Requirements for Lift Guarding

Feb 22, 2022

A look at prescriptive detail of the regulation and guidance for guarding in light of the case law.

recent Linkedin post advocating the use of quick-release fixings for a lift machine sheave guard, coupled with my day-to-day observations of guarding installed to lifts, made me think that a short reflection on the requirements for lift guarding might be appropriate.

Looking first at U.K. primary legislation in the Health & Safety at Work Act (HSWA) 1974, Sections 2, 3, 4 and 7 of the Act place duties on employers in relation to the safety of their employees and to the safety of persons other than employees; and on persons concerned with premises in relation to the safety of persons other than employees; and on employees themselves.

Section 6(1)(a) places a duty on designers, manufacturers and suppliers of equipment “to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, that the article is so designed and constructed that it will be safe and without risks to health at all times when it is being set, used, cleaned or maintained by a person at work.”

In terms of the state of the art requirements for fixed guarding, Regulation 1.4 of the Supply of Machinery (Safety) Regulations 2008 requires that:

“Guards and protective devices must:

- be of robust construction,

- be securely held in place,

- not give rise to any additional hazard,

- not be easy to bypass or render non-operational,

- be located at an adequate distance from the danger zone,

- cause minimum obstruction to the view of the production process, and enable essential work to be carried out on the installation and/or replacement of tools and for maintenance purposes by restricting access exclusively to the area where the work has to be done, if possible without the guard having to be removed or the protective device having to be disabled.

In addition, guards must, where possible, protect against the ejection or falling of materials or objects and against emissions generated by the machinery.”

And at 1.4.2 in relation to fixed guards that:

- “Fixed guards must be fixed by systems that can be opened or removed only with tools.

- Their fixing systems must remain attached to the guards or to the machinery when the guards are removed.

- Where possible, guards must be incapable of remaining in place without their fixings.”

BS EN ISO 14120:2015 provides additional guidance in the form of general requirements for the design, construction and selection of guards provided to protect persons from mechanical hazards.

For specifics relating to lifts, we refer to clause 5.5.7.2 of BS EN81-20:2014, which requires, in addition to the provisions of the Machinery Regulations, that, “The devices used shall be constructed so that the rotating parts are visible, and do not hinder examination and maintenance operation. If they are perforated, the gaps shall comply with EN ISO 13857:2008, Table 4.

The dismantling shall be necessary only in the following cases:

- replacement of a rope/chain;

- replacement of a pulley/sprocket;

- recutting of the grooves.”

Having considered the prescriptive provisions, it is interesting to look at some case law.

For a number of years, the approach in the lift industry was not to guard sheaves. The basis of this was of restricted access to machine rooms, with a warning sign on machine room doors and with access restricted to trained personnel. This approach was tested in the 1978 case of British Airways (BA) v. Henderson, in which Mr. Henderson, an environmental health officer (EHO), served an Improvement Notice under s.2.(2)(a) of the HSWA (failing to ensure the safety of persons in their employment) on BA in relation to unguarded lift machine room equipment. Whilst BA accepted that it had a duty to guard an overspeed governor (this being located on the floor and presenting a greater hazard), it appealed the Notice in relation to guarding of the machine sheave. The basis of the appeal was that of necessity for access to the sheave and ropes for inspection, a lack of which might create a greater risk, and with entrapment risks being mitigated in the restriction of access to trained personnel. Following a failed application by the EHO to amend the Notice to include an allegation of breach of s.3 HSWA (failing to ensure the safety of persons not in their employment, which would have weakened the appellant’s arguments) the appeal succeeded. In my mind, the decision was a somewhat tenuous application of the regulation, albeit that the appeal succeeded.

Whilst the EHO relied upon s.17(1) of the Shops, Offices & Railway Premises 1963 (which required the guarding of dangerous parts of machinery), BA cited s.17(3) (which provided for examination of a dangerous part whilst in motion if this could only be carried out whilst in motion) and upon provisions of BS2655 Part 10 and the fact that whilst pulleys required guards, sheaves were not specifically mentioned (albeit that this was superseded by BS5655-1 1979 within six months of the decision).

This situation prevailed for a number of years until the early 1990s when the introduction of The Provision and Use of Work Equipment Regulations (PUWER) 1992 resurrected questions relating to unguarded machine sheaves. Whilst some debate arose, a review of BS5655-1 1979, which provided an exception for “traction sheaves, hand-winding wheels, brake drums and any similar smooth, round parts” proved conclusive in that most sheaves of that time could not be considered “smooth, round parts.” And, who as a client or contractor would risk debating the difference in Court? Whilst the BS5655 provisions applied to new lifts, the limitation inherent in the “smooth and round” provision clearly undermined the decision in BA v. Henderson and, with the introduction of PUWER, changed the state of the art.

SAFed’s guidance on lift machine room guarding advocates an approach based upon risk assessment, which should consider the types of people entering the room and their particular competence and expertise, together with a holistic assessment of the overall risk. This approach reflects that taken in BA v. Henderson, although it must be recognised that the duty under Regulation 11 of PUWER is absolute and any associated risk assessment must, therefore, be suitable and sufficient, which, in practical terms, means the prevention of contact of a part of the body or clothing with any dangerous part of the machine.

In the case of an accident arising due to a deliberate removal of a guard by an employee or authorised person, any civil claim will be considered by way of an attribution of fault/causation and assessed on a contributory negligence basis. A Court of Appeal decision in Jayes v. IMI (Kynoch) Ltd. [1985] ICR 155 (CA), which involved injury due to a deliberate removal of a guard by an experienced manager, found 100% contributory negligence on the part of the injured manager. This is now considered unsound in that a finding of 100% contributory negligence is considered irrational. As such, a duty-holder invariably incurs a duty in relation to the management of machinery guarding and its removal.

Under EN 81-1, guarding of the pit tension pulley was limited to that necessary to mitigate the risk of the entry of falling objects/debris — in effect, a top cover. As a consequence of the introduction of EN 81-20 pit inspection controls, more extensive guarding is now required. So, guarding requirements may be considered to evolve in response to technological change.

The use of quick release fixings on guards has been prohibited for many years now and, realistically, has never formed part of an acceptable design approach to safety guarding. Perhaps the most longstanding and prolific quick release fixing is the wingnut which, despite its widespread use, is not an acceptable solution.

The widespread, and non-compliant, application of imperforate sheet metal panels in the fabrication and construction of lift guarding (simply because it’s cheap) has been a retrograde step in terms of safety and inspection. An example is shown in Image 1, with another example that clearly impedes inspection and maintenance in Image 2.

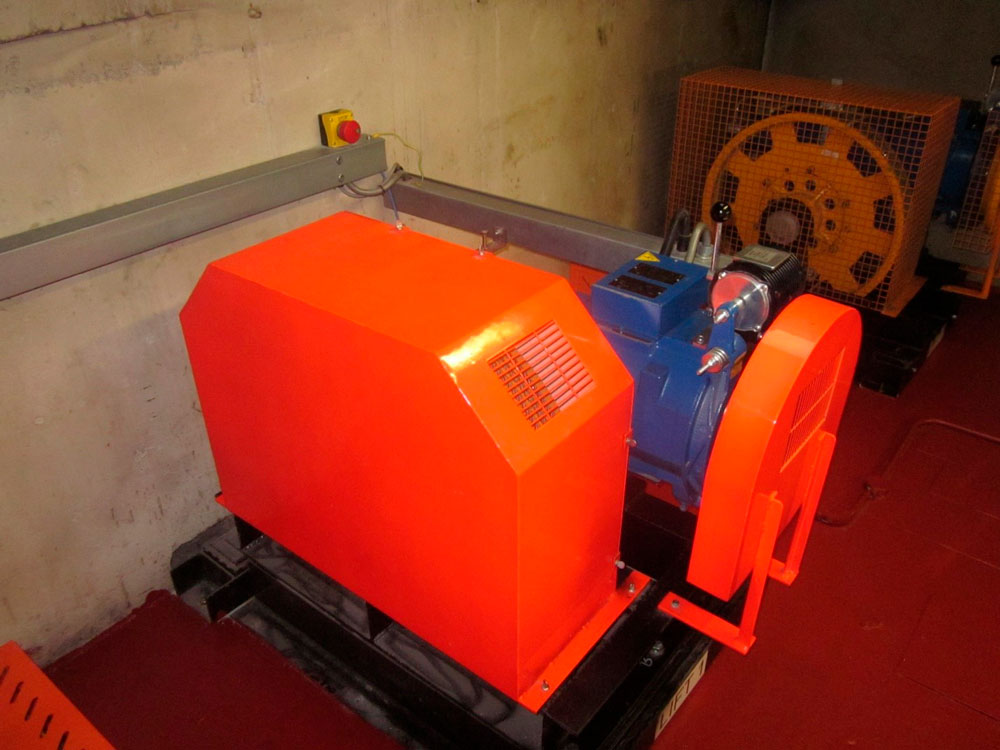

The traditional counterweight guards I recall from my Otis days provide a good example of quality guarding, which is well suited to its purpose, an example of which is shown in Image 3. The counterweight, and most importantly, the clearance between it and its buffer, are clearly visible from the landing without necessity to enter the pit. Traditionally, lift machine guards were well designed and constructed with an application installed to a complex machine shown in Image 4 and a more traditional arrangement in Image 5. These guards are more costly to produce than the imperforate sheet metal examples but are compliant and are, in fact, economic and effective when considered in terms of enhanced inspection and maintenance over the life of the installation.

Given the prescriptive detail of the regulation and guidance, and in light of the case law, I am amazed that we so rarely get it right and by the amount of poorly designed (and non-compliant) guarding that I encounter almost on a daily basis.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.