 ft/min is warranted only for special express service, and that the standard locals for office buildings range from 400 to 550 ft/min; also that 250 to 350 ft/min is best suited for department store service, when stopping at all floors. While 400 ft/min may be installed for such service, this speed increases the operating cost and does not increase the service rendered unless it is not necessary to stop at every floor.”

Haughton also noted that: “In determining the number of elevators necessary for a building, two requirements must always be checked; first, the time desired between elevator cars leaving the first floor; and second, the ability to handle the traffic at the rush hours.” Given the detailed data provided in the table, it is interesting that Haughton chose not to include formulas for determining elevator requirements (by the early 1920s a number of standard formulas were in use).

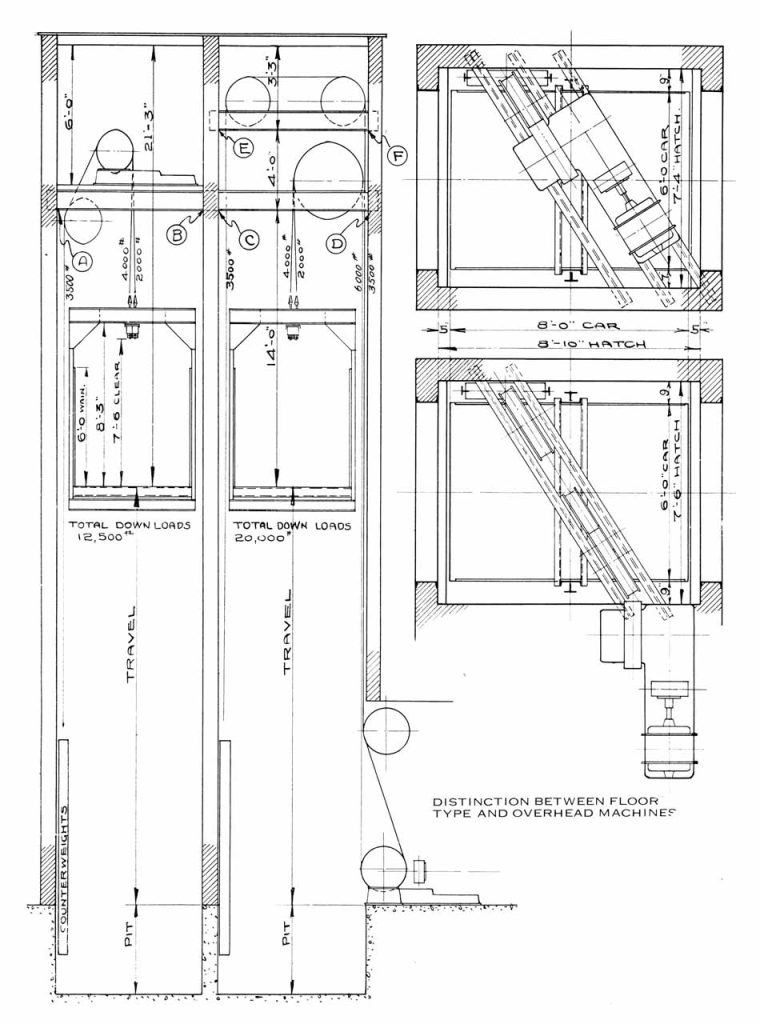

Haughton also provided sections and plans that illustrated the typical “amount of room required” for “floor and overhead installations” of traction machines. The sections were placed side-by-side (floor machine on the right and overhead machine on the left) (Figure 3). The plans illustrated the relative motor placements and required overhead work. Haughton noted that “the floor machine requires the same distance above the top landing as the overhead type,” and they recommended “the overhead type of installation as compared with the floor machine.”

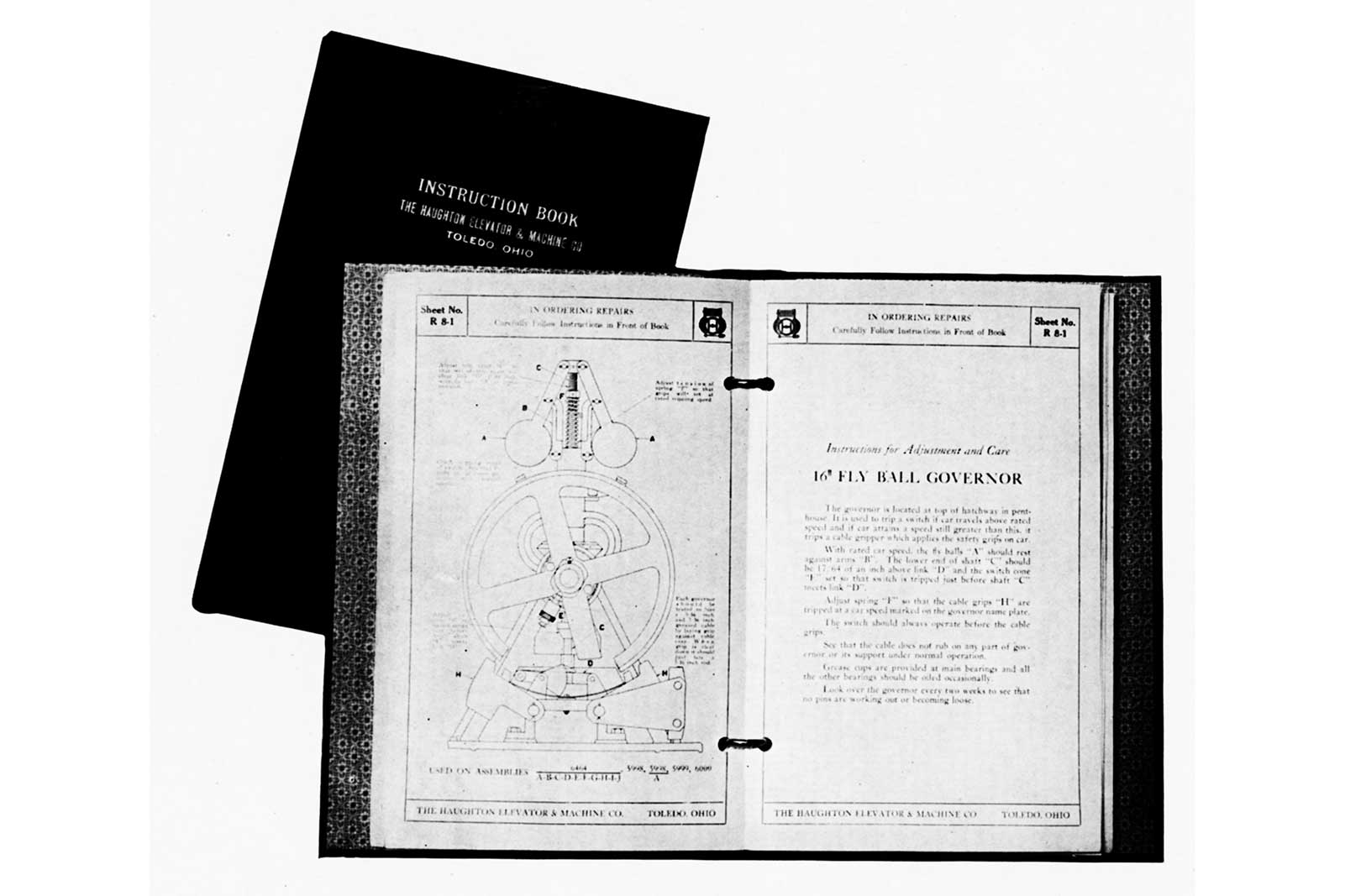

The catalog concluded with information on what Haughton referred to as their Parts Book, which was provided to clients upon the installation’s completion.

The Parts Book, also identified as an Instruction Book in a catalog illustration, contained detailed information on the installed machines and included “pictures and descriptions of each part, and complete instructions for oiling, care and adjustments.” The purpose of the book was two-fold:

“It gives the buyer of a Haughton Elevator a great advantage in enabling him to do much of the work of adjustments and small repairs without outside help. (And) it does away with practically all the troubles ordinarily experienced in ordering parts for repairs and replacements.”

The catalog’s illustration of a typical Haughton Parts Book depicted a drawing of a fly-ball governor, which was accompanied by a detailed description (Figure 4). Careful inspection of the image reveals that the information is presented on a single sheet labeled R 8-1. This organizational system was similar to that used by other manufacturers, and Haughton appears to have followed typical vertical-transportation (VT) industry practice in providing this type of material to their clients.

This brief examination of Haughton’s 1923 catalog provides insights into the business practices of an important regional elevator manufacturer and sheds light on the broader characteristics of the American VT landscape in the early 1920s. Future articles will continue the exploration of VT industry business practices, including estimates, contract proposals, specifications and service agreements.

Reference

[1] Haughton Elevators, Haughton Elevator & Machine Co. (1923). Note: All quotes derive from this source.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.