How OSHA and the Arbitrary Enforcement of U.S. Government Laws Affect Us All

Oct 1, 2012

Observations on the American legal system and OSHA’s attempt to surplant elevator codes

In 1925, Franz Kafka published his well-known work, The Trial. The book described a successful professional man arrested and prosecuted by an inaccessible, detached government agency, for a crime entirely unknown to him. As the farce of his prosecution unfolds, neither the man nor reader learns the nature of the alleged crime. In Kafka’s world, the entire absurd process endured by the man illustrates that the “law” has nothing to do with any concept of “justice.” Instead, in The Trial, the law appears to be nothing but the brute force of government being wielded against a helpless and confused man – an impenetrable bureaucracy arbitrarily defining the law and, without explanation or notice, using it to swallow and destroy an individual.

For much of U.S. history, such a concept of the law appeared ridiculous. Indeed, the term “Kafkaesque” was coined to describe something that was illogical or senseless, like the events befalling the hapless man in The Trial. Few would believe that such a travesty of justice could never happen in the country. After all, America’s founding fathers predicated the country’s entire system of government on the concept of “inalienable rights” grounded in natural law – laws neither created by nor dependent upon man, but universal and emanating from a supreme creator.

Concerned that select people would place themselves above the law, or enforce it arbitrarily or to their own advantage, John Adams wrote that the republic must be a “government of laws, not of men,” (Massachusetts Constitution, 1780). To ensure this, the U.S. Constitution limited federal government power and instituted such things as a House of Representatives and Senate in Congress and the separation of powers between the president, Congress and courts. These checks and balances were aimed at preventing groups from using or abusing laws to oppress the individual. In short, the founding fathers were trying to avoid the kind of legal system depicted by Kafka in The Trial.

Unfortunately, it is uncanny how concepts thought impossible or fantastic in literature 100 years ago have become reality. From Jules Verne’s globetrotting electric submarine in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1870) to the biological warfare of H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds (1898), civilization’s progress, for better or worse, has consistently turned fantasy into reality. And so it is that, each day across the U.S., state and federal governments increasingly treat individuals and businesses like the poor, confused central character in The Trial. From selective application of the laws to arbitrary enforcement and interpretation of them, government increasingly sends the message that favored groups will prosper under the law, while disfavored groups will suffer.

Philosopher Ayn Rand once despaired that the time was approaching when the U.S. reached “the ultimate inversion: the stage when the government is free to do anything it pleases, while the citizens may act only by permission.” That time, assuredly, is behind us. To prove this, in 2009, lawyer Harvey Silverglate published Three Felonies A Day: How the Feds Target the Innocent. There, Silverglate chillingly described a country where the average person wakes up, goes to work, comes home and goes to bed, entirely oblivious he or she probably committed multiple federal felonies that day. Because federal agencies have been given free rein to pass countless laws, with incredibly broad and vague language, a federal prosecutor can bring charges against any citizen at any time for entirely ordinary behavior. After all, ignorance of the law is no excuse. No one is able to know all the federal laws that exist at any one time, not to mention countless state and local statutes, regulations and ordinances. This is handy knowledge when particular groups or individuals become disfavored by the people running the government.

This unfettered power is not limited to such high-profile federal agencies as the U.S. Department of Justice or Department of Treasury. OSHA, as well as its counterparts in state-plan states, is well aware of its power to reward favored constituents and punish disfavored employers and groups. Take the U.S. Postal Service (USPS), for example. A search on the OSHA database using the term “postal” shows that, from January 2009 to August 2012, at least 800 inspections of the USPS occurred. And those are just inspections considered “closed.” More than 143 results return for inspections still categorized as “open.” Even assuming a few establishments show up that are not USPS but happen to have the word “postal” in their name, this is nearly 1,000 inspections in about 3-1/2 years.

How could one establishment be hit that many times in such a short period? The answer is simple: overwhelmingly, the OSHA database shows that it inspected the USPS repeatedly because of complaints filed by the postal workers’ union. Thus, despite the fact USPS is insolvent and struggling to survive, its employees’ union has used OSHA to bludgeon it with inspections resulting in millions of U.S. dollars in fines over the last few years. Rather than see any ulterior motivation in the nearly 1,000 complaints submitted by the union and respond to such complaints accordingly (which can result in a letter inquiry to the employer, for example, instead of a full-blown site visit), OSHA continues to doggedly pursue USPS, find violations and issue huge fines. Coincidence? Hardly. The current OSHA, not to mention the Department of Labor (DOL), leadership has deep ties to organized labor, making unions one of the “favored groups” at OSHA and the DOL.

Moreover, OSHA is frequently attempting to enforce vaguely or generally written laws to require behavior that the plain language of its regulations does not require and, in many instances, companies have no notice would be required. One way it does this is through section 5(a)(1) of the act, known as the General Duty Clause. That section is the “catch-all provision” of the Occupational Safety and Health Act, intended to cover working conditions that are, or should be, known as dangerous but that do not fall under a specific regulation. It says that “[e]ach employer shall furnish to each of his employees employment and a place of employment which are free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm to his employees.” Recently, however, OSHA has used that section much more aggressively, using it to justify citations to employers for acts ranging from workplace violence caused by non-employees to injuries caused by an orca at iconic amusement parks to stampedes of unruly customers trying to take advantage of a Black Friday sale. The fact that millions of children may no longer be able to enjoy enthralling tricks by beautiful marine mammals at the sea park or be able to get a video-game console for Christmas that is otherwise unaffordable means little to the government agency deciding the General Duty Clause prohibits the activities that make those things possible.

The elevator industry has not been immune from OSHA’s attempts to enforce vague, generally written laws to require measures never before contemplated. The electrical safe work practices standards, such as those at 29 CFR 1910.335, say nothing about what type of personal protective equipment is required, other than that it would be “appropriate” for the work performed. Nonetheless, OSHA has cited several elevator maintenance companies for failing to follow the express provisions of a non-binding, voluntary industry standard called NFPA 70E. The actual legal requirement contained in 1910.335 says nothing about following NFPA 70E. Regardless, OSHA has insisted that following the non-binding voluntary standard is, effectively, the only way to comply with its laws.

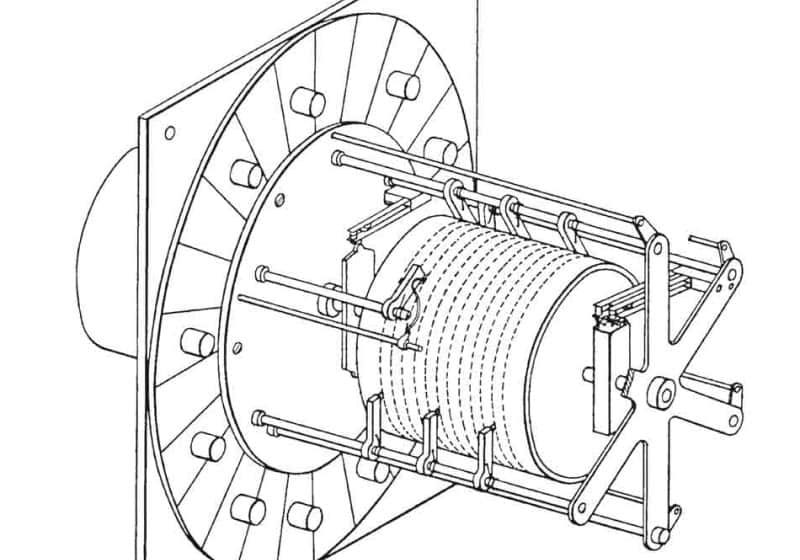

The guarding of equipment in machine rooms is another area OSHA is increasingly trying to usurp unto itself. Local jurisdictions have extensive regulations encompassed by, for example, the versions of ANSI A17.1 or A17.2 they have adopted that govern guarding requirements on elevator equipment in machine rooms. Despite this fact, OSHA has repeatedly attempted to use its very generally worded machine-guarding standards (like 29 CFR 1910.219) to require guards on machine-room equipment, even when no guards are required by the elevator codes that apply to that equipment. OSHA has also attempted to use the General Duty Clause to require guards on equipment like older drive machines. Without needing to go through any of the procedures designed to ensure building owners and elevator service companies have a chance to provide input into the process, as the local agencies charged with inspecting elevators would, OSHA would create, or make retroactive, guarding requirements in machine rooms. The fact this use of generally worded laws, should it be accepted, would impose millions of U.S. dollars in costs on building owners nationwide is of no concern to OSHA. OSHA only needs to consider such a thing when it actually engages in the rulemaking process, which is the proper way to impose new regulatory requirements.

Unfortunately, the laws and the current way government enforces them have clearly proven Kafka to be a realist. As Ayn Rand said:

“The only power any government has is the power to crack down on criminals. Well, when there aren’t enough criminals, one makes them. One declares so many things to be a crime that it becomes impossible for men to live without breaking laws. . . pass the kind of laws that can neither be observed nor enforced nor objectively interpreted, and you create a nation of lawbreakers.” The good news is, the government’s increasing use of the law in both selective and arbitrary fashions has not gone unnoticed by the people regulated by those laws. The more people become aware of their government’s abuse of the law, the more likely they will once again place limits on the power of the abusers.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.