The 20 Tallest in 2020: Entering the Era of the Megatall

Mar 1, 2012

A study of the rising height of skyscrapers and the future of “megatall” buildings

by Nathaniel Hollister and Dr. Antony Wood

Within this decade, we will likely witness not only the world’s first 1-km-tall building, but also the completion of a significant number of buildings more than 600 m (around 2,000 ft.) – that’s twice the height of the Eiffel Tower. Two years ago, prior to the completion of the Burj Khalifa, this building type did not exist. And yet, by 2020, we can expect at least eight such buildings to exist internationally. The term “supertall” (which refers to a building over 300 m) is thus no longer adequate to describe these buildings; we are entering the era of the “megatall.” This term is now officially being used by the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH) to describe buildings more than 600 m in height, or double the height of a supertall (Figure 1).

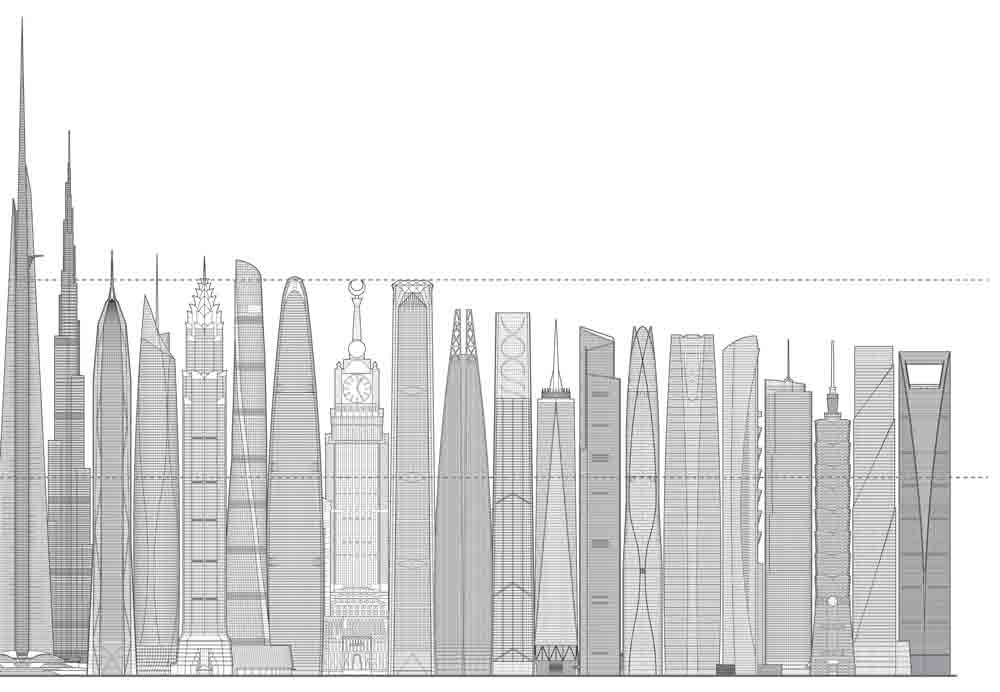

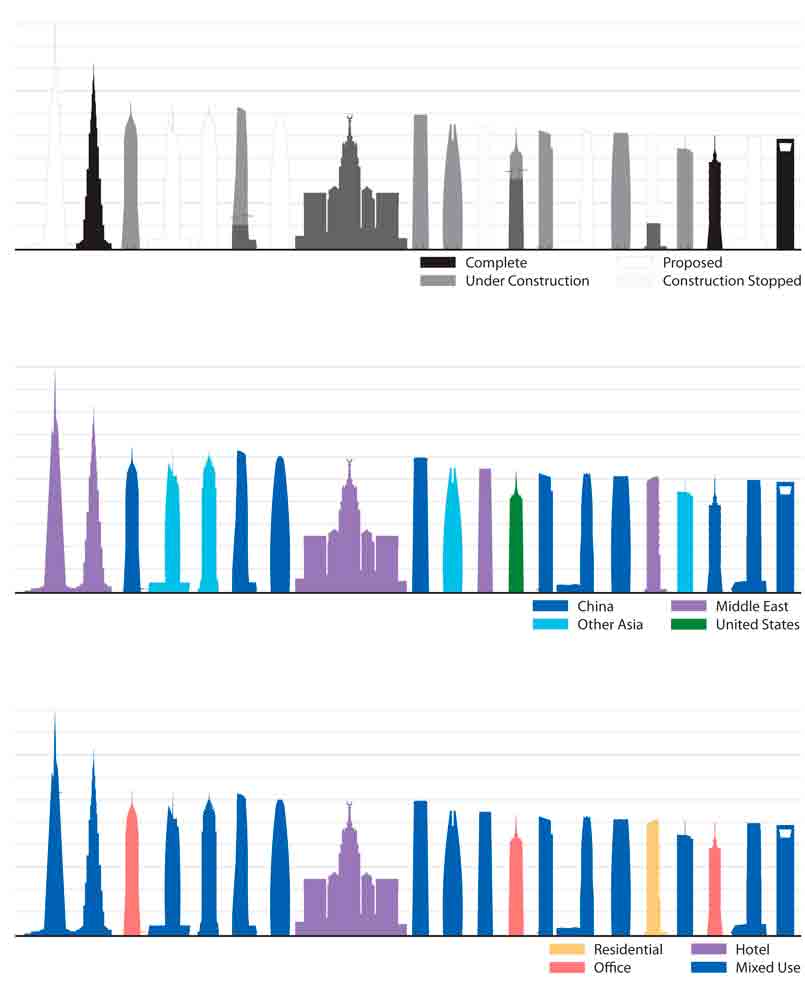

Buildings included in this study are either built, under construction or considered real proposals. Projects that have commenced construction, but with works currently halted, are also included if there is a strong possibility of the project progressing to final completion. A real proposal can be considered such if it has a specific site with ownership interests within the building development team, a full professional design team progressing the design beyond the conceptual stage, formal planning consent/legal permission for construction (or is in the process of obtaining such permission) and a full intention to progress the building to construction and completion. Furthermore, this research only considers projects within the public domain that have the consent for inclusion from the respective client/consultant teams. Because of this multifaceted inclusion criteria, a number of prominent projects were not included in the study, including: India Tower, Mumbai; Triple One and Hyundai Global Business Center, Seoul; and Zhongguo Zun, Beijing.

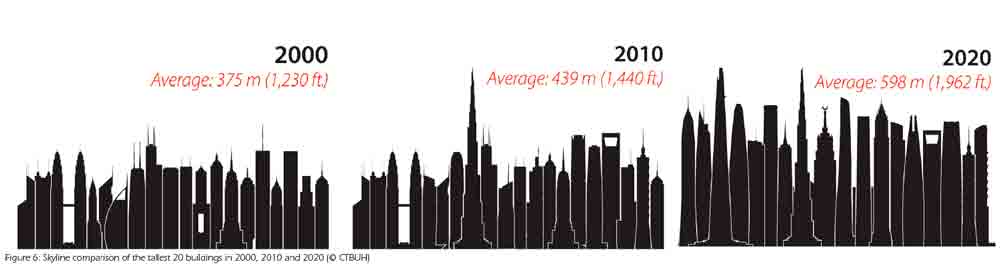

As we started the 21st century, just 11 years ago, the Petronas Towers held the title of “The World’s Tallest” at 452 m (1,483 ft.) in height. Taipei 101 took the title in 2004, at 508 m (1,667 ft.). Then, at the end of the decade, the Burj Khalifa set new standards at 828 m (2,717 ft.) – more than half a mile high. Now, with work set to start onsite in January 2012 for Jeddah’s 1,000-m-plus Kingdom Tower (Figure 2), we can expect that in a mere two decades (2000-2020), the height of the “World’s Tallest Building” will have more than doubled. What is perhaps the most interesting aspect of the study is that the previous world’s tallest mentioned above now barely make the list at all. In just two decades, Petronas will have gone from tallest to 27th-tallest in the world, and Taipei 101 just scrapes into the study at 18th place. When we take into account that new projects not included in this study will surely be announced and built throughout the next decade, one can predict that, with the exception of the Burj Khalifa and Mecca Royal Clock Tower, the tallest 20 buildings in 2020 are not yet built (though a number are already under construction [Figure 3]). The tremendous change the tall-building industry has seen in two decades is clearly shown by a juxtaposition of three skylines: the tallest 20 buildings in 2000, 2010 and 2020 (Figure 6).

It is also useful to understand the tallest 20 in 2020 in the context of global tall-building trends. Although the average height of these 20 buildings is predicted to be 598 m (1,962 ft.), at the end of 2011, there were still only 61 buildings currently over 300 m (the threshold for “supertall”) in existence. In fact, until recently, the completion of a supertall was a rather rare occurrence, with only 15 supertalls being completed in the 65 years between the world’s first such building (New York’s Chrysler Building, 1930) and 1995. It was only in the mid 1990s that it became common for more than one supertall to be added to the list annually, with 1995 being the last year when no supertalls were completed. Now, less than two decades later, the number of supertalls completed annually has entered double digits, and this figure is set to continually rise. Meanwhile, the number of megatalls set to be completed in the upcoming decade is similar to the number of supertalls completed in the 1990s (Figure 7). In terms of height, 600 m seems to be the new 300 m.

Not only increasing in height, the “Tallest 20 in 2020” also demonstrate a diversity in project location not previously seen in the world’s tallest 20. The projects are scattered across 15 cities in seven countries. China, with 10 of the 20 projects, clearly stands out as the country most rapidly pursuing the supertall design, followed by South Korea (3), Saudi Arabia (2), and the U.A.E. (2). If we analyze via a larger geographic region, however, the picture becomes even more pronounced. Asia (not including the Middle East) accounts for 70% of the buildings (14). The Middle East counts for 25% (5). The only other region represented in the study is North America, where New York’s One World Trade Center is the only tower in the western hemisphere to make the study. If we consider the Middle East as part of continental Asia, then Asia contains 19 of the 20 projects, certainly adding impetus to the upcoming CTBUH 9th World Congress, which will take place in Shanghai in September with the theme of “Asia Ascending: Age of the Sustainable Skyscraper City.”

With more than 1.3 billion citizens and a rapidly urbanizing population, China is perhaps the country with the most obvious reason for building tall. The 10 Chinese projects show great diversity in location, spread across seven cities: Shenzhen (2), Shanghai (2), Tianjin (2), Wuhan (1), Guangzhou (1), Dalian (1) and Taipei (1). The tallest of these, Shenzhen’s Ping An Finance Center (Figure 8), is now under construction and scheduled for completion in 2015. Once complete, the project will provide over 300,000 m2 of office space, and become the country’s tallest building and the world’s tallest office building. Also in China, the 632-m (2,073-ft.) mixed-use Shanghai Tower (Figure 9) will complete a supertall cluster in the city’s Pudong area, as it sits alongside the Shanghai World Financial Center and the Jin Mao Building. The Shanghai Tower’s dual-skin design provides atrium space containing “gardens in the sky” between skins every 12–15 stories. The project began construction in 2009 and is scheduled to be completed in 2014.

South Korea, a country with a population about 1/25th that of China but twice as dense by area, contains a somewhat surprising three of the 20 projects, two of which are located in Seoul. There are many reasons for this dramatic increase in supertall construction in South Korea, a country that has never had a single building within the world’s tallest 20 and is now on the verge of having several. Perhaps the foremost reason is a general feeling that South Korean cities lack the “iconic” or “landmark” buildings that many world-class cities contain. Seoul’s tallest planned building is the 640-m (2,101-ft.) Seoul Light DMC Tower (Figure 10), located at the western edge of the city overlooking the Han River. The tower will generate power to reduce its building’s energy usage by around 65%. Seoul is also home to the now-under-construction Lotte World Tower, a 555-m (1,819-ft.) supertall scheduled to complete in 2015. Besides these two significant buildings, the city has two additional projects in the works that have not yet received planning permission. Thus, they (the 620-m-tall Triple One and 540-m-tall Hyundai Global Business Center) are not included in the 2020 study. This means Seoul could potentially contain as many as four of the tallest 20 buildings in 2020.

Where can we expect the next nucleus of tall building construction globally? The Signature Tower (Figure 11) perhaps predicts the answer to this question. Indonesia’s current tallest building is Wisma 46, completed in 1996 at a height of 262 m – less than half the height of the proposed Signature Tower. In fact, much of South and Southeast Asia (including Indonesia, India and Vietnam) seem ready to become among the next centers of skyscraper construction. Together, the three mentioned countries represent nearly a quarter of the world’s population and yet contain no supertall buildings and a total of only four buildings more than 250 m tall. Signature Tower is therefore seen to herald the coming of the supertall to these countries. Excavation for the project is set to begin during the first quarter of 2012. Another significant project in this area, Mumbai’s planned 700-m India Tower, was not included in this study, as construction has stopped, and final completion is therefore not predictable. However, the presence of these two possible megatall projects point to the dramatic potential of this area.

Five of the Tallest 20 in 2020 projects are located in three countries in the Middle East: the U.A.E., Saudi Arabia and Qatar. These projects include the current world’s tallest (Burj Khalifa), the future world’s tallest (Kingdom Tower) and what is soon to become the world’s second tallest (Mecca Royal Clock Tower Hotel [Figure 12]). Quite obviously, a motivating factor in all of these projects has been to push the boundaries of technology and accomplish feats never before imagined. The Burj Khalifa exemplifies this fact. The next decade of supertall building construction will, in one sense, fill the gaps between the record-breaking Burj Khalifa and Taipei 101 (the world’s tallest building until January 4, 2010). Thus, 15 of the Tallest 20 in 2020 fit into this 320-m gap, with only Kingdom Tower exceeding the height of the Burj Khalifa.

Having discussed four regions/countries in the eastern hemisphere (where 19 of the projects are located), we turn to the opposite side of the world for the remaining project. One World Trade Center Tower (Figure 13), in New York City, is set to become the tallest building in the western hemisphere in 2013. In the 2020 study, the project comes in as the world’s 12th-tallest building. The building’s final height of 1,776 ft. (541 m) points to the U.S.’s Declaration of Independence and birth as a country. Located near the site of the old World Trade Center (WTC) buildings, the designers faced tremendous challenges in terms of space constraints, security apprehensions and millions of concerned citizens. In the case of One WTC, there were strong economic motivations to build tall to provide valued office space in one of the economic centers of the world, as well as strong emotional motivation to overcome the tragic events of 9/11.

The Tallest 20 in 2020 study ultimately underlines a now well-known fact: the skyscraper is here to stay. Shortly after 9/11, many predicted the death of the tall building, but as the study shows, skyscrapers are increasing in number, height and diversity. The ever-increasing and rapidly urbanizing global population will continue to drive cities higher.

Not long ago, building height was primarily restricted by structural limitations. In the late 1800s, Chicago’s Monadnock Building demonstrated the maximum height achievable with a masonry structure, while still providing economically feasible space efficiency. Over the 19th century, many advances in the fields of structure, construction and transportation (to name a few) allowed for a steady increase in building height. Now, the tremendous heights being achieved globally demonstrate that many of the physical constraints that once restricted height have been broken. The question for humanity is no longer “How high can we build?” but “How high should we build?”

With every increase in height, there are energy implications in the construction, maintenance and occupation of a building. Additionally, with added height comes less space efficiency, as structural members and service cores increase to service the increased height of the building. At what point are the significant benefits of increased density provided by building tall overtaken by the energy repercussions of height? This elusive figure is most certainly affected by the technologies of the day. Half a century ago, a megatall would have been considered possible only within a dream. It is now a reality. Is it not possible that we could soon see the emergence of a zero-energy megatall? Just as we pushed the structural boundaries of height, we must now continue to push the boundaries of environmental engineering in order to progress the tall typology. For, as skyscrapers continue to multiply, their effect on our cities – visually, urbanistically and environmentally –continues to increase exponentially.

Figure-1

Figure 2: The world’s tallest is set to change yet again in 2018 with the completion of Jeddah’s Kingdom Tower. (© Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture)

Figures-3-4-5

Figure-6

Figure 7: Supertall and megatall building completion, showing a significant projected increase (© CTBUH)

Figure 8: The Ping An Finance Center will become China’s tallest building. (© Kohn Pedersen Fox)

Figure-10

Figure-11

Figure-12

Figure-13

Figure-14

Figure-15

Figure-16

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.