Hoists, Teagles and Safety in the Early 20th Century, Part Two

Nov 1, 2011

A continued look at the role of teagles and hoists in early elevators

Last month’s article introduced W. Sydney Smith’s Report on the Construction, Arrangement, and Fencing of Hoists and Teagles of 1904. This article will continue the discussion of this important work and address some of the safety devices Smith covered in the second half of his report. The examination of this material, which consisted of both written descriptions and illustrations, permits a thorough understanding of British industrial lift practices in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Smith divided his presentation into two sections – one concerning “non-automatic” and automatic hoist doors, and one concerning “safety gears.” Smith noted that if, in the section of his report devoted to “Automatic Hoist Doors,” he had attempted to provide a “description of all known varieties,” the result would have been “too bulky a volume”; thus, he decided to focus his attention on the “general types” of hoist doors in use.

It is not surprising that Smith claimed that the best practice concerning non-automatic and automatically operated hoist doors was to utilize systems that employed a locking mechanism that ensured the doors could only be opened from inside the cage and/or while stopped at a landing. However, he also stated that common practice often permitted the use of simple hinged bars or rods that limited access to the shaft in only a minimal fashion, a practice he claimed “should always be condemned.” Equally dangerous was the use of low doors:

“With bars of any description or low doors there is always the danger of the head or upper part of the body being caught between the bottom of the descending cage and the top of the bar or door. If these are fixed close to the edge of the hoist well a guillotine action at once follows if a person be leaning or looking over the fence, and severe crushes or internal injuries are always liable to ensue even if the accident is not immediately fatal. . . . Doors of any value for safety should be not less than 5 ft., 6 in. in height as a minimum, and preferably they should be the full height of the hoist opening.”

Smith provided descriptions and illustrations of 11 semi- and fully automatic door systems, which embraced a variety of approaches and were designed by an eclectic group of inventors and manufacturers. These devices included:

- Knowles’ Safety Doors

- Heywood & McGee’s Hoist Platforms

- Lloyd & Hopkinson’s Safety Doors

- Higginbottom’s Automatic Locking Gate

- Barker’s Automatic Locking Gate

- Newsome’s Automatic Hoist Guard

- Rigby & Taylor’s Automatic Hoist door

- Botterill’s Automatic Hoist gate

- Bostwick Collapsible Gate with Automatic Gear

- Waygood’s Automatic Safety Doors

- Etchell’s Automatic Doors

Both Knowles’ and Heywood & McGee’s safety systems had been in use for several years and had, in fact, been featured in the 1886 Report of the Chief Inspector of Factories and Workshops. The former was characterized as a semiautomatic system in that the door was linked to shipper rope such that, when the door was open, the shipper rope could not be moved. Heywood & McGee’s Hoist Platforms had been invented and patented by Abel Heywood & E. McGee in 1886. This system employed a series of platforms composed of “stout wire netting,” which were automatically deployed at each floor level as the hoist cage traveled through the shaft. However, while this system effectively prevented workers from falling down the shaft, the typical lack of a door or gate (which was not required with this system) was viewed as a significant safety hazard.

It is of interest to note that neither of these devices was designed by a lift or hoist manufacturer. The Knowles’ Safety Door had been patented by William Knowles & Co., owner and operator of the Hartford Mill in Bolton, which specialized in cotton spinning. Abel Heywood was a principle owner of Abel Heywood & Son of Manchester, a well-known printing and publishing firm. While it was not unusual for individuals outside the vertical-transportation industry to patent safety devices (or even complete elevator systems), the fact that these two systems were designed, patented, built and perhaps even marketed raises interesting questions about the British lift industry of the late 19th century. Some of these same questions may be asked of Lloyd & Hopkinson’s Safety Doors, Botterill’s Automatic Hoist Gate and Patent Flexible Hoist Guard, and Rigby & Taylor’s Automatic Hoist door. At this point, only the following is known about the inventors of these devices: Albert H. Lloyd and Charles Hopkinson of Manchester were civil engineers; John Botterill of Leeds was a mechanical engineer; and John Rigby and William R. Taylor were from Bolton (occupations unknown). However, all of these devices had been patented and were used in British factories, and several of the inventors had multiple lift patents, which indicates a sustained interest in this subject.

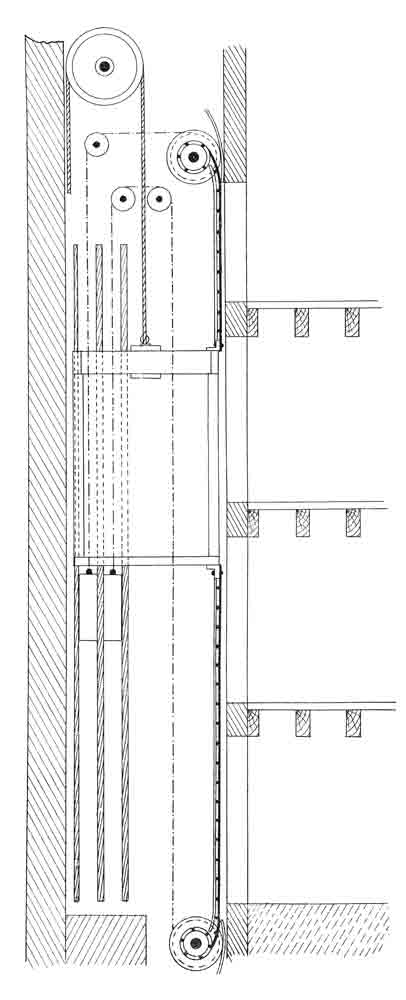

Lloyd & Hopkinson’s Safety Doors employed a simple system of levers that prevented the car from moving when the doors were open. The levers were attached to the doors such that when the doors were open and perpendicular to the cage, the levers were located immediately above and below the cage on two sides, effectively blocking the cage’s movement. Botterill’s Automatic Hoist Gate employed a large curved cam on one side of the cage that engaged a lever that raised and lowered a vertically sliding gate. Botterill’s Patent Flexible Hoist Guard consisted of two screens made of a “flexible material, such as sail cloth, woven wire, or asbestos fire proof material.” The screens were attached to rollers at the top and bottom of the shaft and to the top and bottom of the hoist cage: as it traveled through the shaft, the cage pulled the screens up and down, thus blocking all shaft openings except the one at which the cage was stopped.

Rigby & Taylor’s Automatic Hoist door also relied on a cam system, which in this case automatically opened and closed a pair of hinged shaft doors. Smith’s accounts of Lloyd & Hopkinson’s and Rigby & Taylor’s systems clearly state that because these systems relied solely on the action of the cams for their operation, the doors opened and closed every time the cage passed a given floor (regardless of whether the cage actually stopped). In both cases, this resulted in “considerable wear and tear” on the doors; he also noted that these systems required significant “additional power to drive the mechanism.”

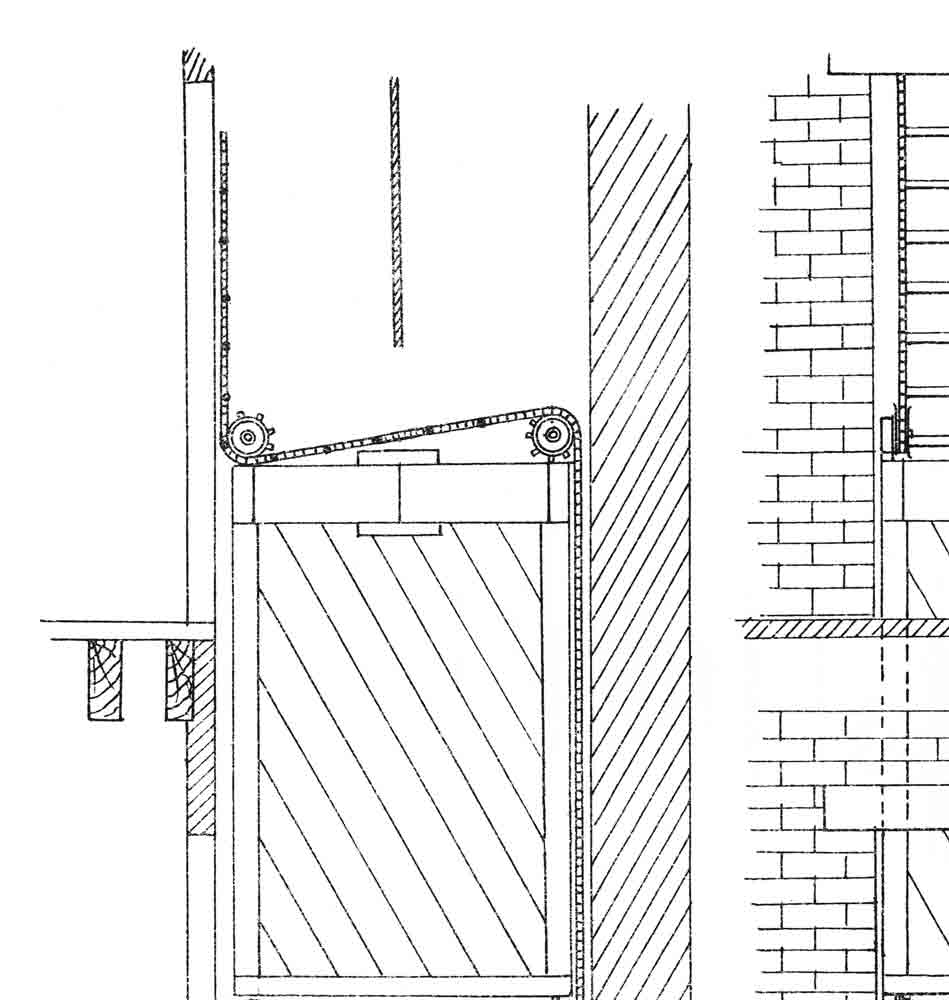

The eclectic group of inventors discussed thus far was joined by an equally interesting group of lift, hoist and crane manufacturers. Higginbottom’s Automatic Locking Gate had been invented and patented by Lloyd Higginbottom (1850-1923). He was a founder and partner in Higginbottom & Mannock of Manchester, a well-known hoist and crane manufacturer. This system consisted of a vertically sliding counterweighted door released and locked by a lever linked to a cam moved by a “small truck wheel” attached to the side of the cage.

Barker’s Automatic Locking Gate had been designed and patented by John Barker & Sons Ltd., owner of the Park Street Iron Works in Oldham, which had manufactured hoists and cranes since the 1870s. This gate was similar to Higginbottom’s in its basic operation, with a key difference being that the movement of the counterweight and gate were controlled by individual cam-driven mechanisms. Smith characterized this system as “simple in construction, and with ordinary care the locking mechanism should not get out of order.”

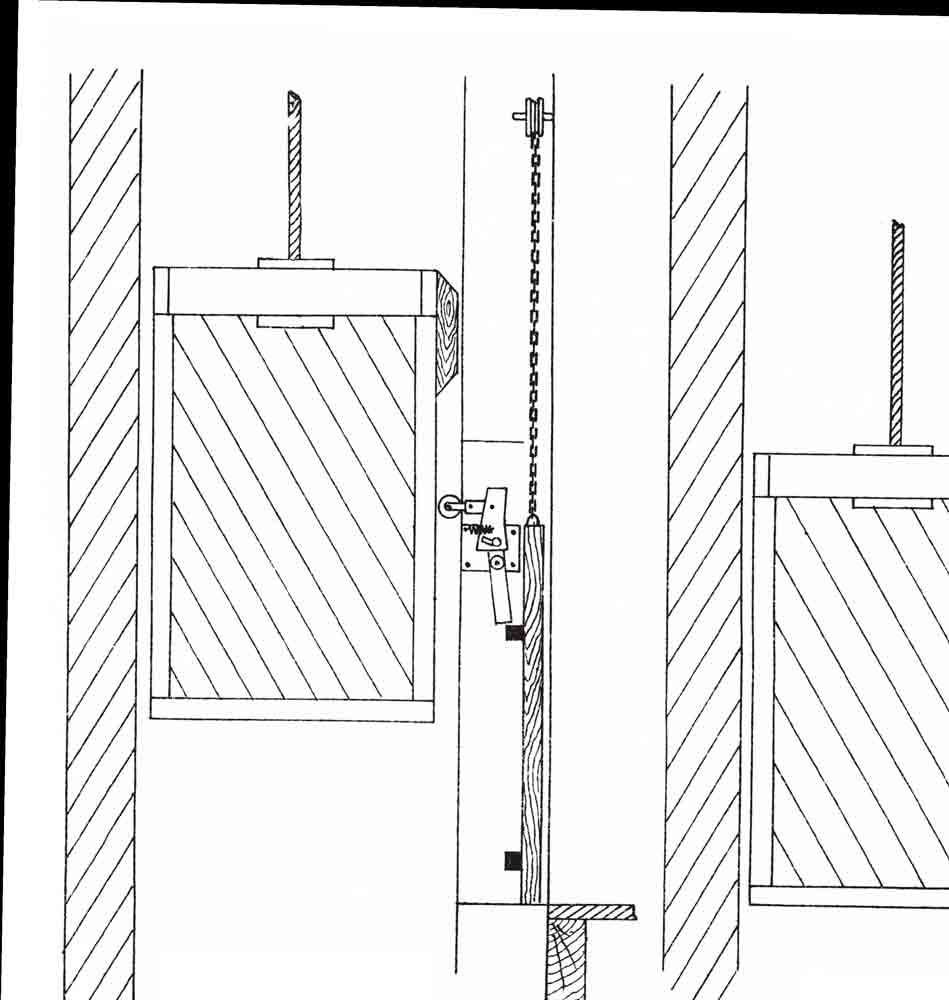

Newsome’s Automatic Hoist Guard, designed and patented by M. Newsome, Sons and Speddings, owners and operators of the Anchor Foundry in Dewsbury, was similar in its operation to Botterill’s Patent Flexible Hoist Guard. The key difference was that, in place of Botterill’s flexible screen, Newsome employed two large chains that extended the full length of the shaft; at each floor opening, a series of closely spaced metal tubes spanned between the chains and barred access to the shaft. The chain was designed such that, as the cage traveled through the shaft, the chains and metal tubes passed around and over the top, back and bottom of the cage. Smith noted that although this system was “an effective guard,” its disadvantages included the “considerable power” required to operate the hoist and the fact that the “noise caused by the passage of the links and tubes round the pulleys of the cage is great.”

Etchell’s Automatic Doors had been designed and patented by John C. Etchells, who had a lengthy career in the British lift industry. This system employed a mechanism below the landing floor that automatically raised and lowered “bolts” that held the doors closed when the cage was not present. When the hoist arrived at the landing, a cam attached to the cage activated the mechanism and unlocked the doors. Smith had observed, “When the mechanism is fixed below the door. . . unless care is taken, the bolts and catches are liable to become jammed and rendered inoperative by dirt and sweepings.”

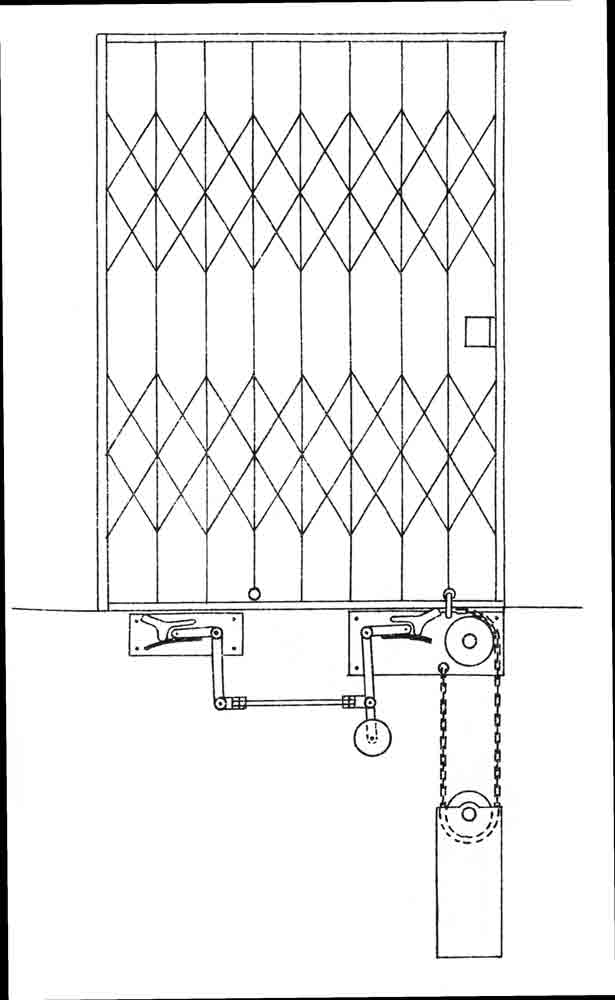

Waygood’s Automatic Safety Doors were produced by one of the best-known British lift manufacturers: R. Waygood & Co. This system employed a truck wheel on the cage that acted on a cam plate that released the door, which was automatically raised through the action of its counterweight. When the door was up, it was also prevented from descending until the cage had moved away from the landing by the locking mechanism. Finally, although not a lift manufacturer, Bostwick Gate & Shutter Co., builder of the Bostwick Collapsible Gate (available with and without an “automatic gear” system) was well known to industry members and lift users. The hand-operated Bostwick patent collapsible gate (invented in the 1880s) was a familiar feature on passenger and freight lifts throughout Great Britain. The automatic locking gear was located below the landing floor and operated in a similar fashion to Etchell’s system.

Part three of this article will conclude this investigation into Smith’s 1904 report with an examination of the additional safety mechanisms he described, as well as a brief look at the reported causes of hoist accidents and Smith’s recommended solutions.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.