Solutions Needed to Ensure Children’s Safety

Mar 1, 2014

In this Readers Platform, authors James Filippone, P.E., and John Koshak, QEC, explore changes to the U.S. elevator code and common installations, which have combined to make private-residence elevators potentially hazardous for small children.

by James Filippone, P.E., and John Koshak, QEC

The possibility for children to become trapped in the space between elevator hoistway doors and elevator car doors/gates has been known for many years. Once they become trapped and the car moves, it can crush/asphyxiate them, resulting in serious injuries or fatalities. It is unacceptable that these injuries and fatalities to children still occur from well-known hazards.

The number of children seriously injured or killed will never be fully known, due to protective orders and destruction of documentation. However, one manufacturer reported there were 34 children injured or killed from 1983-1993 in New Jersey and southern New York State alone.[1] After the tragic fatality of an eight-year-old boy, one manufacturer chose to be part of the solution. It notified building owners of the hazard and offered free space guards.[2 & 3]

Inaction is not an option. We have to choose to be part of the problem or part of the solution.

This article will focus on the new issues, since the historical ones are likely well known in the industry. We will explain what the issues are for objective evaluation to prevent these tragic incidents in the future. Inaction is not an option. We have to choose to be part of the problem or part of the solution.

The Problem

Two physical elements allow child entrapment to occur: sill depth behind the closed swinging hoistway door, and door-to-door clearance between the closed swinging hoistway door and the closed car door or gate. Historically, the safety hazard has primarily been with swinging hoistway doors and car gates. More recently, the introduction of folding (accordion) car doors as a substitute for car gates created another safety hazard.

Children physically able to occupy the space behind the hoistway door are likely unaware of the hazard. It may be an easy rebuttal to claim parents have an obligation to watch their children at all times; however, this fallacy is not persuasive when the hazards are also not known by the general public. Furthermore, children sometimes leave their parents’ observation with a playful or independent intent. This is especially true in private residences.

Sill Depth

The 1921 American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) A17, Safety Code for Elevators (first edition) limited the landing sill depth to 4 in. for all types of hoistway doors on passenger elevators. The A17.1-1931 code (third edition) required a maximum 1-in. sill depth for swinging hoistway doors on new automatic passenger elevators, and immediate retroactive action was required to reduce sill depth to a maximum of 1.5 in. on existing elevators by filling in the space with a “suitable means” if necessary. The 1937 code (fourth edition) further decreased the sill depth to 0.5 in. for new elevators and continued the 1931 code’s retroactive requirements for existing elevators. The ASME A17.1.5-1953 Safety Code for Private Residence Elevators increased the sill depth to 2 in. The 1981 code allowed 3 in. maximum,[4] six times the maximum allowed in 1937. Your authors have not been able to find any documented reason/rationale for this increase.

Door-to-Door/Gate Clearance

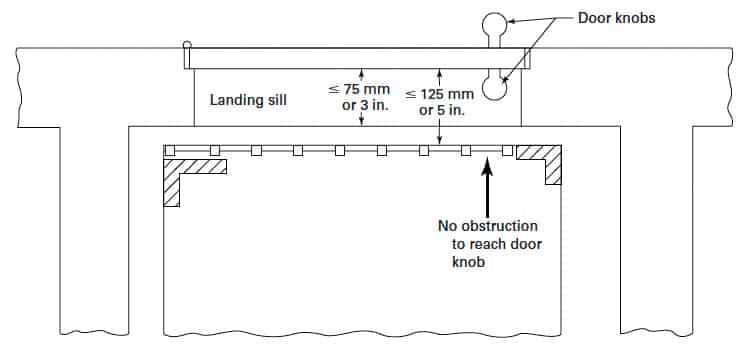

The second element, with even more safety significance than sill depth, is the door-to-door/gate clearance. Early code rules were based on a solid hoistway door and either a solid car door or a collapsible (scissor) car gate (Figure 1). These define two-dimensional planes for the purposes of measuring the clearances.

A17.1-1937 set a maximum of 4 in. between a swinging hoistway door and a car gate. This applied to all automatic passenger elevators. A17.1-1981 increased this critical dimension to 5 in. for private-residence elevators.[5] This extra 1 in. increased the hazard of entrapment in a critical way, yet is still permitted today. Anthropometric data for small children available since 1971 was apparently not taken into account when this change was made.

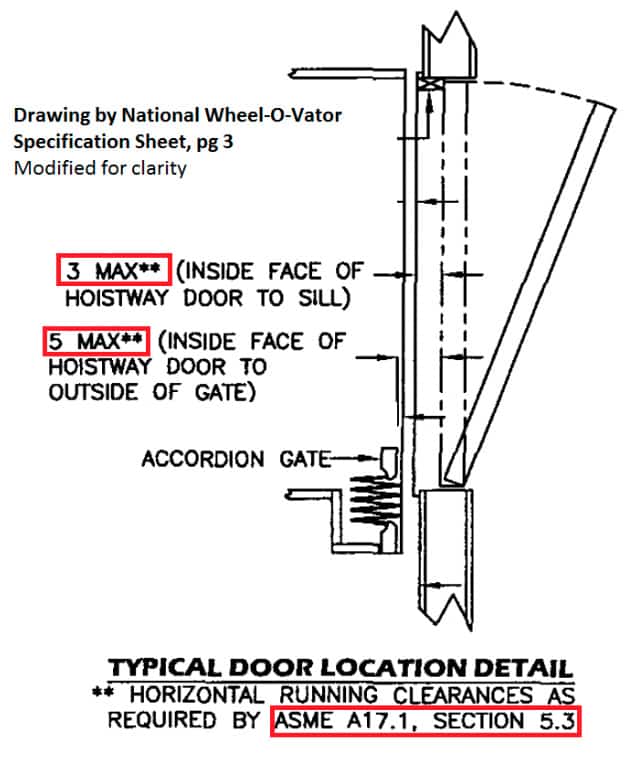

The final change in design that caused the most increase in hazard was the introduction of folding car doors into the marketplace. The folding door was apparently introduced to eliminate such hazards of collapsible gates as shear hazards arising from putting a hand through the gate openings while the car is moving. Introduced in the early 1990s, the folding car door increased the hazard of entrapment, because the door-to-door clearances were recommended to be measured to the peaks (not the valleys) of the folding doors by manufacturers/installers (Figure 3). The obvious valley formed by the folding door panels was ignored.

The A17.1 requirements are clear and unambiguous that the 3-in. sill depth and 5-in. door-to-door clearance are unconditional maximums. Inspectors often rely on the manufacturer’s incorrect clearance-measurement methodology.

When the maximum clearance measurements are taken to the peaks of the folding car door, the valleys create a space that enables children to stand between the folding car door and swinging hoistway door. Once the children are trapped, the car moves, resulting in serious crushing injuries or fatalities. This can be clearly seen in Figure 4 and in an associated video[6] made with an exemplar contemporary swinging hoistway-door entrance and folding car door. The video clearly shows children closing themselves in this dangerous space with ease.

Measuring the clearance between a swinging hoistway door and a folding car door must be to the farthest/deepest distance based on the clear and unambiguous code requirements. The consequences of measuring incorrectly can be tragic. In one case, where the clearance to the peaks of the folding door were less than 5 in. but the valley clearances exceeded 7 in., a three-year-old boy was severely injured and suffered permanent brain damage.

There is a need for the elevator industry to eliminate this safety hazard and protect children by revising the applicable code requirements.

Anthropometric Data

Proper code writing involves understanding hazards and ensuring mitigations are sufficient to eliminate or reduce the severity and/or frequency of hazards. This process is no different today than in 1921, except, as years go by, historical information adds to the hazard information used in determining which mitigations are necessary.

The standard for child clearances was set in the model building codes, when, in 1990, the Uniform Building Code limited baluster clearances to 4 in., and the National Building Code and Standard Building Code followed suit in 1997.[7]

In Building Standards Magazine, Elliott Stephenson, a structural and fire-protection engineer, championed a change from a 6-in. to a 4-in. clearance based on his research to reduce openings on guardrails used on balconies, landings and open stairways.[8] His data led to the following three points:

Almost no child one year of age or older can pass completely through a 4-in.-wide opening.

Approximately 50% of all children 13-18 months old can pass completely through a 5-in.-wide opening.

Virtually all children less than six years of age can pass completely through a 6-in.-wide opening.

This change to 4 in. in the building codes to eliminate hazards to children should have been the impetus to reduce the allowed door-to-door clearance in the elevator code and return the maximum clearance between the swinging hoistway door and car door/gate to the original 4 in. permitted when private-residence elevators were added to A17.1 in 1953. An examination of the anthropometric data for children illustrates that a child’s head and body fit into the space at current code dimensions. These dimensions must be reduced to eliminate this hazard.

Head Breadth

Detailed anthropometric data is available in several reports. One commonly used resource is the Snyder Report.[9] Table 1 contains excerpts of relevant data from this report. Considering the valley area of a folding door can be more than 17.8 cm (7 in.) deep, every child’s head (when turned sideways) in this chart will fit into the space. This is illustrated in Figure 4 and the associated video,[6] and it highlights the hazard of using folding doors and not considering the depth of the valleys.

Chest Depth

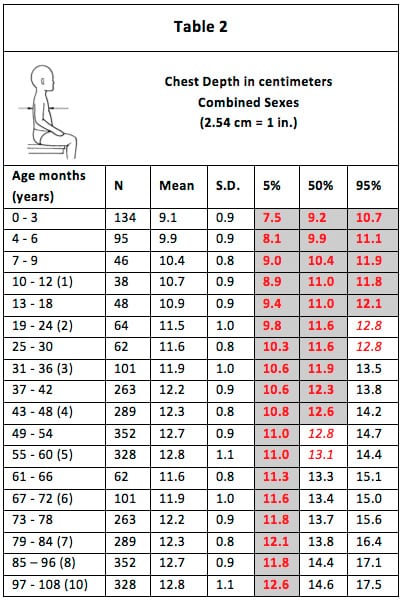

The second key dimension regarding child entrapment in the space is chest depth. Table 2 data is derived from the Snyder report.[9] Reducing the door-to-door clearance dimension to 7.6 cm (3 in.) would exclude 95% of all children age 0-3 months and older. A door-to-door clearance of 10.2 cm (4 in.) would exclude 95% of children 25 months old and older in the space.

Hazard Assessment

Code writing identifies hazards either by foreseeing a risk or by looking at actual risks. By now, the hazard is obvious. As discussed above, Figure 4 and the associated video[6] show an exemplar contemporary folding car and swinging hoistway door with a 12.7-cm (5-in.) door-to-door clearance measured from the peak of car door folds to a swinging hoistway door as instructed by manufacturers. It is clear children can fit into this space and can close the hoistway door at this distance.

Table 3 has the relevant data on the children in Figure 4. As can be gleaned from Table 4, these children were not very thin: all were closer to the mean than the extreme. The empirical data matches the anthropometric data, clearly illustrating that the hazard exists with the code requirements of today.

The Solution

“Safety codes and standards are intended to enhance public health and safety. Revisions result from committee consideration of factors such as technological advances, new data, and changing environmental and industry needs.” [11] New data in the form of serious injuries and fatalities must be considered a mandate for code writers to enact revisions to eliminate those hazards as a cardinal rule of elevator safety. These changes must consider the history, empirical testing evidence and child anthropometric data. The first step in all risk-reduction methodologies is to eliminate the risk.[10] There is no amount of warning that will mitigate this risk, and the solutions are easy to implement.

Manufacturers must redesign their elevators to eliminate these hazards, illustrated by the nature of these incidents. There are enough injuries and fatalities in number and severity that it is inexcusable to say it is too low a risk to require remedial measures. Manufacturers should lead the charge to make these changes as soon as possible. The next child should not fall victim to inaction.

It is clear children fit in this space and can close the hoistway door at this distance.

Anthropometric data for children must be used to ensure that the hazard is designed out of the industry’s products. Good and accepted engineering practices should be followed, and designs should exceed the code requirements. It is unacceptable to incorrectly instruct installers or AHJ personnel that the maximum clearance is between the swinging hoistway door and the peaks of folding car doors, despite clear and

It is clear children fit in this space and can close the hoistway door at this distance.

unambiguous code requirements to the contrary. Currently, there are designs in the elevator industry that significantly reduce the hazard and should be embraced (e.g., low-clearance hoistway doors and wraparound car doors), instead of folding doors. Manufacturers should not delegate the design of car doors to others. Installing companies must train their workers how to meet the proper code requirements and explain to them why this is so important. Code writers must thoroughly review all the applicable code requirements and use hazard assessment and anthropometric data for children to codify requirements that eliminate this hazard.

AHJs must be more vigilant in identifying where the hazards exist and emphasize the hazards when training their inspectors. In addition, they should provide guidance to owners in the form of regulation (or, at least, warn) owners/managers through all communication means available. Where retroactive requirements to reduce the clearances do not exist, regulations/laws must be enacted to eliminate this serious hazard.

Massachusetts has limited the sill clearance to 19 mm (0.75 in) and the door-to-door clearance to 75 mm (3 in.) since 1955. There are hoistway doors readily available for elevator applications that will meet a 1-in. clearance. AHJs should consider adopting these requirements, to which manufacturers currently design and install in Massachusetts.

Although mentioned last, maintainers have the highest responsibility. They are in frequent contact with the installed equipment and have the technical knowledge required to recognize the hazard. They must identify any hazards that exist, and promptly notify the owner of the hazard and offer space guards or new doors that eliminate the hazard.

Conclusion

There is a hazard that exists where children are seriously injured or killed by excessive clearances between swinging hoistway doors and car doors/gates in private-residence elevators. The clearance hazard has been known since at least 1931, yet the distance increased through the years and the introduction of the folding car door has created a new hazard. It is unacceptable that these injuries and fatalities to children still occur from well-known hazards. If the elevator industry fails to take the necessary actions, others (e.g., the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission) may make them for us.

It is noted that limited-use/limited-application elevators also specifically permit folding car doors. Also, “commercial” elevators (e.g., those conforming to parts 2 and 3) installed to A17.1-2007 arguably permitted folding doors, because they were listed in the definitions as a subset of horizontally sliding doors, but folding car doors were specifically prohibited for these elevators in A17.1-2010.

Figure 1: Typical relationship considered by the ASME A17.1.5-1953 Safety Code for Private Residence Elevators

Figure 3: Manufacturer’s detail of a typical door

Figure 4: (l-r) A four-, five- and seven-year-old child in a space that is currently code compliant

Table 1: Head breadths that fit into a 12.7-cm (5-in.) space between doors, the current maximum code-allowed clearance, are noted in bold red. Allowing for a construction tolerance of an additional 4 mm clearance is foreseeable (13.1 cm total). Head breadths that fit into this clearance are noted in italic red, increasing the hazard to include a larger population of children. Given the lack of stiffness of the folding door, if the car door has only 6 mm (1/4 in.) of deflection with a minimal force, the 12.7-cm (5-in.) dimension increases to 13.3 cm, increasing the hazard to include even more children.

Table 2: The ages of children whose chest depth would fit in a 12.7-cm (5-in.) space between doors, the current maximum code allowed clearance, appear in bold red. Allowing for construction tolerances, an additional 4-mm door-to-door clearance is foreseeable (13.1 cm), denoted in italic red. This increases the hazard to include even more children.

Table 3: Relevant data on the children who appear in Figure 4

Table 4: How the weights of the children who appear in Figure 4 (in bold red) compare to the anthropometric data for children

References

[1] Brinkman, Dennis, “Residential Elevator Child Entrapment Accident Reconstruction,” presented at “The XXV Annual Occupational Ergonomics and Safety Conference,” Atlanta, Georgia, June 6-7, 2013, Engineering Systems Inc.

[2] Bialy, Lou, “Space Between Swing Doors and Collapsible Gates Still a Hazard,” ELEVATOR WORLD, May 2003, p. 145-146.

[3] Bialy, Lou, “Space Between Swing Doors and Accordion Gates Still a Hazard on Private Residence Elevators,” ELEVATOR WORLD, November 2006, p. 48-49.

[4] American Society of Mechanical Engineers A17.1 Handbook 1981, New York, New York, 1981, p. xviii.

[5] American National Standards Institute/ASME A17.1-1981, New York, New York, 1981, p. 92.

[6] Cash, Krugler & Fredericks, LLC, “Jacob Helvey Elevator Injury Explained [sic],” (www.ckandf.com/articles/jacob-helvey-elevator-injury), accessed January 14, 2014.

[7] Stephenson, Elliott O., “Doesn’t It Count?” ESE Products Corp., Sun West City, Arizona, 2001.

[8] Stephenson, Elliott O., “Update on the Silent and Inviting Trap”, Building Standards Magazine, Jan-Feb 1991, p. 4-5.

[9] Snyder, Richard, et. al., “Physical Characteristics of Children,” Highway Safety Research Institute, University of Michigan, UM-HSRI-B1-75-5, May 1975.

[10] CAN/CSA-ISO 14798:12, Lifts (Elevators), Escalators and Moving Walks — Risk Assessment and Reduction Methodology, Canadian Standards Association, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada, January 2012, Clause 7.1 a), p. 16.

[11] ASME A17.1-2010/B44-10, New York, New York, 2010, Preface, p. xix.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.