Miller’s Patent Screw Hoisting Machine

Jan 1, 2021

Examining the companies and enigmas surrounding William Miller and the inventor’s wild marketing claims

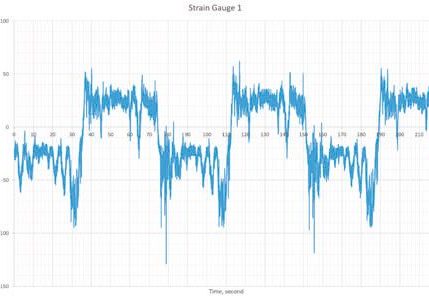

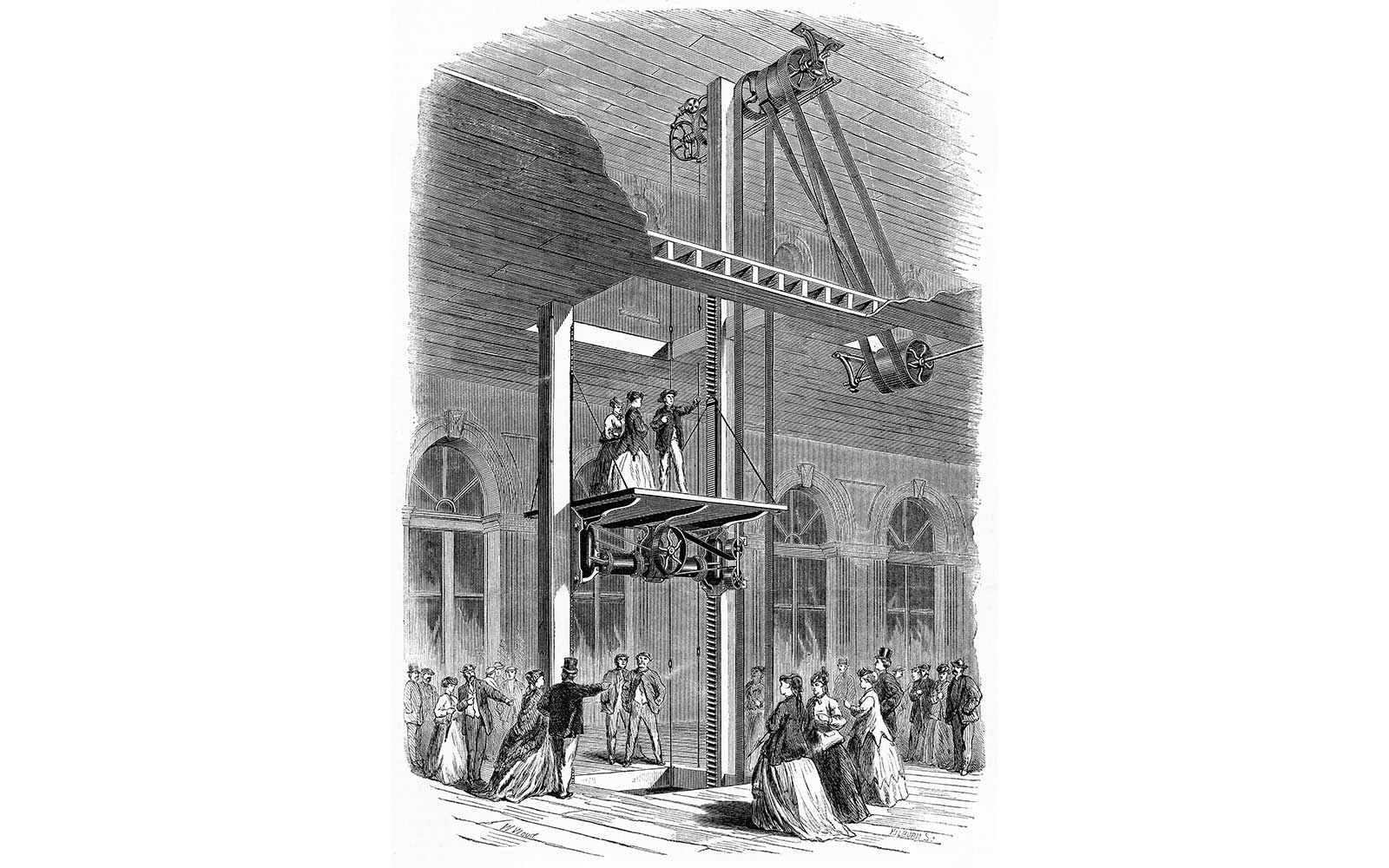

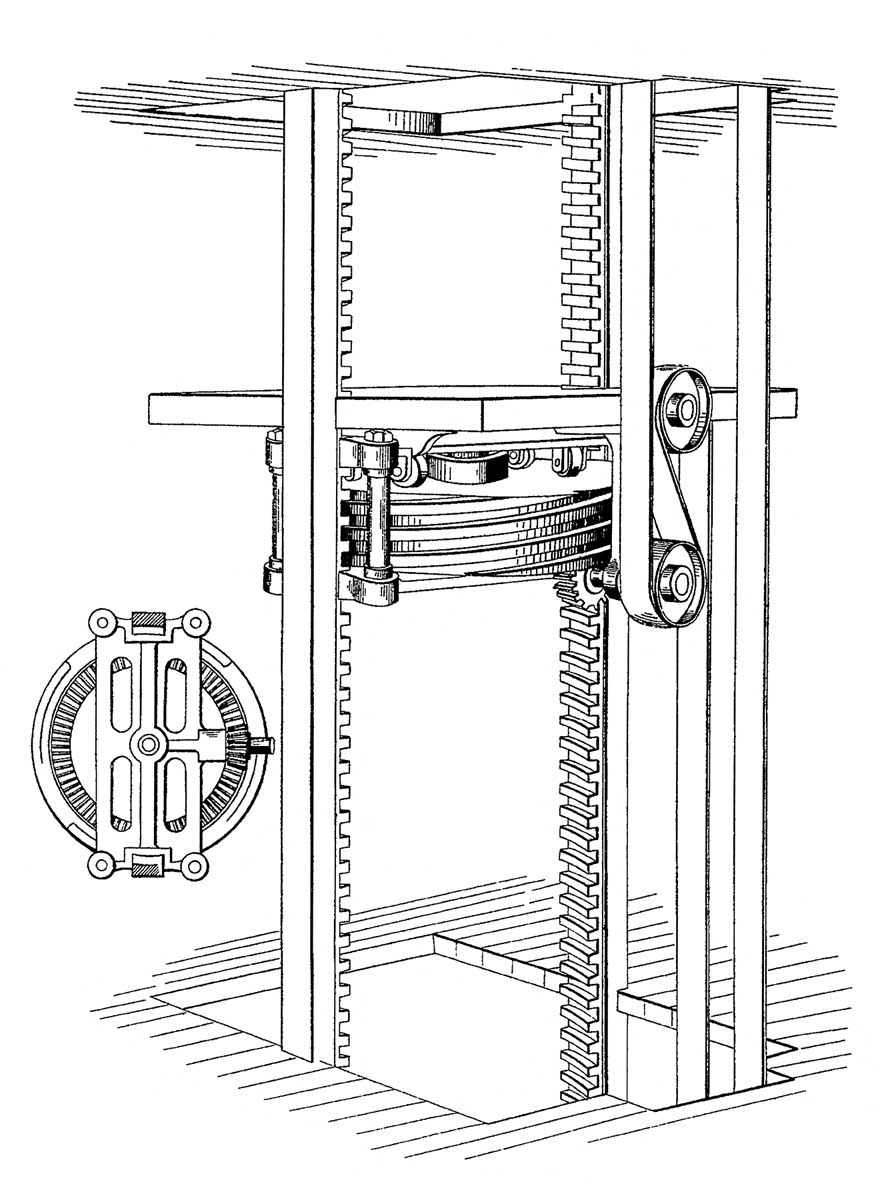

The November 16, 1867, issue of Scientific American included an illustrated article titled “Improvement in Hoisting Machinery.” The article examined an elevator designed by William Miller of Cincinnati and manufactured by Campbell, Whittier, & Co. of Boston. The article’s illustration was one of the earliest and most dramatic 19th-century depictions of a freight elevator published in the U.S. (Figure 1). The story of this image and the elevator it depicts represents a tale of one inventor, two companies and (in many aspects) an unsolved mystery.

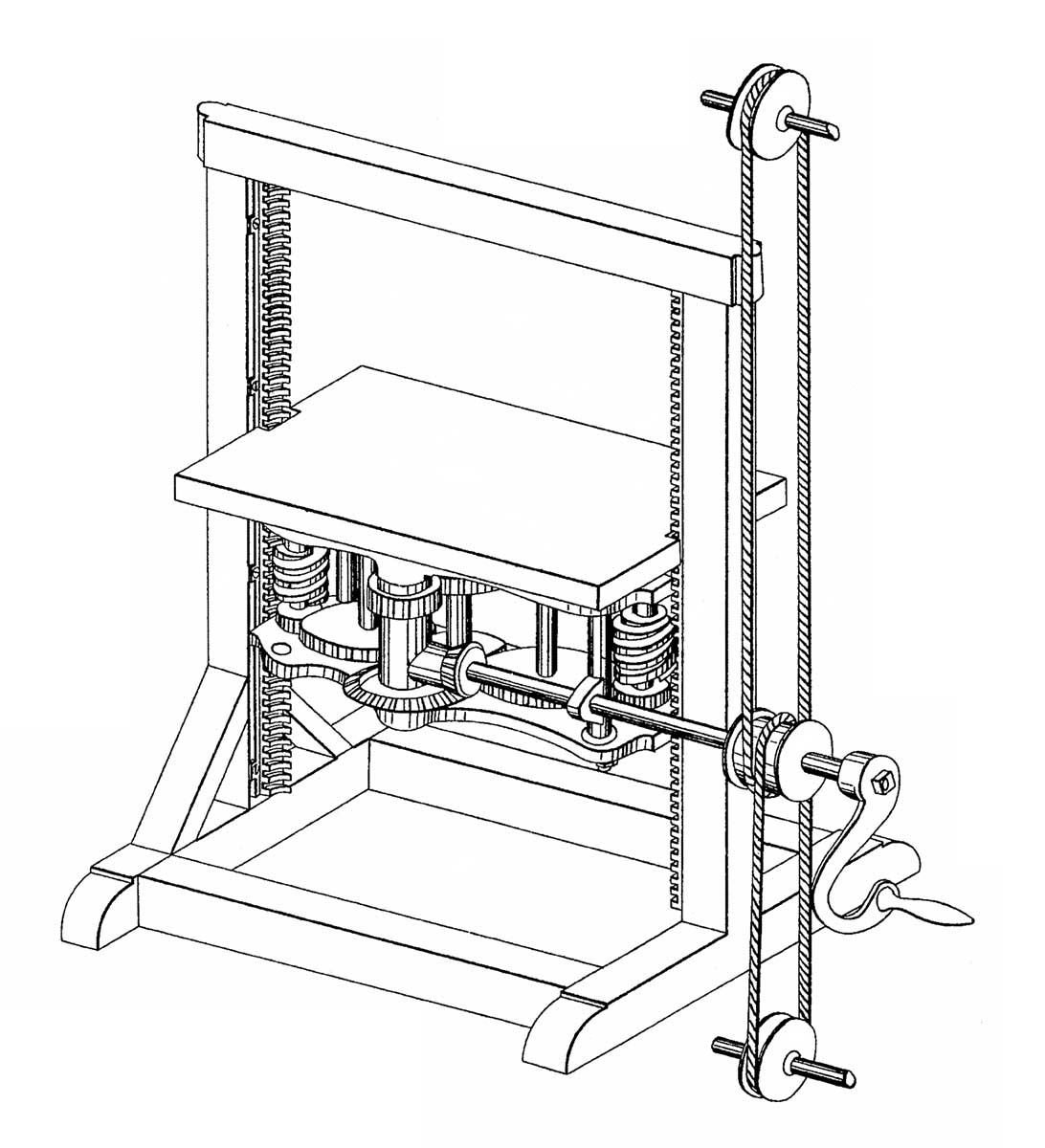

In May 1863, William Miller of Cincinnati was issued “Improvement in Hoisting Machines” (U.S. Patent No. 38,497). The design was the first to employ worm-gear drive system (Figure 2). Miller employed “worm-wheels” that meshed with vertical “worm-racks,” and he stated his system was “obviously better adapted to the purposes of a hoisting apparatus” than rack-and-pinion drives.[1] He claimed his design provided

“. . .additional security in the ability to use a worm-wheel of any desired number of threads, each one of which has a complete surface-bearing at right angles to the axis of the worm upon the threads of the worm-rack, whereas a pinion, being capable of bearing only by one or two cogs at a time, and in oblique directions, is liable either to strip or force apart the stanchions. . . . In order entirely to avoid such tendency to lateral displacement in my arrangement, it is only necessary to make the under surfaces of the worm-threads and the upper surfaces of the rack-threads perfectly horizontal in the planes of their axes.”[1]

Miller also claimed that, when stopped, the worm-wheels would hold:

“. . .the platform perfectly stationary. . . without the necessity of any special detaining mechanism, such as pawls or catches, which can act only by the partial descent of the platform and which, from their liability to derangement, often fail to act at the critical moment, and result in serious and fatal casualties.”[1]

The reference to the possible problems associated with the use of “pawls and catches” appears to be a criticism aimed directly at Otis Brothers & Co., the pawl and rachet safety device of which featured prominently its advertisements.

Why Miller felt it was necessary to include this observation in his patent text is this story’s first mystery. While the comparison to rack-and-pinion drives makes sense, his mention of the Otis safety seems to have been included solely as a means of attacking a rival manufacturer. In fact, in 1863, Otis Brothers was very much a fledgling company that had a limited market share and minimal national presence. Elisha Graves Otis had died in 1861, and, while he had maintained a modest elevator business throughout the 1850s, following his death, his sons (Charles and Norton) essentially had to rebuild the company, a task made more difficult by the start of the Civil War in April 1861. Miller’s awareness of Otis’ safety may have resulted from a familiarity with manufacturers in the eastern U.S. However, the precise nature and origin of this familiarity, particularly (as will be seen) with Campbell, Whittier, & Co., is unknown.

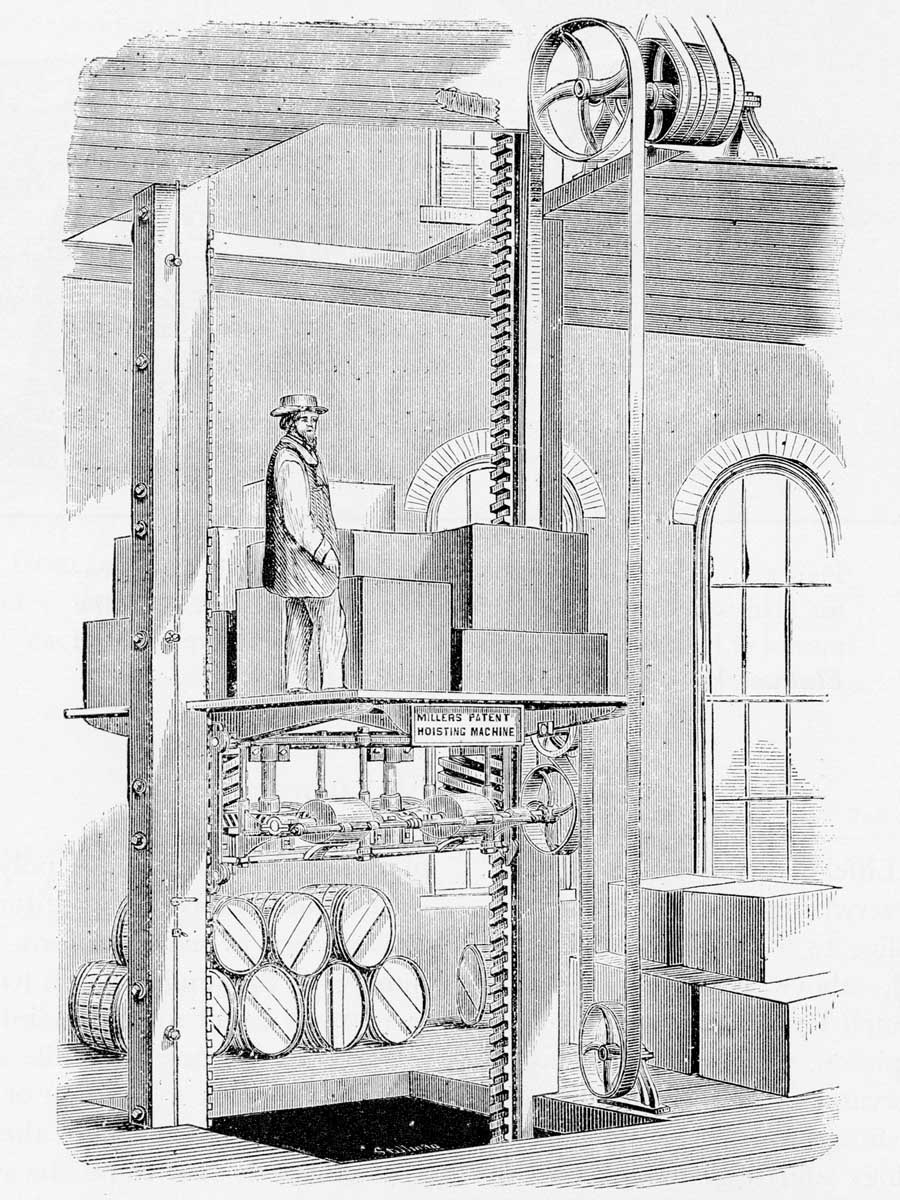

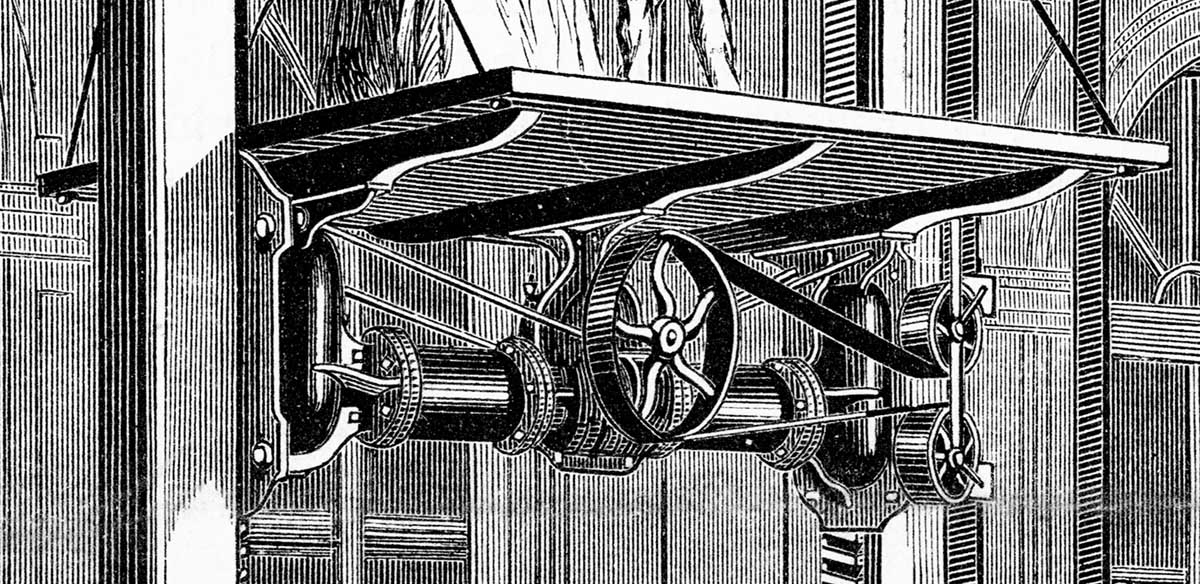

In 1864, Miller established William Miller & Co. in Cincinnati. The new business specialized in the manufacture of “hoisting machinery.”[2] The following year, Campbell, Whittier, & Co.’s advertisement in the Boston Directory proclaimed it was the “sole agents and manufacturers of Miller’s patent safety elevator for factories, stores, etc.”[3] Any doubt the “Miller” mentioned in their advertisement was William Miller is dispelled by an engraving featured in an illustrated promotional brochure produced by the company in 1865 or 1866 (Figure 3). The illustration clearly depicts the drive mechanism in Miller’s 1863 patent, here depicted powering a freight elevator in an industrial setting (compare Figures 2 and 3). The engraving’s inclusion of a belt-drive power-system derives from an 1865 patent in which Miller presented a modified version of his original design (Figure 4).[4]

The text that accompanied the 1865/1866 image modified Miller’s description of his worm-gear drive system, describing it, instead, as “Miller’s patent life and labor-saving screw hoisting machine” and claiming that “the screw is the only safe principle on which to construct a hoisting machine or elevator.”[5] This characterization of the system as a “screw hoist,” rather than a “worm-gear hoist,” was used for the remainder of its commercial life. The text also described the elevator as a “superior hoisting machine, designed for store and warehouse hoisting. It is very simple in its construction, compact, durable and not liable to get out of order.”[5]

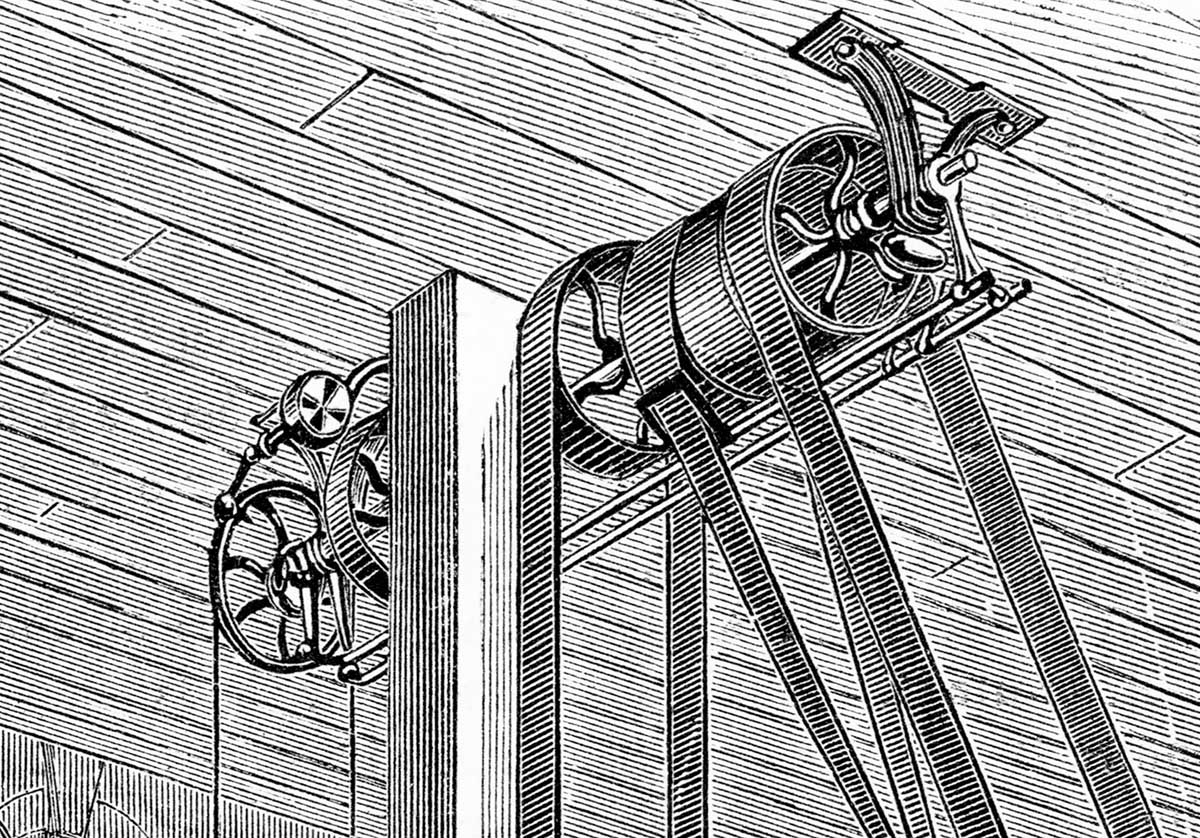

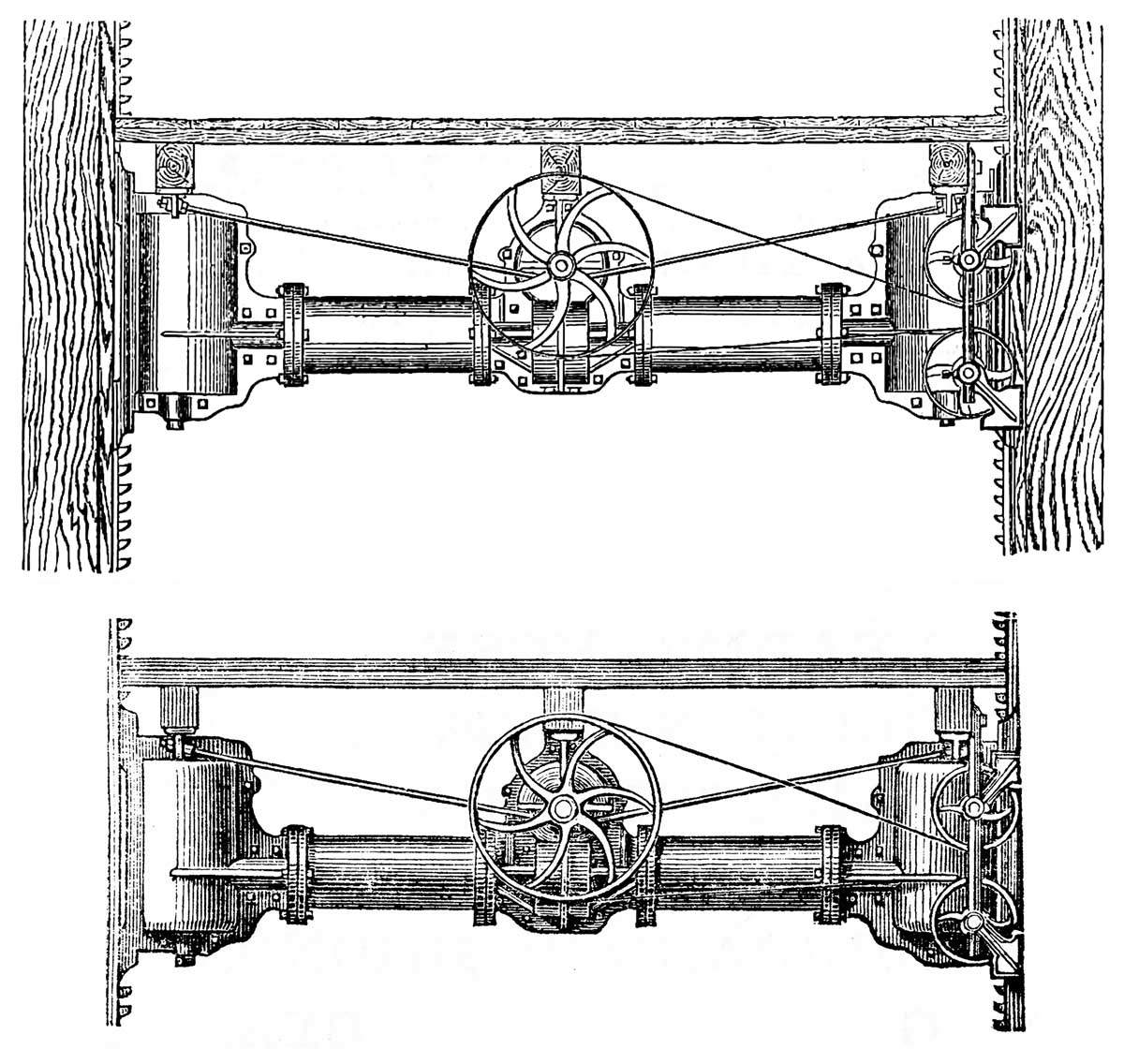

In addition to the production of the illustrated brochure, Campbell, Whittier, & Co. advertised its new elevator in city and state business directories throughout the Northeast from 1865 to 1867. The highlight of its advertising campaign was the publication of an illustrated article in the November 16, 1867, issue of Scientific American. A detailed examination of the article’s text and the remarkable accompanying image reveals the continued development of the elevator (compare Figure 1 to Figure 3). The drive system, which was now housed in an iron framework, was described as follows (Figure 5):

“The pulley in the center drives a worm screw, which, by means of a gear working into it and by miter gears, moves the two main screws on the sides that engage into the screw racks, which are firmly secured to the posts. Thus, the whole platform and gearing [move] up and down together, this being the only elevator in which the motive and sustaining power are inseparably connected with the platform.”[6]

Power was supplied to the elevator by a belt-drive system, which was composed of an “endless” belt connected to a belt-driven power supply (which was also driven by endless belts). This system followed the pattern used to power all industrial machinery during this period:

“An endless belt, running from top to bottom of the hatchway, gives motion to the center pulley, being passed under and over the smaller pulleys at the side. If this belt should break or come off, the platform remains stationary of itself. . . and is incapable of being moved up or down till power is again applied to the pulley.”[6]

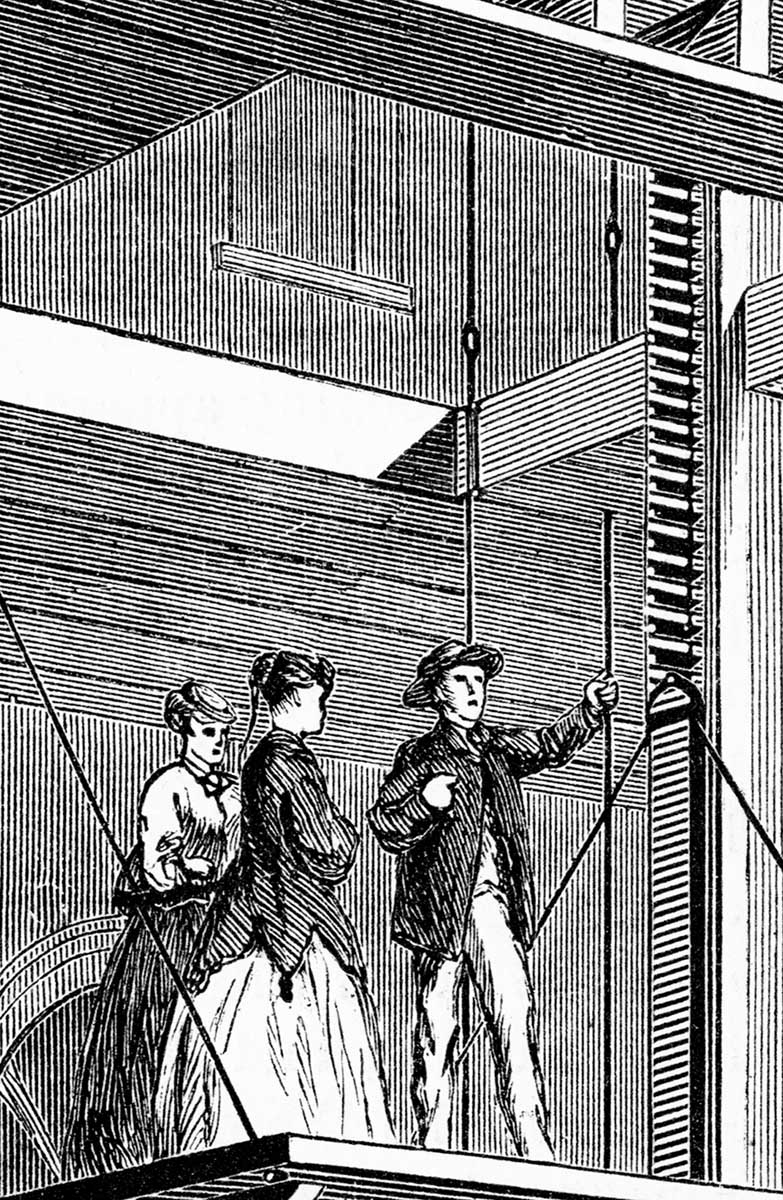

The elevator was controlled by a shipper rope, which operated a belt-shipper that moved the power-belts from loose to working pulleys (Figures 6 and 7). The system used on the elevator was:

“. . .an improved belt shipping apparatus. . . only the belt to be used at the time is moved on to the working pulley, thus saving wear and tear of belts. The brake for overcoming the momentum of the platform is applied by the same movement which ships the belt, so that the very instant the belt leaves the working pulley, the elevator stops.”[6]

The elevator’s description also claimed that it was equipped with a counterweight, “suspended over suitable sheaves by a wire rope,” which was equal to weight of the platform.[6] However, no such device is shown in the engraving, and, given the absence of side-posts and a cross beam, it’s difficult to imagine how the counterweight’s rope would have been attached to the platform. The article’s conclusion reiterated the system’s primary advantages:

“This machine cannot fall, it rises no higher than is desired and can be stopped within an inch of the intended spot. Its cost is no greater than that of first-class rope elevators, [and] it can be run at any speed by altering the size of the center pulley.”[6]

Campbell, Whittier, & Co. continued its advertising campaign for Miller’s elevator until 1870, after which no mention has been found. This campaign included advertising in city and state business directories, as well as newspapers. Many of the advertisements produced between 1867 and 1870 featured an engraving of the drive mechanism depicted in the 1867 Scientific American illustration (Figure 8). No evidence that speaks to why the company stopped promoting the elevator has been found. What is known is that it was never advertised in the Cincinnati area, and Miller never promoted himself as the designer of “Miller’s Patent Screw Hoisting Machine.”

Miller manufactured elevators in Cincinnati from 1864 to 1890. From 1864 to 1882, he operated as William Miller & Co., and in 1883, the company became the Miller Elevator Co. In the early 1880s, his advertisements noted that his company manufactured “Miller’s patent steam and hydraulic elevators, passenger and freight.”[9] This claim is interesting, because Miller had only three elevator patents to his name: two associated with his original worm-drive system (the rights to both of which were likely owned by Campbell, Whittier, & Co.) and a patent issued in 1867 for an improved safety device.[10] The safety device was a version of a rachet-and-pawl system similar to the well known Otis safety. The fact that no claim of his building “patent” elevators appeared until 1882 suggests he pursued additional patents in the 1870s or that he had acquired, purchased or been assigned patent rights to new systems. Regrettably, no evidence has been found that explains this speculation; thus, this constitutes yet a final mystery.

Campbell, Whittier, & Co. appear to have first entered the emerging elevator market in 1864, in large part through the acquisition of Miller’s patent and development of his Elevator. In turn, it’s reasonable to assume that the sale of his rights provided Miller with the capital needed to establish his elevator company. In Boston, this beginning eventually led to the creation of the Whittier Machine Co., which became a leading regional elevator manufacturer by the end of the 19th century. In Cincinnati, this beginning provided William Miller the opportunity to pursue a 26-year career as a successful local elevator builder. Both trajectories were made possible by the power of invention and the possibilities perceived by pioneers of the nascent vertical-transportation industry in the mid-19th century.

References

[1] William Miller. “Improvement in Hoisting Machines,” U.S. Patent No.38,497 (May 12, 1863).

[2] William’s Cincinnati Directory, Cincinnati: Williams & Co. (1864).

[3] Boston Directory, Boston: Adams, Simpson, & Co. (1865).

[4] William Miller. “Improvement in Hoisting Machines,” U.S. Pa 48,579 (July 4, 1865).

[5] Campbell, Whittier, & Co. Advertising Brochure (1865/1866).

[6] Scientific American. “Improvement in Hoisting Machinery”(November 16, 1867).

[7] Massachusetts Register, Boston: Sampson, Davenport & Co. (1867).

[8] Manufacturer and Builder. Campbell, Whittier, & Co. advertise (January 1869).

[9] William’s Cincinnati Directory, Cincinnati: Williams & Co. (1882).

[10]William Miller. “Improvement in Hoisting Machine, U.S. Patent N 64,785 (May 14, 1867).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.