Let There Be Light

Jun 1, 2015

The evolution of Columbia’s elevator light curtain

Virtually everyone who has ridden an elevator over the past several decades knows the feeling of his or her person, children, pets and/or possessions being annoyingly bumped by an automatic door that withdraws upon contact by the mechanical shoe, or buffer, at the door’s edge. Many people take advantage of the way these work by using them to hold the car for delayed passengers or to load/unload belongings on a particular floor, inconveniencing others up and down the line.

Columbia is not in the edge-selling business, but rather in that of edge design, development and manufacturing.

Developed with the advent of automatic elevator doors, these mechanical door edges were designed to help prevent injury to slow-moving passengers as they entered and exited the car and to help avoid litigation from possible harm caused by doors as they closed. While they largely fulfilled their intended purpose, they were not without limitations and problems. These systems relied entirely on direct contact, while the doors, which were quite heavy, were often slow to stop and change direction. Injury, property damage and litigation were vastly reduced but not entirely eliminated. Equipment failure due to constant, rugged use and abuse was not uncommon. An alternative method of presence detection needed to be found, avoiding direct contact and its inherent problems.

An early approach was the addition of so-called “electric eyes” — one- or two-beam systems that shot light across the opening a few inches above the floor — that worked along with the mechanical door edge to help eliminate direct contact with doorway obstructions. These did help catch many obstructions, but, since they did not protect the entire opening, the requirement remained for direct contact with the mechanical edge to protect the balance of the opening.

“The modern solution is light curtains,” says L.J. Blaiotta, president of Columbia Elevator Products Co. Inc., continuing:

“Light curtains are a much more certain and safe way to detect a presence, since they entirely eliminate physical contact and instead function by reacting to unbroken/broken beams of infrared light across the pathway of the elevator door. This technology enables passengers to enter and exit the car at their own chosen speed, within limits, while keeping the doors open as long as the beams remain intercepted. Should passengers take an excessive amount of time, however, a buzzer or other signal can be included to encourage passengers to move in or out of the elevator. The system can also be equipped to regulate the speed of the doors and the pressure with which they close. In addition to the safety and comfort they provide, light curtains, since they are much less mechanical, can significantly reduce ongoing maintenance time and costs and prolong the life of the elevator.”

As the benefits of light curtains became known to the elevator companies that were already coming to Columbia for architectural products, and as interest in mechanical edges began to fade, Columbia began to consider going into the business of including light curtains. Making only cabs and doors at the time, Columbia had been asking its OEM and independent customers which self-obtained retractable door edge or electric-eye system they would be using and, along with their orders, to provide a template indicating where holes needed to be positioned to easily accommodate subsequent installation in the field.

As awareness and demand for light curtains took hold, Columbia began receiving requests from convenience-seeking customers to ship its products with this newer technology already installed. At first, Columbia was not inclined to fulfill such requests, since, according to Blaiotta, “we were making only doors.” But, he explained:

“As we entered the door-operating business with our 2007 acquisition of Kansas-based Elevator Solutions, we began providing light curtains as part of the door-operator/light-curtain ‘mini-packages’ that our customers were increasingly requesting for a one-stop-shopping advantage. This was a natural progression for us, from offering only entrances and doors, to then adding cabs, then operators and, finally, light curtains, and made us into the only domestic independent manufacturer able to provide this architectural product configuration and service.”

Columbia’s first step into light curtains was with residential products, using its ALURE® operator product line. Why the initial start with residential rather than commercial? Blaiotta explains:

“Because the residential elevator companies fairly suddenly developed an immediate need. During their first several decades in the business, with no requirement to install power-operated doors, they had installed only doors that were manually operated. As the residential market increasingly began to demand ‘real elevators,’ these needed to have power-operated, fully automatic doors, such as those in commercial installations. The residential companies, however, had little if any knowledge about that end of the business. They had no experience with power-operated doors and were stymied by the tight physical tolerances required by the constrained space of the residential environment. Many literally did not know what to do and relied on us to recommend and provide the entire solution. As they purchased their doors and operators from us, they requested delivery with preinstalled edges, and we began to provide this service by bundling in light curtains that we obtained from third-party providers.”

Once on this path, it was inevitable that Columbia would begin receiving similar requests from its commercial customers, who favored this one-stop solution over having to obtain and assemble their doors, operators and light curtains from various sources. As demand increased, Columbia began thinking about directly providing light curtains, as Blaiotta explains:

“In keeping with Columbia’s general philosophy, we wanted to provide the ‘very best’ and evaluated a number of products then on the market. However, the ones we found were designed primarily as safety guards for industrial machinery and were not practically adaptable to our industry’s needs. These companies were very good at optics and sensing methodologies but had no idea how to install their technologies on elevator doors. The products weren’t ‘smart,’ and their complex arrays of features and benefits were all à la carte. For instance, if we wanted to install a light curtain in a wet environment, we had to buy a special edge that was waterproof. If we had low voltage in our cab, we had to buy a power supply that was low voltage. If we had only high voltage, we needed a different power supply. And, attaching these devices to elevator doors and strike jambs required the use of odd, flimsy mounting bracketry that made installing them extremely complicated. We then went about analyzing what was actually needed for American elevator light-curtain applications. Here, so to speak, we saw an opportunity to ‘design the better mousetrap.’”

Unlike foreign installations, U.S. elevator doors sit 2-plus in. back from the edge of the sill to accommodate the clutch assemblies on the backs of the doors. To serve the American market and address this gap, Columbia set about designing light curtain equipment that was “fat” enough to block prying young hands and visual access to the pickup rollers and clutches that enable the hoistway and car doors to interact. This was accomplished by designing the light curtain chassis in a way that screwed to the back of the hoistway sliding door, filling the gap, acting as a sort of sight guard or non-vision wing, and making the most favorable use of the space occupied in earlier days by mechanical edge equipment.

“In addition to the safety and comfort they provide, light curtains, since they are much less mechanical, can significantly reduce ongoing maintenance time and costs and prolong the life of the elevator.” – L.J. Blaiotta, president of Columbia

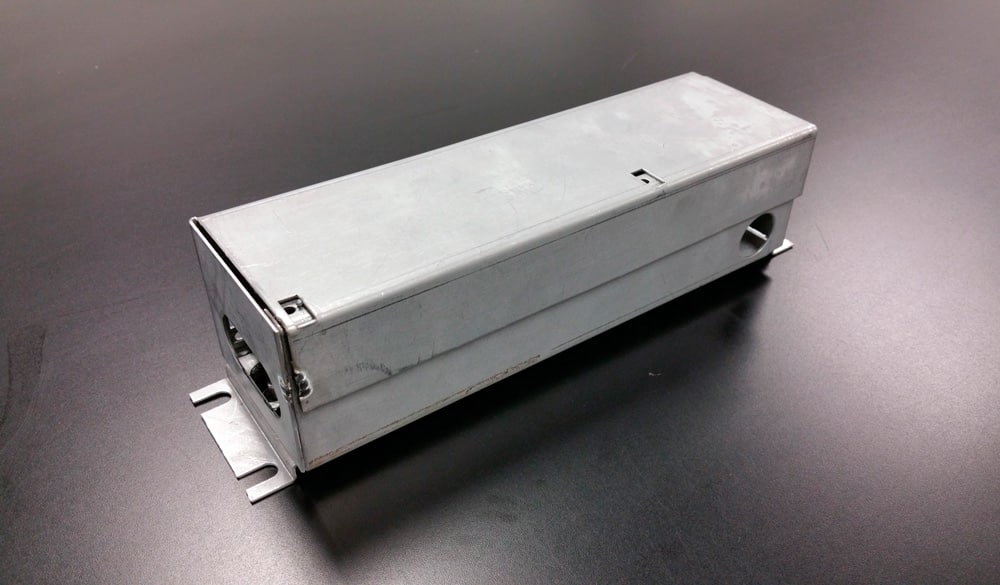

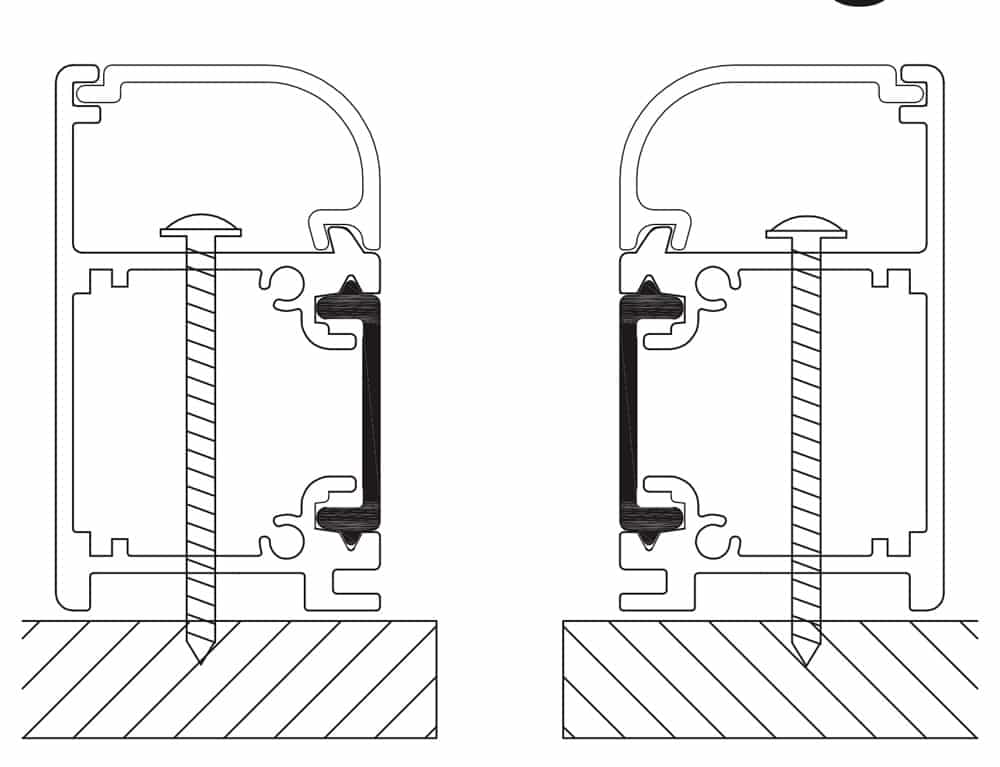

There were additional issues to address. For example, on center-opening pairs of doors where one is equipped with a transmitter that sends the beam, and the other with a receiver that catches it, the edges can be screwed to their respective doors in the same way. But, with a side-sliding door installation, the transmitter on the door is moving, while the receiver remains stationary on the strike jamb and the door closes against it. On the strike jamb, the equipment needs to be mounted in the same direction as the light beam, perpendicular to the surface of the jamb, while, on the door, it needs to be perpendicular to the light beam and door. This required a way to accommodate two different fastening directions. Rather than work with varying brackets for each, Columbia designed a single profile that works equally well in both applications. A bevel was added on the strike side of the holder to avoid possible injuries by sharp metal. Additionally, a removable cover was added to the entire assembly to hide the fasteners and discourage tampering. Every unit is also waterproof and designed to accommodate any environment and electrical requirement.

The result was Columbia’s LIFEGUARD™ light curtains, which are included in Columbia’s door/operator/light-curtain package. Today, according to Blaiotta, the company is not in the edge-selling business, but rather in that of edge design, development and manufacturing. To service other manufacturers wishing to order these edges in volume to supply to their own customers, Columbia has assigned exclusive global distribution rights to SCS Elevator Products Co. of Red Wing, Minnesota. According to SCS Business Development Manager Kevin Rippentrop, the company provides two distinct distribution programs: one for OEMs requiring volume and another for independent elevator companies.

Rippentrop explains:

“When we sell volume to an OEM, we’ll be told, for example, that it wants them all in 24-V configuration, and we’ll design the product specifically to work with the OEM’s power supply, door operator, etc. When, on the other hand, we sell to an independent, we make it universal so that it works with everybody’s product. The shape is the same in both cases, but the products are configured differently for each sector.”

Concludes Blaiotta:

“Our ‘better mousetrap’ quest has turned into a very popular solution, and we see demand for our mini-bundles growing rapidly. We’ve ended up with an ‘enlightened’ solution to this aspect of elevator safety: an easy-to-fasten, universal holder and a light curtain that is vandal-resistant, waterproof and multi-voltage, with self-diagnosing LEDs and 154 beams of infrared light for object detection. To the best of my knowledge, all this is unique to the industry.”

A section of Columbia’s LIFEGUARD Safety Edge, shown with its “Quik-Connector.” Dimensions are 3/4 in. wide, 1-1/4 in. deep and 80 in. long with a cable length of 144 in. Internal boards are waterproof.

LIFEGUARD’s power supplies can accommodate 24 VDC and 85-265 VAC.

LIFEGUARD’s power supplies can accommodate 24 VDC and 85-265 VAC.

Door Fixing

Strike Fixing

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.