Heurtebise Elevator Construction Co.

May 1, 2015

A unique glimpse into the world of 19th-century French elevator manufacturing

Between 1876 and 1885, the French publication Les Grandes Usines: Études Industrielles en France et a L’étranger published detailed accounts of various French industries, their products and their factories. (In 1884, the magazine’s name was changed to Les Grandes Usines de Turgan: Revue Periodique des Arts Industriels). The feature article in the January 1885 issue was titled “Des Ascenseurs Heurtebise Société Anonyme de Construction” (“The Heurtebise Elevator Construction Company”). The illustrated article included an overview of elevator use in France, descriptions of the Heurtebise factories, descriptions of the hydraulic elevators they manufactured and a brief history of the company. This article provides a unique glimpse into the world of 19th-century French elevator manufacturing.

The article’s unknown author reported that, while the use of freight hoists in industrial buildings and warehouses was quite common, the use of passenger elevators was less common. The primary reasons behind the slower adoption of passenger elevators were concerns about safety. Although the author acknowledged that “for many years, accidents have discredited the elevator,” he reminded his readers that “no device is perfect when first introduced.” In early French elevators, the car was suspended by chains, which were attached to hydraulic engines, and the movement of the hydraulic pistons controlled the vertical movement of the car. The primary defects of these elevators included concerns about the safety of the chains (they could break) as well as their impact on the elevator’s operation: the “passage of the chain” over the sheave produced an “unpleasant and frightening jolting” of the car.

The solution to these problems was the direct-plunger elevator. However, this system presented its own problem: the need to steadily increase power as the plunger or piston ascended. Ironically, this was solved by the addition of a counterweight attached to the car via a chain. Although this reduced the power required to raise the plunger, it reintroduced the “unpleasant and frightening jolting” of the car and presented a new safety concern: if the piston failed, the counterweight could pull the car upward, potentially crashing into the overhead sheaves. In 1878, this occurred in the Grand Hotel in Paris, and three passengers were killed. (This tragic accident received extensive press coverage throughout Europe and the U.S.)

The elevators invented and manufactured by Heurtebise were perceived to have successfully overcome the problems of earlier systems with regard to safe and economical operation. French engineer Emile Heurtebise founded the company in the late 1860s. Heurtebise was awarded nine hydraulic elevator patents between 1877 and 1889, and he was an active participant in several French industrial expositions: he displayed his elevators in 1872 in Lyon (winning gold and silver medals), in 1878 in Paris (winning a sliver medal) and in 1884 in Nice. These exhibitions made his elevators well known throughout France. They were also featured in numerous publications, including an illustrated article about Heurtebise’s display at Nice, which appeared in the April 5, 1884, issue of Le Génie Civil.

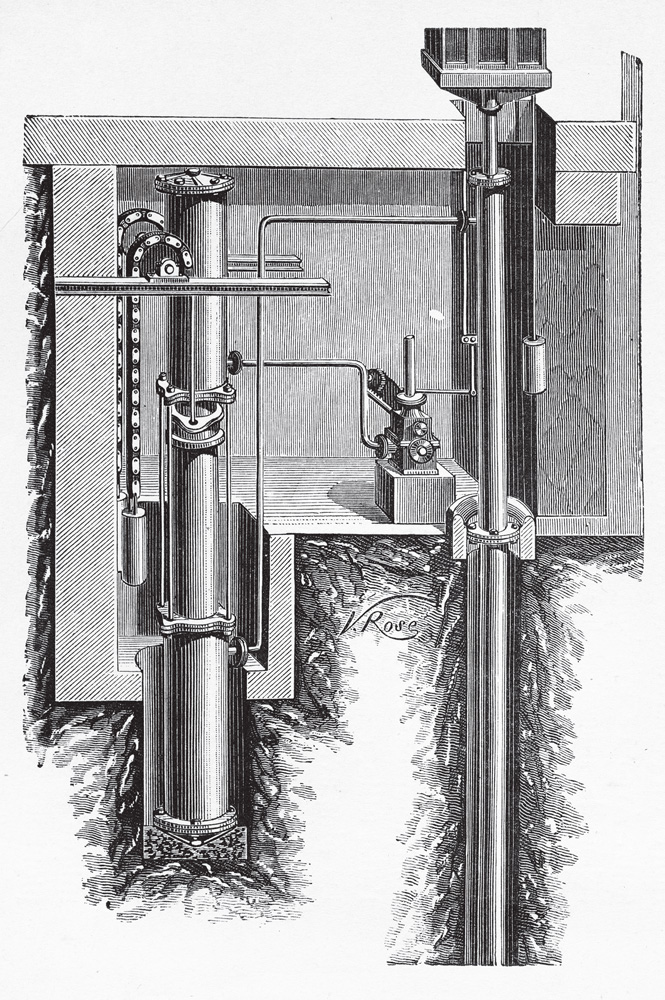

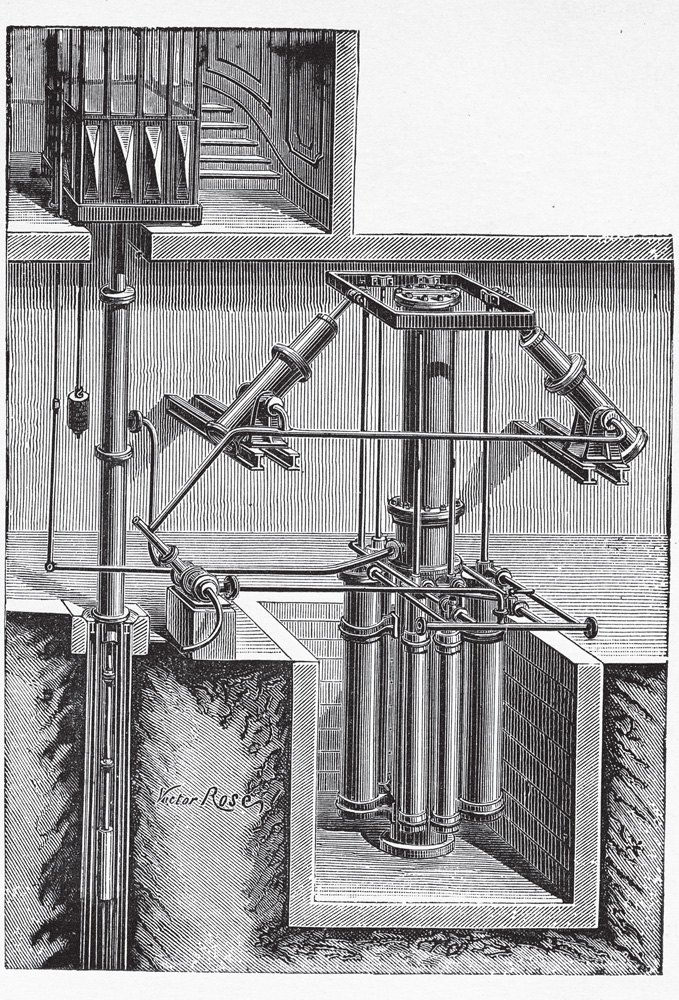

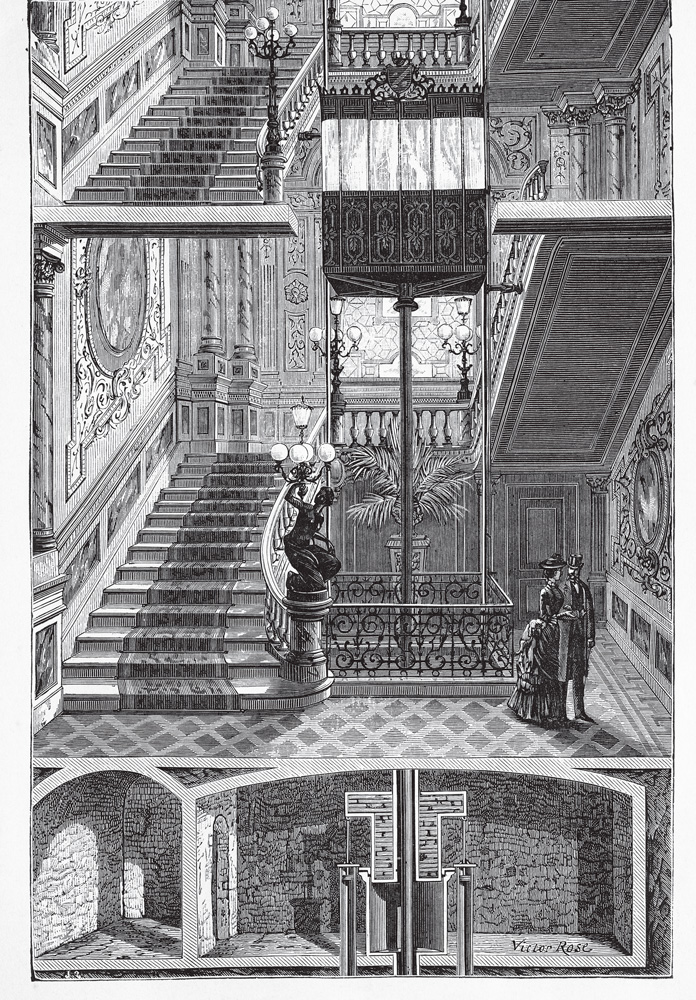

By the mid 1880s, Heurtebise manufactured a variety of hydraulic elevators, all of which were direct-plunger machines that avoided the use of counterweights and chains, and instead relied on various hydraulic devices to provide additional power. The first type he developed, L’ascenseur à Compensateur (the Compensator Elevator) employed a compensating device in equilibrium with the car piston: as the compensator piston went down, the car went up (Figure 1). The system was designed such that the compensator’s stroke was typically only “1/4 or 1/10” that of the car piston. Heurtebise also built a variable-pressure compensator that used multiple smaller pistons clustered around the main cylinder. The additional pistons were called into action as needed. This system was also equipped with two “oscillating cylinders,” which provided additional power and were located at the top of the main compensator (Figure 2). The oscillating cylinders were also used on a model that employed only one compensating cylinder (Figure 3). Finally, Heurtebise manufactured an elevator that featured a compensator located directly below the car and built around the car piston (Figure 4). Heurtebise’s car pistons were constructed of copper with an inner iron core. This construction was described as being lighter than traditional cast-iron pistons and as producing less friction.

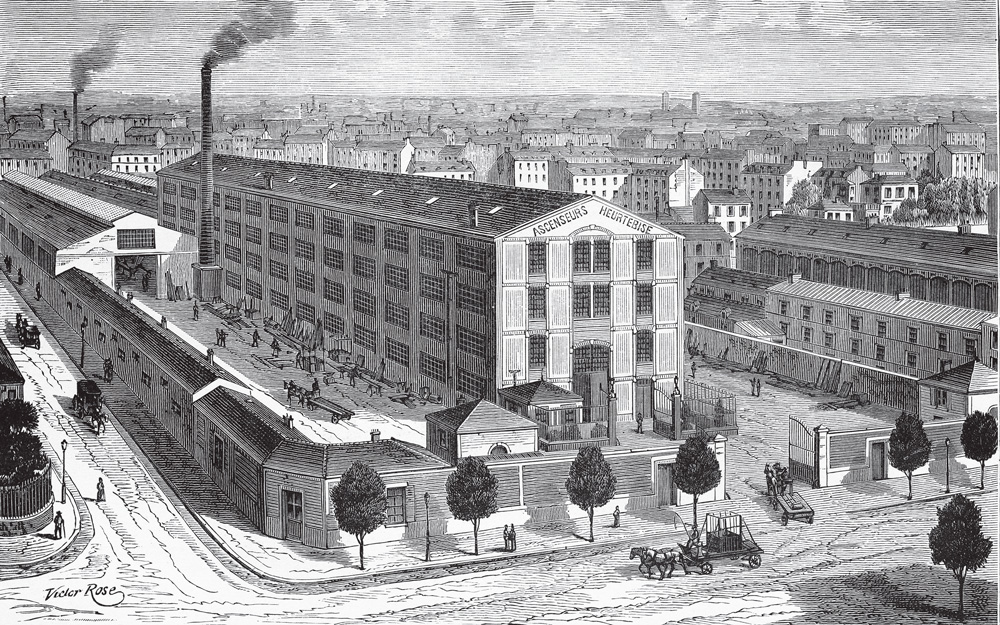

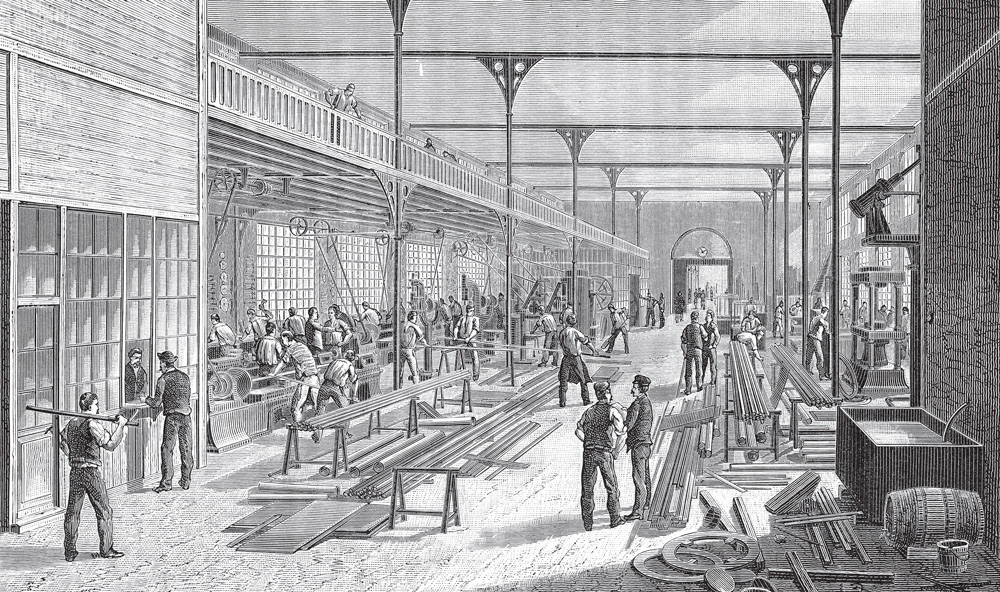

The elegant Heurtebise elevator car depicted in Figure 4 and its setting (likely the stairwell of an important urban hotel) meets our normative expectations for these machines. However, the 1885 article on Heurtebise’s elevators included an illustration of a different type of machine designed for a very different setting: a hospital. Although the three-part drawing, which depicts three separate floors, is somewhat disjointed, it effectively illustrates a large elevator designed to transport patients on beds or stretchers between floors (Figure 5). The article is also accompanied by two additional, equally unique images. These depict the exterior and interior of the Heurtebise factory located on the Boulevard Gouvion-Saint-Cyr in Paris (Figures 6 and 7). The factory was designed primarily for the assembly of hydraulic elevators and featured an expansive interior workspace. The building also included a “demonstration elevator” used to “study” design improvements prior to their implementation. The demonstration or test elevator appears to have been a version of Heurtebise’s oscillating cylinder design. (One of the oscillating cylinders may be seen on the far right of the interior image.)

The elevators invented and manufactured by Heurtebise were perceived to have successfully overcome the problems of earlier systems with regard to safe and economical operation.

In addition to the Paris assembly plant, Heurtebise operated two additional factories. The factory devoted to manufacturing the elevator’s hydraulic components was located at Auxerre (approximately 175 km southeast of Paris). By 1867, Heurtebise had purchased an old foundry, which had been built in 1830. By 1876, he had completed the modifications necessary to begin producing elevator parts. The modifications included installing a 20-T moving crane, new forges, new fitting workshops and a modeling shop. The complex covered approximately 4,000 m2, 25% of which was devoted to the foundries. In addition to his factories in Paris and Auxerre, Heurtebise also had a branch factory in Nice. In 1885, the company’s total workforce was 200 men: 100 in Paris, 50 in Auxerre and 50 in Nice. The company’s annual income was approximately 800,000 francs, and its total worth was estimated at 1.7 million francs. Between the late 1860s and 1885, the company produced more than 600 elevators with an estimated value of 7 million francs. Given this apparent financial health and success, it is somewhat surprising to find that Heurtebise filed for bankruptcy in early 1886. (The reasons for the sudden change of fortune are unknown at this time and may be the subject of a future article.)

The 1885 account of Heurtebise Elevator Construction provides a unique glimpse into the world of 19th-century French elevator manufacturing. It also raises interesting questions about national differences in elevator production. It is of interest that the article’s brief overview of French elevators focused solely on hydraulic systems and consistently referred to the use of chains — not ropes — to support the car. The article also reported that a Heurtebise elevator with a 15-m rise and capacity of 4000 kg had “recently been shipped to the colonies.” The shipment included the elevator and all necessary “accessory devices, such as pumps, pressure accumulators.” Unfortunately, the specific French colony was not identified; nonetheless, it is fascinating to consider the deployment of this technology in a colonial setting in the mid 1880s.

Finally, given the company’s scale of production — more than 600 elevators manufactured by 1885 — I am curious to know if any of these remarkable machines are still in existence. Thus, as I have done in the past with American readers of ELEVATOR WORLD — I respectfully ask French EW readers to consider sharing information about Heurtebise (or other 19th century French manufacturers) with your humble elevator historian at [email protected].

Figure 1: Heurtebise elevator with compensating device

Figure 2: Heurtebise elevator with variable water-pressure compensating device and oscillating cylinders

Figure 3: Heurtebise elevator with compensating device and oscillating cylinders

Figure 4: Heurtebise elevator with compensating device under car

Figure 5: Heurtebise hospital elevator

Figure 7: Interior of Heurtebise Elevator Construction factory in Paris

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.