A challenging modernization job in California drove a group of elevator professionals, engineers and architects to think outside the box to get the job done.

Modernizing the clock-tower elevator at the 1920s Santa Barbara County Courthouse in Santa Barbara, California, sounded simple on the surface but ended up being so complex that its principals doubted at first it could be done. It involved raising the system’s top landing by 10 ft. to provide greater access to the courthouse’s observation deck and sweeping vistas. The elevator was originally intended to transport a clock master up to the clockworks, not to transport a steady stream of visitors to the observation deck. But, over the years, its purpose shifted as the structure increased in popularity. The previous elevator stopped before it reached the deck, and visitors had to take stairs the rest of the way. That made the deck out of reach for many people with physical disabilities.

The job came with myriad caveats: adhering to a tight schedule, working in confined space, preserving the system’s original outward appearance and taking care to not damage a fragile building “where every part of the hoistway seemed to fall apart when you touched it,” recounts Michael Shaw, Operations manager at Republic Elevator Co., who oversaw concept and design.

Thanks to the expertise, cooperation and determination of those involved, he says, the project was completed to specifications and in time for its grand debut at Santa Barbara’s annual Old Spanish Days Fiesta in August 2015. “It was no easy task to complete this modernization,” Shaw observes. “There was extremely important coordination among many trades . . . simultaneously involved in getting everything accomplished in an orderly and precise fashion.”

Working for the County of Santa Barbara, architect Robert Ooley, FAIA, and general contractor Vernon Edwards Constructors, Inc. reached out in March 2015 to Shaw and engineer Juan Pablo Salguero of Vertical Fusion LLC in Weston, Florida. Shaw said he first pitched to Salguero the idea of using machine-room-less (MRL) technology. Shaw recalls:

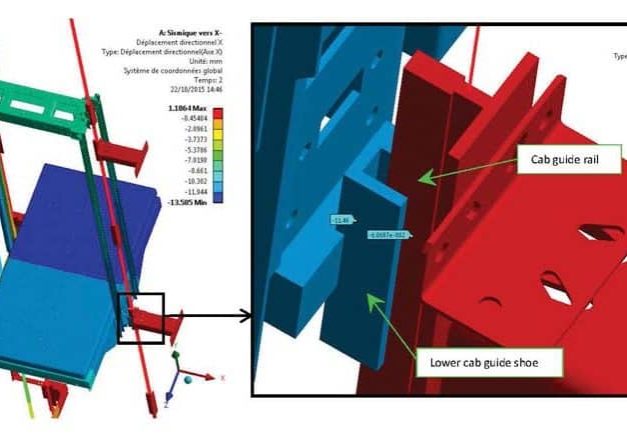

“I figured if we reroped the car two to one and utilized 3/8-in. hoist ropes, they would be able to reduce the size of the overhead sheaves, lower the top of the car profile and provide sufficient overhead.”

But 16 ft. of available overhead could accommodate neither an MRL system nor existing equipment. (The original plan was to raise the original equipment 10 ft.) “We had to fit a lot of stuff into a rather small, tight space,” Shaw recalls.

A turning point came when Shaw contacted Doug Witham of GAL Manufacturing Corp. Witham was on the West Coast for business at the time, and drove up to Santa Barbara to take a look at the project and meet with Shaw, city officials and Vernon President/CEO Todd Edwards. Shaw recalls:

“After [Witham] crawled all over the project, top to bottom, he committed GAL and Hollister-Whitney to providing, in short order, the motor, controller and all other equipment required for the project. If it were not for [Witham] and all of the help and assistance from everybody at GAL/Hollister-Whitney, this project would never have been successfully delivered in such a limited timeframe.”

The challenges facing the team extended beyond the tiny space in which they had to work: the vulnerable building had to be handled with extreme care. Shaw says intense engineering and architectural work was required before anything could be moved or built. He states: “You do not rip open a 90-year-old building and expect to not uncover all kinds of unruly unknowns when you open up the walls.”

Numerous steps were required, each presenting its own set of complications and challenges. They included:

- Engineering a new overhead sheave assembly and installing it before the old elevator could be removed

- Removing the top entrance

- Enclosing the old entrance and patching it to match the existing exterior

- Cutting a new entrance

- Installing a working platform atop the car to allow a new remote reset governor to be serviced

A “Grand” Architectural Showpiece

Replacing a smaller building at the same location completed in 1888, the sprawling courthouse at 1100 Anacapa Street in downtown Santa Barbara is composed of four buildings totaling 150,000 sq. ft. It was designed by William Mooser III in the Spanish Colonial Revival style and is made of stucco, terra cotta, metal, wood, stone, ceramic tile and glass. Architect Charles William Moore called it the “grandest Spanish Colonial Revival structure ever built.”

The structure is a California Historic Landmark, on the U.S. Register of Historic Places and is a U.S. National Historic Landmark. Landscaped with nearly 60 varieties of native palms, along with other trees, shrubs, climbing vines and flowers, its sunken garden is a popular event venue. The courthouse welcomed nearly 7,000 visitors from 60 countries in 2014.[1]

A major highlight of the courthouse is the clock tower known as El Mirador, Spanish for “The Looker.” It is an apt name, since the deck affords 360° views of the lush, verdant countryside from a 111-ft. vantage point. Photographs on the deck describe the various sights one is looking at in the area that has come to be known as the “American Riviera.”

Site’s Significance Drives Precision

The significance of the site was not lost on the elevator-modernization team. At times, employees’ work resembled that of a sculptor or surgeon. Vernon laborers gingerly carried or hoisted heavy equipment and bags of concrete up the long hoistway, and delicately chipped away at interior concrete walls to maintain sufficient running clearances for the counterweight. Shaw elaborates:

“The professional work provided by Vernon Edwards Constructors was the backbone of this entire project. Todd Edwards personally kept his fingers on the pulse of the project every step of the way to ensure first-rate work. Project Superintendent Mark Hilden went far beyond what would have been expected of him in that role, whether it was making himself available at any time, designing structural components or physically helping move hundreds of bags of concrete up the final set of stairs to the deck to help the laborers.”

Outstanding performances were given by all involved, Shaw observes. Architect Ooley, he states, was instrumental in completing the project on time. Shaw adds:

“With every new development, [Ooley] calmly wrapped his head around the challenge and came with either a new course of action or answer to keep the job steadily moving forward. There were so many hurdles to surmount, it was truly amazing to simply complete the project on time.”

About Salguero, he says:

“From the onset of the design concept, [Salguero] was able to understand completely what had to be accomplished and was instantly able to handle tasks in an amazingly quick manner. He not only generated drawings overnight, he managed to finish all of the mechanical engineering drawings and, once approved, managed to get the overhead sheave assembly, counterweight sheave assembly, car-top sheaves and motor pedestal all manufactured and delivered in time. His engineering expertise and calm demeanor convinced the entire team this project was doable in the timeframe allotted. He made numerous trips between Florida and Santa Barbara to ensure every aspect of the project was spot-on correct.”

Aside from now traveling all the way to the observation deck, the elevator and its environs look almost identical to the one that was there before, as per county requirements. It traverses the basement and three floors, has a capacity of 3200 lb. and travels at 200 fpm. But the new system is safer, more efficient, modern and easier to maintain. Such behind-the-scenes, yet important, new features include a fire-control system with new heat detectors for all floors and for the machine room; ELSCO and counterweight roller guides; GAL MOVFR door operator with an encoderless variable-voltage, variable-frequency drive; door tracks, hangars, pick-up rollers and interlocks; buttons and key switches; Sabbath operation; an earthquake-monitoring device; and a strip drain (custom designed by Shaw) for the new top landing to prevent rainwater from entering the hoistway.

Additional people involved include Jef Dell, president of Republic Elevator; Republic Lead Mechanic Mike Kuhm; and project consultant John Ireland of Scott Elevator Consulting.

All look back on the project with pride. “Now it looks like it did before, but it sure runs like a new elevator,” Shaw states. “And now, everyone, mobility challenged or not, can access the stunning views from the historic clock tower.”

Reference

[1] Stevens, Kay. “New Courthouse Docents,” Santa Barbara Independent, April 7, 2015.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.