Taking TODs to the Next Level

Jul 1, 2014

Integration of horizontal and vertical transportation will be needed in the clusters of density foreseen in U.S. urban centers.

Two-story buildings with elevators are not rare, but the need for vertical-transportation solutions really starts with the third floor. Buildings taller than four stories are where the market for elevators — design, installation, inspection, maintenance and emergency response — really gets interesting.

In the early 20th century, before mass ownership of cars, rail transit created dense central business districts in large cities in the U.S. and elsewhere. CBDs became clusters of skyscrapers called downtowns, where all the radial lines intersected. With wholesale adaption in the last century of automobiles as the primary means of getting around, downtown dominance declined in the post-World War II decades as stores and offices migrated to the suburbs. Once-vibrant, walkable neighborhoods declined, and most new construction evolved in the form of myriad subdivisions, big-box stores and malls. At highway intersections, parking-rich districts, mostly one-story sprawl with little need for elevators, emerged.

With wholesale adaption in the last century of automobiles as the primary means of getting around, downtown dominance declined in the post-World War II decades as stores and offices migrated to the suburbs.

Realty in the 21st Century

For realty developers, the 21st century is showing signs of change in demographics and lifestyle that point to movement away from addiction to cars. A 2010 Brookings Institute report found the most growth in the U.S. is occurring in large urban areas, which expanded 10.5% during the “tumultuous” decade of 2000-2010. That is almost double the rate of the country as a whole. We are an increasingly diverse, multicultural nation that is now one-third non-white. We face a surge in the number and vitality of senior citizens, as more than 100 million Baby Boomers move into retirement.

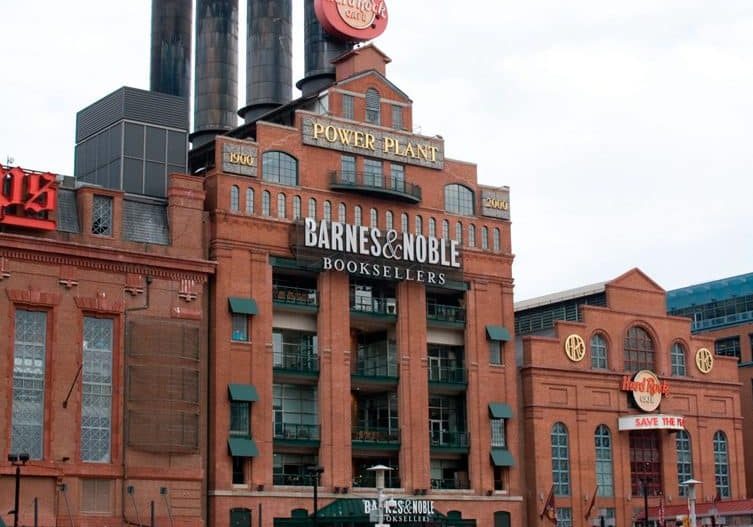

We have become a predominantly urban nation. In 1900, 45% of Americans lived in the 100 largest metro areas. In 1950, it was 56%, and in 2000, 65%. Today, New York City (NYC) is on a construction binge as it recovers from 2001 and 2009. Looking broadly across the U.S. demographic map, America is concentrating in large metro regions.

To reduce new traffic generation by this infill growth and the repurposing of old industrial and office buildings, urban planners and real estate investors often promote transit-oriented development (TOD). The idea is simple and hardly new: put tall buildings around transit stations. As TOD gains popularity, new markets for elevators, escalators and moving walks open up.

One way for TOD to gain traction is to incorporate modern, small-scale mini-transit systems known as Automated Transit Networks (ATN) to extend the reach of rail transit stations. ATNs can ramp up and down at steeper slopes than rail transit (10% versus 2%), so sections of guideway can be easily placed underground, near-grade or elevated — to the second- or third-floor levels, or even higher. Stations are of modest scale, and can be readily integrated into buildings’ lobbies.

In other words, vertical placement of modestly scaled ATN guideways and stations that deliver access to superior taxi-like services is flexible. This opens up exciting possibilities for district circulation that can and should be oriented to a transit station. For land-use planners, ATNs provide attractive ways to intercept street traffic in peripheral parking intercepts.

Station Elements and Needs

Rail stations create traffic and parking needs. Increased traffic and parking demand are two topics that get immediate attention in local politics. Stations attract people on foot, on bikes, in taxis and on buses, as well as in cars. If traffic and parking are not well planned and managed, conflicts quickly arise. Vying for space is further complicated by development pressures. Foot traffic makes a station site attractive for commerce.

The idea [of transit-oriented development] is simple and hardly new: put tall buildings around transit stations.

TOD adds density — “floor space” to planners; “square footage” to real estate professionals; or, in the plain language of common folk, tall buildings crowded together that need walkable, clean and safe streets. Whatever the term, for too many Americans the idea of urban density conjures up images of congestion and conflict.

Will TOD districts be good places to live? Will many Americans ditch single-family houses with lawns to live in apartments, condos and townhouses in clusters of density around rail stations? In the 20th century, the answer was — very few. Today, the answer to that same question is — a lot! With retiring Baby Boomers and people of all ages with diverse, multi-ethnic lifestyles, TOD prospects are rosy. We need ways to enhance and extend them.

TODs will be hubs of everyday commerce, programmed civic happenings and spontaneous interactions. They will also be multi-modal with bike-share stands, taxis, mini-rentals of cars and carts, and market-priced parking for those who do drive cars. Elevators, escalators and moving walks can find useful roles interconnecting it all and reducing traffic in the core around the station.

Looking broadly across the U.S. demographic map, America is concentrating in large metro regions.

In sum, these new urban districts will be mobility hotspots with density massed around them — possibly above and below the transit station itself, as well. As communities plan them, the need for integration of vertical and horizontal circulation will create planning scenarios that need the expertise of the vertical-transportation industry.

Extending Reach with Horizontal Elevators

With decades of experience at airports, hospitals, casinos and leisure districts, automated people movers (APMs) offer ways to extend the reach of a transit station to sites beyond the quarter-mile radius usually attributed to rail impacts by planners and real-estate agents. Almost 200 of them are in operation around the world.

For land-use planners, [automated transit networks] provide attractive ways to intercept street traffic in peripheral parking intercepts.

ATN is a more complicated and interesting form of APM. It can be designed as a dense mesh of modestly scaled guideways and stations that can be the mini spine of a whole district, making it easy to live without the burden of owning and paying for a car. ATN + TOD offer a way to satisfy mobility and connectivity needs in the transit-hungry, low-density neighborhoods of American cities. With ATN feeding metro stations, the whole city can be accessed within a five-minute walk.

Airport Districts and TODs

Airports and the business districts around them are prime candidates for the first ATN-served TODs. More and more trade is aviation-oriented, so these districts are growing with private investment. They need efficiency and easy access to the airport. In fact, many recent airport APM projects are landside — linking terminals to parking, car rentals and hotels. Airport officials are comfortable with APMs, which started seeing success in the 1970s.

San Jose, California, has looked at ATN for its airport connectivity, but so far has not committed to building one. Individuals and small groups have tried to advance such notions in Seattle; Baltimore; Bologna, Italy, and Helsinki. Urban ATN studies are underway north of Stockholm, Sweden, with Stockholm Arlanda Airport, two adjacent suburbs, landowners and international investors. Professor Shannon McDonald of Southern Illinois University has graduate students looking at design options.

These visions will be pushed forward at the 8th Podcar City conference, September 3-5, 2014, at Stockholm Arlanda Airport. Learn more at www.podcarcity.org.

ATN-enhanced TOD at airports and elsewhere needs to integrate vertical transportation. In the right political and professional contexts, they may live up to the visions contemplated by Elevator World, Inc. founder William C. Sturgeon back in the 1980s.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.