The Bostwick Elevator Gate

Apr 1, 2018

The Unlikely Story of How a Patent Acquisition became Synonymous with sliding, collapsible metal elevator gates

One of the most iconic components of many late 19th- and early 20th-century elevators was the folding or collapsible metal gate. The visual characteristics of these gates, with their open network of crisscross steel or bronze bars, and the ratchet-like sound that accompanied their opening and closing, constituted defining aspects of the user’s experience. While these images and sounds are typically associated with American elevators — today primarily “experienced” in old, black-and-white movies — this gate type was equally popular in Europe. Although numerous variations were designed and manufactured, one of the first such gates, and the one that set the standard for this typology, was the Bostwick folding elevator gate.

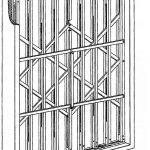

This story begins with James E.Q. Maddox of Cincinnati and his patent for a folding gate system: “Improvement in Gates,” U.S. Patent 191,984 (June 12, 1877). The gate employed a somewhat inelegant design that used iron “knuckle joints” to facilitate the folding action (Figure 1). Maddox stated his gate could be “expanded and contracted to a very great extent for the purpose of closing the space in the hallways of stores, on the line of the street and for other uses.” In 1878, Maddox partnered with George P. Humphries of Alexandria, Kentucky, to reengineer his design, and a second patent application was filed in mid 1878 and awarded in 1879: “Improvement in Gates,” U.S. Patent 213,119 (March 11, 1879). The pair expressed the essence of their design in terms of its contrast to the original:

“Our improvement. . . consists in so combining a series of cross and connecting braces or bars with the pickets, instead of employing knuckle joints, as to strengthen and support the gate, and adapt it to slide upon its support without changing the vertical position of the pickets, and at the same time preserving their parallelism when the gate is opening and closing.”

Although the patent drawing was a somewhat clumsy rendering, it expressed the visual and operational potential of the new system (Figure 2). Like the original patent, the gate’s imagined use was for “hallways and other places.” Regrettably, nothing is known about either inventor.

The reasons Maddox and Humphries assigned one-third of their rights to Walter W. Bostwick of Cincinnati are also unknown. Bostwick was the owner of W.W. Bostwick & Co., founded in the early 1870s. The company sold a wide range of products, including jelly and lard presses, and a unique lumber-cutting device marketed as the “Giant Riding Saw.” The impact of Bostwick’s partial ownership of the 1879 gate patent was immediately reflected in the company’s advertisements. The following year, it described itself as a manufacturer “of folding iron and steel gates and gratings.” In 1881, W.W. Bostwick & Co. was awarded a Silver Medal for “Folding Gates for Doors and Windows” at the Ninth Annual Cincinnati Industrial Exhibition. The gate system on display was doubtless predicated on Maddox and Humphries’ design. It is also possible that, by this date, it was referred to as “Bostwick’s Folding Gate,” and that Walter Bostwick had acquired full rights to the patent. These suppositions are supported by the fact that Bostwick embarked on an unusual marketing campaign the same year.

The August 13, 1881, issue of American Machinist announced the formation, in Chicago, of Bostwick Folding Iron Gate Co., which was established to pursue “the manufacture and sale of folding iron gates in the State of Illinois.” The October 28, 1881, issue of Nashville newspaper The Tennessean also announced the founding of Bostwick Folding Iron Gate. However, this company was in Nashville and presumably chartered to sell Bostwick gates in Tennessee. On December 12, The Tennessean ran an advertisement for the new company: “Architects, bankers and others will take notice that the Bostwick Folding Iron Gate Co. is ready to take orders for iron door gates and iron window protectors,” it read. “Until we shall have time to establish a manufactory here, this company proposes to take your orders and have them filled.” Clearly, the absence of a factory wasn’t going to stop the fledgling enterprise.

Walter Bostwick left Cincinnati in 1882 or 1883 and moved to Brooklyn, New York. His departure coincided with an announcement by L. Schreiber & Sons of Cincinnati, in which they declared that they were now the sole “manufacturers of Bostwick folding and extension iron gates and guards for Ohio.” This state-by-state business strategy continued throughout the 1880s. The Maryland Folding Iron Gate and Guard Co. of Baltimore was established in March 1884, followed by the creation of the Buffalo Folding Iron Gate and Guard Co. of Buffalo, New York, in September. The advertising copy published by the Buffalo company was the first to mention that the Bostwick gate was “especially adapted” for use with elevators.

Bostwick played varying roles in these companies, from investing directly in and serving on the board of directors, to apparently selling, in essence, a type of franchise. In addition to founding new companies, he also sold the rights to manufacture his gate to established companies that specialized in decorative metal work. These included the William R. Pitt Composite Iron Works in New York City (1883) and the Providence Architectural Iron and Metal Works in Providence, Rhode Island (1886). By 1886, both companies were also advertising the Bostwick gate as suitable for use with elevators. This unique marketing and business strategy also extended beyond the U.S. In February 1885, Bostwick, through an English intermediary, filed a patent application in the U.K. for “folding gates.” In 1887, Bostwick filed two additional English patent applications: one for “gates and window guards” and another for “folding shutters.” He filed these applications himself. In late 1886, he appears to have left the U.S. and by February 1887 was living in London.

These events coincided with the formation of yet another company intended to manufacture and market the Bostwick gate. The September 10, 1887, issue of the British magazine The Builder included a brief article titled “Folding Steel Gates and Shutters,” which discussed products “patented by the Bostwick Folding Steel Gate and Shutter Co.” However, the following year, a different British magazine, The Engineer, reported the registration of another new company, the Bostwick Gate and Shutter Co. (Ltd.), with Bostwick listed as a shareholder. This company was described as holding the “British, colonial, and foreign patent rights to Walter W. Bostwick, for folding and steel gates and shutters.” This second company, with its subtle name change from the first, became the official outlet for marketing and manufacturing Bostwick folding gates in the U.K. Press reports in English technical journals highlighted the usefulness of this “American invention,” and the November 16, 1888, issue of British Architect noted:

“The gates can be readily applied to almost any opening, and constitutes the simplest, most convenient and thoroughly effective form of protection for entrance doorways, windows, lift wells, etc. that we have yet seen. They have already been applied to a very large number of important buildings, and the demand for them, we understand, is constantly on the increase. We are not surprised.”

The reference to the gate’s suitability for use on “lift wells” follows the pattern that had emerged in the U.S. two years earlier. In addition to obtaining British patents, Bostwick Gate and Shutter also patented the design in Switzerland and marketed it throughout Europe.

In 1899, Colliery Engineer Co., publisher of the International Library of Technology (a series of correspondence-school textbooks), published Ornamental Ironwork, a booklet that included a detailed technical description of a Bostwick-style gate. The description was keyed to a series of three drawings that illustrated the gate’s key components (Figure 3):

“An elevation of the sliding or folding gate, protecting the entrance to the car, is shown in Fig. 3a, while Fig. 3b shows a large-scale detail of the bottom of the sliding post of the gate n and the guide o in which it slides. The vertical members of the gate are each composed of a pair of 1/2-in. channels as shown at a in Fig. 3c, which is an enlarged plan. Between these channels, the diagonal lattice bars b are secured as shown, with washers c between them to prevent their rubbing together as the gate is opened and shut. The rivets securing this latticework to the channels are not driven tight but are left sufficiently free to play up and down in the slotted openings shown in the elevation, Fig. 3a, at a. Thus, the gate, which effectively bars the 2-ft., 7-3/4-in. opening in the car, occupies, when open to its fullest extent, only the width of the seven vertical channels, or 3-1/2 in. On the exterior channel, a 1/2- X 1/4-in. guide is riveted, as shown at n in Fig. 3b, and on the underside of the Z-bar flange, a track o is secured for the guide to travel in. At the top of the gate, the 1/2-in. channels are carried up each side of the frieze grille of the car, as shown at b in Fig. 3a, and also in Fig. 3b, where the lower bar of the frieze grille is shown at g and the side bars or channels at p.”

This description reveals the operational elegance of the Bostwick gate. Its visual elegance is seen in a 1902 advertisement for an elevator gate manufactured by William R. Pitt Composite Iron Works (Figure 4).

By the early 20th century, the name “Bostwick” was synonymous with sliding, collapsible metal elevator gates. Although other similar gate systems were manufactured in the U.S. and Europe, they were almost always commonly referred to as “Bostwick gates,” regardless of their brand name.

A phrase often heard when people encounter a simple solution to a challenging problem is, “Why didn’t I think of that?” However, as Walter Bostwick effectively demonstrated, sometimes genius lies not in having the idea yourself, but in recognizing a good idea when you see it.

- Figure 1: James E.Q. Maddox, “Improvement in Gates,” U.S. Patent 191,984 (June 12, 1877)

- Figure 2: Maddox and George P. Humphries, “Improvement in Gates,” U.S. Patent 213,119 (March 11, 1879)

- Figure 3: Bostwick-style gate technical drawings, Ornamental Ironwork, Colliery Engineer Co. (1899)

- Figure 4: “Bostwick Elevator Gate,” American Architect and Building News (October 4, 1902)

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.