Safety Appliances for Lifts: 1895 (Part 1)

Aug 22, 2023

A look at the critical background and context of Umney’s paper

On 10 June 1895, Herbert W. Umney (1870-1958) presented an illustrated paper on lift safeties to the Society of Engineers. While presentations on lifts to learned societies were not uncommon — although they were far fewer in number than presentations on other engineering topics — an event that preceded Umney’s presentation meant that his paper attracted a higher level of interest than normal.

In the 19th century, such presentations typically included three parts: the presentation of the paper, commentary by members of the audience and a response by the author to the audience’s comments. Papers of high quality and which attracted particular attention by the membership were often published in a society’s proceedings with the publication including all three components: the paper, the recorded commentary and the author’s response. Umney’s paper, commentary and his response were published in the Society of Engineers Transactions for the Year 1895. The thoroughness with which Umney presented and illustrated his topic, coupled with the makeup of his audience — which included several of the founders of the British lift industry — offered unique insights into lift safety practices at the end of the 19th century. However, before delving into the paper, its historical context and author must be examined.

The significant event that preceded Umney’s presentation was the tragic death of Thomas C. Read (1854-1895), a popular member of Britain’s engineering community. On 25 February 1895, Read was killed in a lift accident that occurred in the Lloyd’s Register Building (located at No. 2 White Lion Court, Cornhill). The lift, manufactured and installed in 1891 by Clark, Bennett, and Co. of London, was a direct plunger machine equipped with a “balancing cylinder.” This type of hydraulic lift was developed in the late 1870s, and its basic operation was described in Waygood & Co.’s 1888 catalog:

“In raising the car, the ram is thrust out of a hydraulic cylinder of equal strength, by the admission of water into the cylinder, through the valve — the ‘working valve’ as it is called — which is controlled by the hand rope passing through the car, from top to bottom of the shaft in which the lift ascends and descends … In the case of a lift of any considerable size, it is necessary to economize the amount of water used, by balancing the dead weight of the moving parts … In which the water admitted to the lift cylinder is taken from a companion cylinder loaded with weights.”[1]

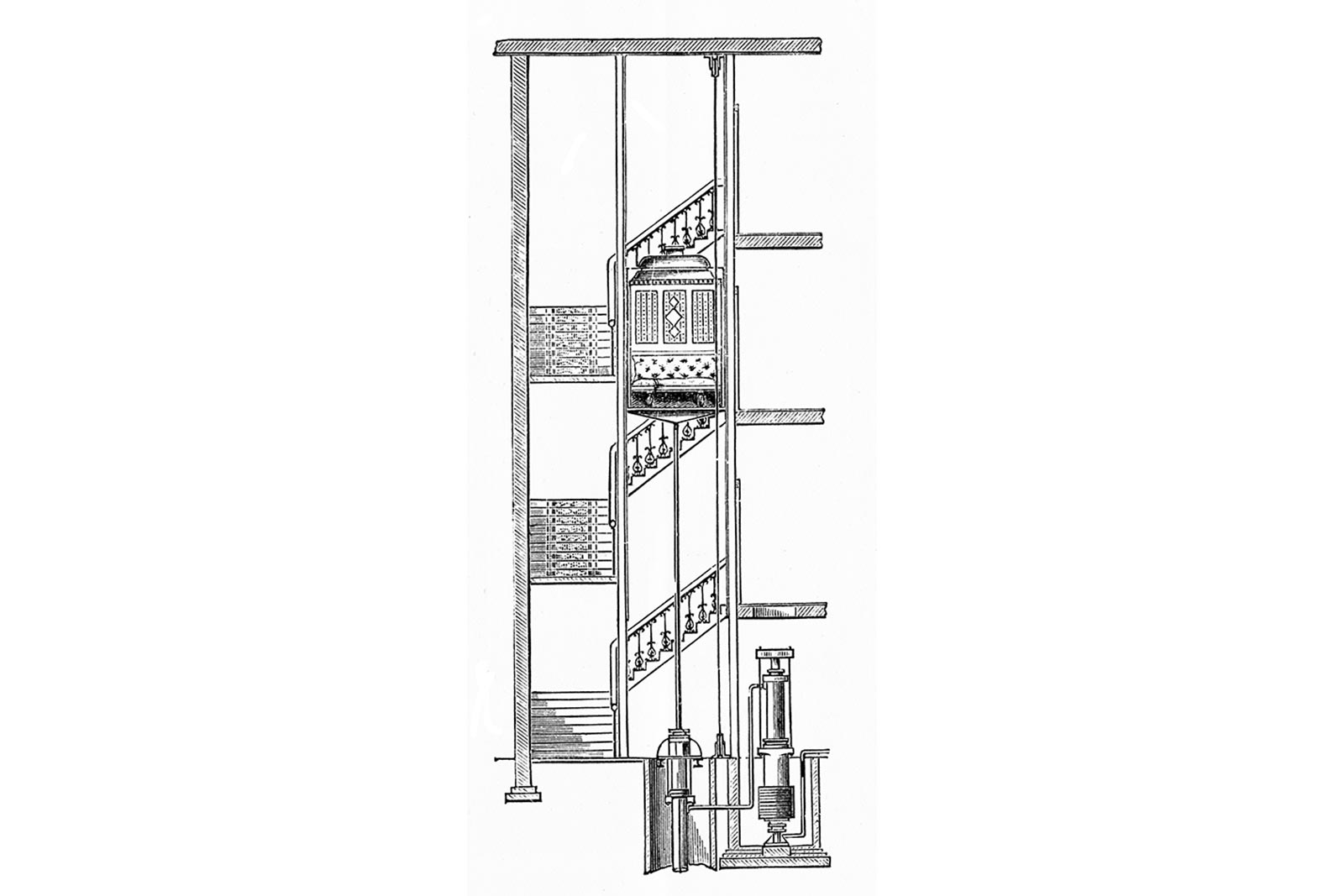

Although no drawings of the Lloyd’s lift have survived, it may be reasonable to assume it resembled Waygood’s design (Figure 1).

Read had entered the lift on the ground floor and rode up to the first floor, accompanied by J. F. Hill (a clerk) and Herbert G. Cartwright (the lift operator). When the lift reached the first floor, Cartwright opened the door and stepped out of the lift, followed by Hill. Just as Read placed one foot on the landing, the car suddenly dropped down the shaft, and Read fell down and forward, striking his head on the edge of the landing, after which he fell down the shaft (a distance of about 25 ft). Although he suffered significant injuries as a result of the fall down the shaft, the coroner determined that the initial blow to his head was the likely cause of death.

The London Evening Standard published a detailed account of the official inquiry into the accident. The primary cause of the accident was identified as the “fracturing” of two pipes due to the “crystallization” of their metal, which resulted in a sudden loss of water pressure.[2] The inquiry also revealed that the lift was undergoing repair while it remained in operation. James T. Milton (1850-1933), the chief engineer surveyor at Lloyd’s, represented the company at the inquiry. The coroner asked Milton: “We have been told that the lift was out of order, but was still continued to be used. Can you explain why that was?”[2] His response was:

“The balance arrangement had been out of order for more than six days before the accident, and it had been removed at my suggestion for repair, the difficulty in regard to it being a leakage, causing waste of water, but there was nothing structurally wrong. Since it has been in use for the last three years and a half the lift proper has never given a moment’s trouble until this accident. The lift was worked by two systems, the object of the second system being solely economy in the consumption of water. It was nearly always used by the balance system, that being the economical method. If that was out of order it was shut off and the lift was worked direct from the hydraulic main.”[2]

Papers of high quality and which attracted particular attention by the membership were often published in a society’s proceedings with the publication including all three components: the paper, the recorded commentary and the author’s response.

Milton also noted that, after the lift had been installed, it had passed a pressure test of 2500 psi and that its normal operating pressure was 750 psi. When the accident occurred, four workmen from the Glengall Ironworks Company were disassembling the hydraulic balance.

It is of interest to note that neither the coroner nor the jury asked for a detailed explanation of the lift’s operation to confirm that it could be safely operated without the balance. While the jury took only a few minutes to reach a verdict of “accidental death,” they did append a rider to their decision: “We are of the opinion that all lifts used for passengers should have some automatic arrangement by which similar accidents to the present unfortunate one may be prevented in the future.”[2] While this was, perhaps, a reasonable statement, a better question might have been: Given the widespread use of lift safety devices, why wasn’t one installed on the Lloyd’s lift? Lastly, Milton’s silence on this matter is also intriguing.

In the introduction to his paper, Umney noted the general absence of discussions on lift safeties, and he alluded to Read’s “accidental” death:

“Although numerous papers on lifts have been read and discussed at meetings of the different learned societies and institutions, the accessories have never received other than the merest comment. The author has therefore selected the details of safety appliances as the subject of the present paper, as he considers it of the utmost importance. With the memory of the sad death by a lift accident of a member of the profession fresh in his mind, the author offers no apology for the subject of the paper; but the contents are another matter, and on this score he would crave the indulgence of the meeting.”[3]

His request for indulgence on the part of his audience may have reflected the fact that, at age 25, he was the youngest person present. Of course, youth does not always equate to inexperience.

Umney was born in Surrey in 1870. His education began at the Stafford House School (Surrey) and, in 1881, at age 10, he was enrolled in Dulwich College (a well-known boarding school). He left Dulwich in 1887 and entered into a three-year “pupilage” or apprenticeship with R. Waygood & Co. in London. During this period, he also attended classes at the City of London College, where he studied under Prof. Henry Adams (1846-1935), and at Finsbury Technical College, where he studied under Prof. John Perry (1850-1920). Adams, the founder of the college’s engineering department, was a successful consulting civil and mechanical engineer with experience in designing hydraulic equipment, water systems and steel and concrete structures. Perry was a leader in the emerging field of electrical engineering. Following the conclusion of his apprenticeship with Waygood in early 1890, he remained with the company for an additional six months, working in their drawing office.

In late 1890, Umney left London and began pursuing course work at Yorkshire College, Leeds, where he studied under Prof. John Goodman (1862-1935), who was an expert in engineering mechanics. During breaks in his studies, he worked in the drawing office of Middleton & Co. (Southwark) and at the Broadway Testing Works (Westminster), where he worked under the direction of W. Harry Stanger (1847-1903). Stanger had founded the Testing Works in 1887 “for the mechanical and chemical testing of all structural materials in use by engineers.”[4] In mid-1893, Umney left the university to join Pickerings Ltd. (Stockton-on-Tees) as an assistant manager; a position he held until November 1894. In December, he joined Stothert & Pitt (Bath), a firm that specialized in the design and manufacture of cranes.

An indication of the impression Umney made on his professors and employers is found in the nomination form proposing his election to the Institute of Civil Engineers.[5] The form was submitted by Walter Pitt (1852-1921), chairman of Stothert and Pitt, and the “seconders” of his nomination included Percy K. Stothert (director), Henry Adams, John Goodman and W. Harry Strang.

The statement of qualifications, which outlined his education and employment history, noted that while a member of the Institute’s student section he had presented a paper titled the “Efficiency and Economy of Elevators.”[6] Unfortunately, a copy of the presentation has not survived. It is interesting to note the choice of a key term used in the paper’s title: elevators instead of lifts. His 1895 presentation included this same anomaly; the paper was titled “Safety Appliances for Elevators.” No explanation was offered for his preferred use of the American term over its British counterpart. Umney’s predilection for American terminology does not, however, diminish the fact that he brought to his topic approximately five years of experience in the lift industry, a broad range of educational experiences and, as will be seen, an avid interest in lift history. The latter was prominently featured in his paper and included one reference that requires an explanation.

Umney’s predilection for American terminology does not, however, diminish the fact that he brought to his topic approximately five years of experience in the lift industry, a broad range of educational experiences and, as will be seen, an avid interest in lift history.

In contemporary presentations on lift technology, it is not uncommon for speakers to refer to events about which they are confident their audience is sufficiently knowledgeable that no explanation is required. One such event, which Umney referenced in his paper, while not contemporaneous, clearly still resonated in the minds of audience members. He made a passing reference to “the well-known Paris accident,” which had “brought about the abolition of the practice of balancing the dead weight of the ram and cage in direct-acting lifts by overhead gear.”[3]

The “well-known Paris accident” had occurred in the Grand Hotel on 24 February 1878. A direct plunger lift, which employed two counterweights attached to the car, suffered a catastrophic failure that resulted in the deaths of three people. The system, designed by Léon Edoux (1827-1910), was assumed to be perfectly safe. On the day of the accident, the car ascended to the second floor to pick up two passengers who wished to travel to the first floor. When the lift operator began the descent, the connection between the bottom of the car and the top of the hydraulic ram failed, and the ram dropped down the shaft while the car, due to the action of the counterweights, was carried to the top of the shaft where it crashed into the overhead structure. The crash sheared the counterweight chains and the car and counterweights plummeted to the bottom of the shaft. As was noted in the inquiry, the lift was not equipped with any safety devices. The horrific nature of the accident, coupled with its occurrence in such a prominent building, resulted in it receiving international press coverage such that it was indelibly etched into the minds of British lift engineers and manufacturers.

Having explored the critical background and context of Umney’s paper, part two will examine the paper’s contents and its thorough discussion of British lift safeties.

References

[1] R. Waygood & Co., Hydraulic Passenger Lifts: A Guide to Intending Purchasers (1888).

[2] “The Fatal Lift Accident,” London Evening Standard (March 1, 1895).

[3] Herbert W. Umney, “Safety Appliances for Elevators,” Society of Engineers Transactions for the Year 1895 (1896).

[4] “Obituary: W. Harry Stanger,” The Journal of the Iron and Steel Institute (1903).

[5] Form A, For Election The Institute of Civil Engineers (28 September 1895).

[6] Hebert W. Umney, “Efficiency and Economy of Elevators,” read at a student’s meeting of the Institute of Civil Engineers (4 March 1894).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.