VT growth made possible by a set of economic sectors remaining on a growth trajectory.

A trend where old buildings in South Africa’s major cities are getting renovated and upgraded is turning out to be a lead driver in the growth of the country’s vertical-transportation (VT) market. Government and private property developers are focused more on upgrading and replacing the existing VT equipment, with experts estimating the current share of the South African lifts maintenance segment is 65% of the total market share, while the rest is taken up by new installations, especially in greenfield buildings. “There are a lot of buildings in CBDs being revamped now, which is really an opportunity in the (lifts) industry,” said Hennie Hudson, a certified lifts inspector and manager at engineering consulting firm Projitech Consultants. Across South Africa, a set of economic sectors has remained on a growth trajectory, despite the country’s constrained growth. This has been supporting investments that have a direct bearing on the performance of the elevator and escalator market.

The economy shrunk by an estimated 0.7% in 2019 from 0.4% in 2018, reflecting in the sluggish performance of sectors such as real estate, even as the government promises additional commitment to heavy public spending on infrastructure development, despite delays in implementation of some approved projects. Focus on upgrading old buildings has been concentrated in the major cities of Johannesburg, Durban and Cape Town, with public spending on land and existing buildings for 2018 going up 16%, despite the overall growth of the construction industry having been in the doldrums since 2017.

“Spending on new construction works fell by 11.3%, from ZAR182 billion (US$9.8 billion) in 2017 to ZAR161 billion (US$8.7 billion) in 2018,” according to Statistics South Africa. According to the African Development Bank, the construction situation may change if South Africa’s economy grows by 1.1% in 2020 and 1.8% in 2021, despite “domestic and global downside risks.”

Demand for residential, retail and commercial space, a key driver in the performance of the elevator and escalator market, has recorded mixed growth in South Africa since 2014 with growing urbanization, which stands at about 66%, expected to exacerbate the surge in residential housing to an estimated 178,000 units annually. There is demand for retail space on the back of an expanding middle class that is driving demand for consumer goods supplied by the sector. The trend for commercial buildings has been an increase in vacancy rates, especially in Johannesburg, Durban and Cape Town, with market analyst Research and Markets saying although “property development is now showing signs of slowing down, developers are struggling to increase occupancy rates due to oversupply.”

Elsewhere, South Africa’s hotel industry is expected to record growth in investments. American commercial real estate services firm Jones Lang LaSalle Inc. (JLL) says the growth, especially in new hotels, is likely to be ZAR1.9 billion (US$102 million) in 2019. It adds that this will be invested into new hotels — around ZAR6.9 billion (US$372 million) in total over the next three years. “This translates into 3,900 new rooms across South Africa,” says JLL.

Moreover, development of tall buildings in South Africa remains another VT driver. With it, there is growth in the deployment of intelligent lifts. Africa’s new tallest, at 234 m, is now in Sandton, South Africa. At ZAR3 billion (US$162 million), The Leonardo is a 55-floor glass-and-concrete development. The mixed-use building, with both residential and commercial space, opened on March 3 with 230 apartments, 15,000 m² of office space, a hotel, a small retail section and penthouse floors. It replaces the Carlton Centre in Johannesburg as South Africa’s tallest building. Other previous holders of the top position in the country include Marble Towers and KwaDukuza eGoli Hotel Tower. Most of the previous tall buildings in South Africa were built in the 1970s and have become the latest segment in the country’s VT maintenance market. There is impetus to upgrade them to accommodate the increasing demand for housing infrastructure for both residential and commercial needs.

“A large share of CBD buildings are being converted from mere commercial buildings into residential apartments,” explained Hudson. “Although there is an elevator/escalator market in these old buildings, the lack of skills is a major issue in the industry.” For old buildings that require replacement of VT equipment, “The mixing of the old and new elevator or escalator units can be a challenge,” he said, “because much of the upgrading equipment is from Europe, while that for replacements come from China.” In other instances, he said elevator companies with production lines in South Africa are asking new housing property developers to:

“. . .build shafts according to their standard production’s product. Although these elevator companies have flexible products, this comes at an extra cost. In the South Africa full replacement market, what has become an issue is when it comes to installing a new elevator in an old building.”

The South Africa lifts industry is also expected to benefit from the maintenance and modernization of elevators and escalators, either in old public infrastructure facilities or those to be developed under the country’s National Development Plan, including schools, hospitals, public offices and state-developed commercial spaces.

Despite the positive outlook of South Africa’s economy and likely benefits to economic sectors such as the lifts industry, the country is struggling with an electricity supply crisis impacting the growth of the VT market. “Unreliable electricity supply has exacerbated the growth constraints, [and] small and medium-sized enterprises are especially disadvantaged in this environment,” said the International Monetary Fund in October 2019. According to Hudson, the electricity issues with South Africa’s power monopoly Eskom is a major consideration for property developers, as the unreliable supply impacts variable-voltage, variable-frequency drives. “The power supply issue is a factor to be taken into consideration in South Africa, because [these] drives are very sensitive to such situations,” he said.

Instability in electricity supply is not the only major challenge to South Africa’s VT industry. There is also a question of what to do with the dysfunctional elevators in buildings the government refers to as “hijacked.” “The dysfunctional lifts [in] hijacked buildings, especially in Kwazulu Natal and Gauteng, is a major challenge facing the lifts industry,” says Jacob Maletse, director, Department of Employment and Labour (DEL). “Hijacked” buildings are those that were abandoned during the post-Apartheid era by mainly white landlords but occupied by poor, mainly black, South Africans. The government says the buildings have since been taken over by criminal gangs and slumlords who charge exorbitant rent with little attention to safety and basic services.

In Johannesburg’s inner city, there are more than 500 derelict buildings, many with dysfunctional lifts. The local municipality has been trying, unsuccessfully, to evict illegal occupiers for rehabilitation and modernization. Furthermore, Maletse says South Africa is grappling with the issue of incomplete records on deregistration of lifts no longer in use and the slow pace of this process. However, in the long term, the South Africa lifts industry is hoping the government fast-tracks the development and implementation of the code of practice for inspection and testing for VT equipment. Additionally, South Africa is still exploring options to address the challenge of “lack of national or international standards for lifts inside wind turbines,” according to Maletse.

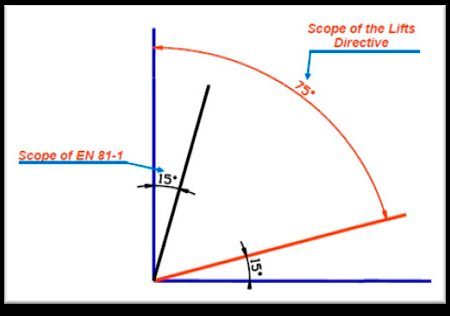

However, the November 2019 adoption of the SANS 50081-20 and -50 regulations, which are the local equivalents of the European Norms (EN) that focus on safety rules for the construction and installation of lifts, was a major step toward bringing clarity to South Africa’s VT industry, especially with the increasing Chinese influence in the production and supply of equipment. “We have had a couple of issues with equipment coming from China: although they say they comply with EN standards, when it comes to South Africa, we have to assist both the smaller companies and even multinationals in the country to make sure they comply with EN standards,” adds Hudson.

South Africa has an estimated 45,000 lifts, although no precise figures have been provided because of delays in the DEL to update records on deregistered elevators and escalators. “At this stage, it is unclear how many unregistered goods access lifts there are [in South Africa],” said Maletse.

With an annual 1,500 new lifts added to the market either as newly installed or replacement units, China continues to dominate the South African elevator and escalator market with an estimated 90% share of all imports. Hudson explained:

“There are about four multinational lift companies in South Africa, but even they import their equipment from China. [South Africa’s few local independent manufacturers] control a small margin of the industry, because they also rely on China for supply.”

South Africa could be going through a slow recovery from recession, but with the elaborate public expenditure anticipated under the National Development Plan and the increasing role the private sector is playing in real estate investments, the country’s elevator and escalator market has the potential to grow from its current levels in the medium and long terms.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.