The First Ocean Liner Passenger Lift

Mar 3, 2025

A popular symbol of modernity and cutting-edge transportation technology

The introduction of the electric lift in the late 19th century, coupled with the rapid expansion of the use of electricity into all phases of contemporary life, resulted in the creation of new venues for passenger lifts. One such venue was the ocean liner, which, by the early 20th century, had become a popular symbol of modernity and cutting-edge transportation technology. The challenges associated with utilising passenger lifts aboard large ships was summarised by R.A. Fletcher in 1913: “When it was first proposed to install lifts in ocean liners the objection was raised that the lifts would only work when their shafts were in a vertical position, and that otherwise the cages would jamb.”[1] Fletcher was the editor of the shipping section of the Magazine of Commerce and British Exporter, and the author of a series of books on naval history: Steamships, the Story of Their Development to the Present Day (1910), Warships and Their Story (1911) and Guide to the Mercantile Marine (1912). Thus, he was well positioned to provide insights into the introduction of passenger lifts into naval settings.

Apparently, his knowledge also extended into the activities of lift manufacturers, as was evident in his reported response to the concern about non-vertical shafts at-sea:

“But the makers tested the shafts they proposed to use for ships by running a cage up and down one inclined at various angles and also rocking as it would in a rolling ship, and it was found that the motion made no difference.”[1]

This description raises numerous questions about R&D practices in the early 20th century, as well as which companies were conducting these tests. Fletcher concluded his introduction to this topic by noting that:

“The Germans, with their usual enterprise, were the first to try whether the advantages of lifts at sea would be as great as was expected if the difficulty of the motion of the ship could be overcome.”[1]

In this instance, “the Germans” were represented by the Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Actien-Gesellschaft, more commonly known as the Hamburg-American Line. The building of the first ship to employ a passenger lift also illustrated the international character of this business sector, which, in this instance, did not, in fact, include the German lift industry.

The first ocean liner to feature a passenger lift was the SS Amerika, which was built in Belfast by Harland & Wolff. The lift manufacturer was R. Waygood & Co., Ltd. The ship was launched on 20 April 1905, and its maiden voyage began on 11 October 1905 (Hamburg-Dover-Cherbourg-New York). In March 1906, The Engineer published a two-part article titled “Electricity on Atlantic Liners.” Part two of the article included a detailed, illustrated account of Waygood’s passenger lift.[2] In October 1906, The Steamship also featured an illustrated article on the Amerika’s passenger lift.[3]

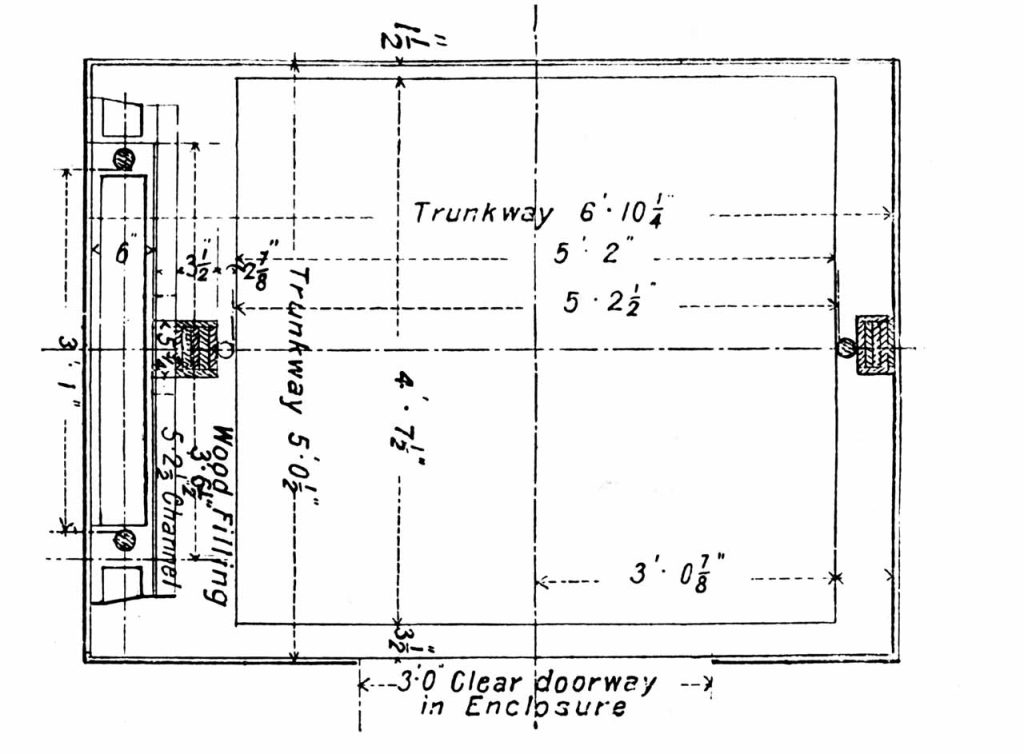

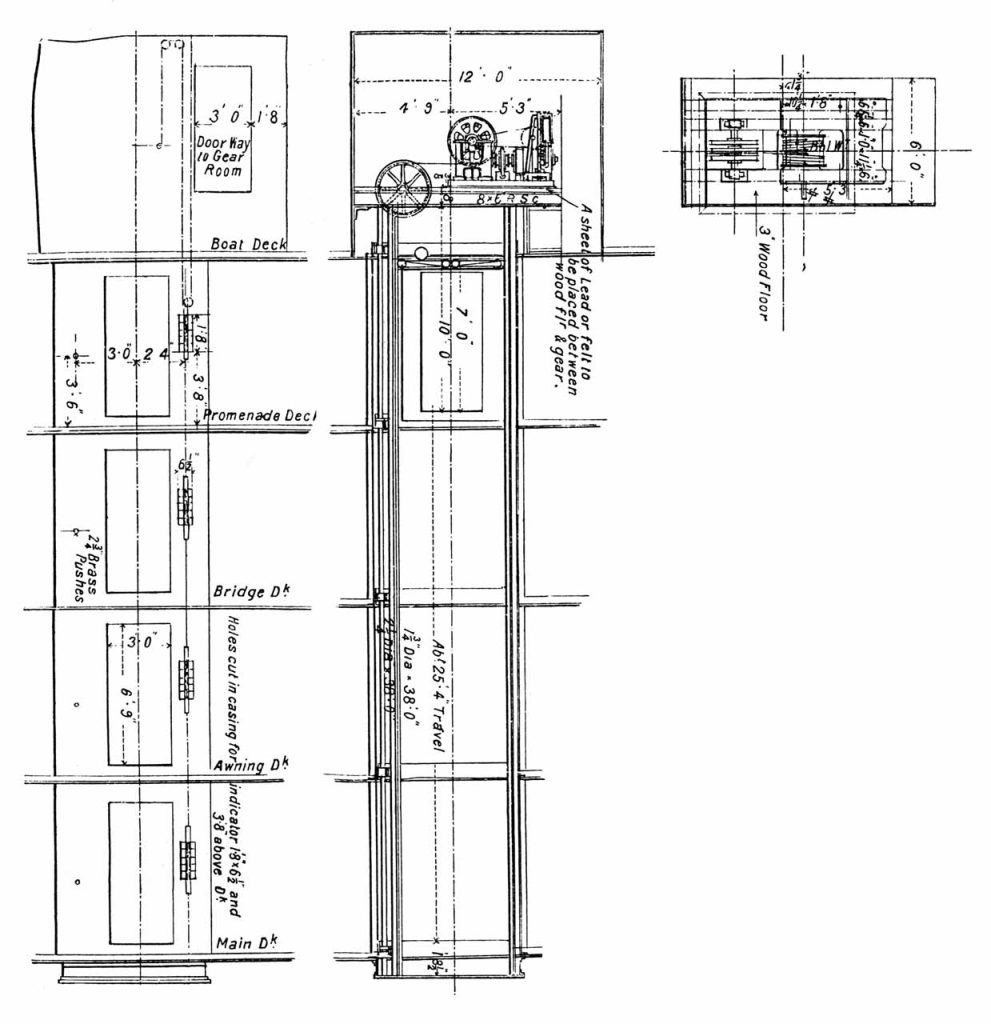

The lift’s capacity was listed as 10 cwt. (approximately 500 kg), which allowed for seven riders — the operator plus six passengers. The travel distance was 35 ft, 5 in. (approximately 11 m), and the lift served four decks: the Main or Cleveland deck, the Awning or Roosevelt deck, the Bridge or Washington deck and the Promenade or Kaiser deck. The machine room was located on the Boat deck (Figure 1).

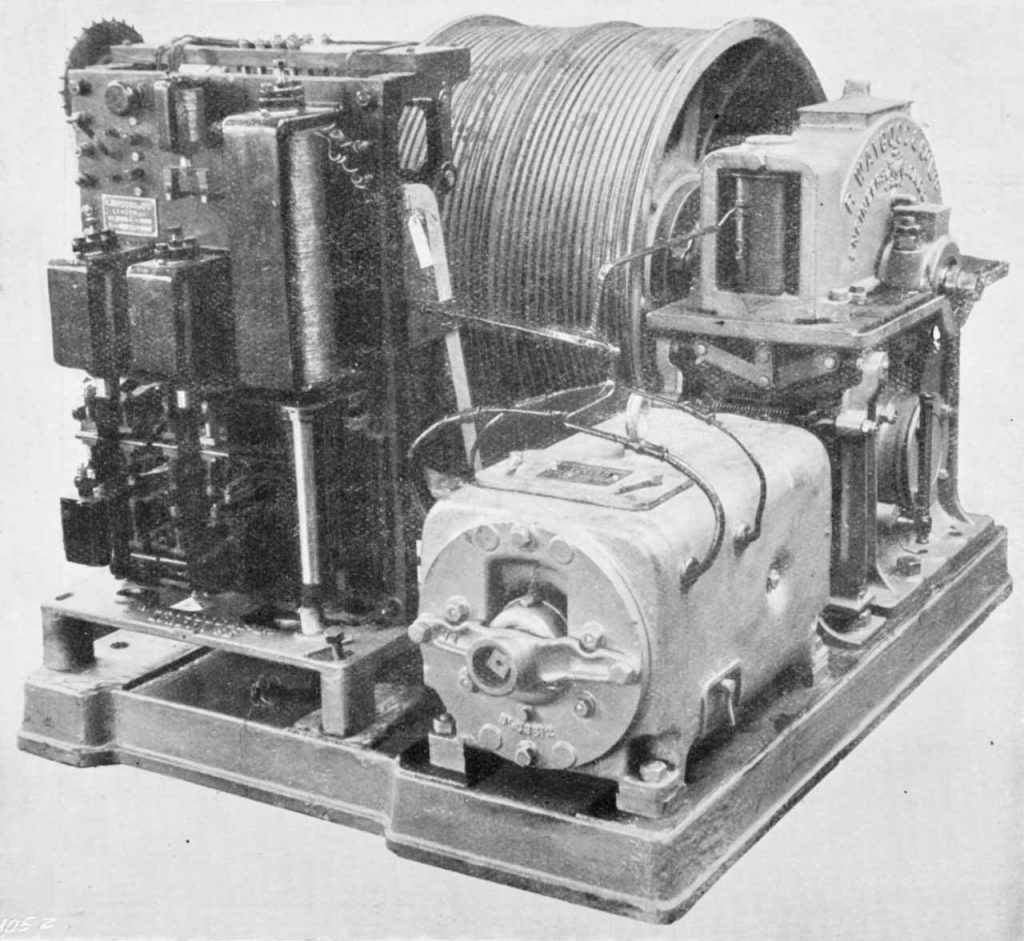

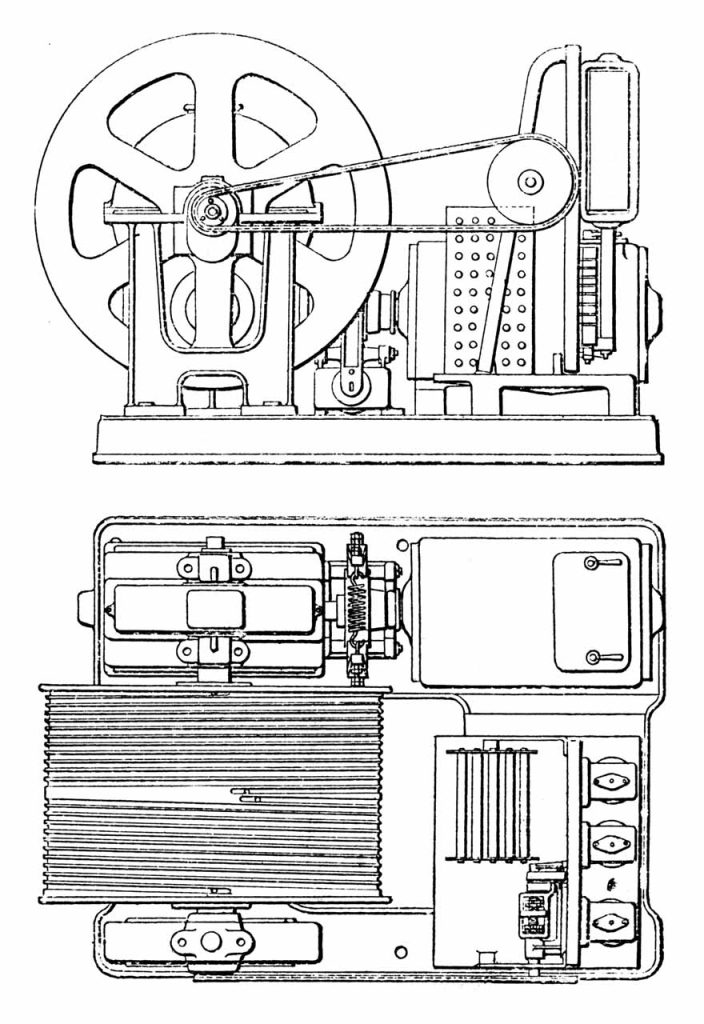

Although the confined shipboard space allowed for a full machine room, the drawings appear to indicate that the pit depth was limited to 20.5 in. (approximately 0.5 m). The machine room housed a remarkably compact lift machine, which featured all of the components mounted on a single bedplate (Figure 2). Although no photograph of the Amerika lift machine has been found, a photograph of a Waygood machine installed aboard the RMS Mauretania in 1907 illustrates the compact nature of the machine’s design (Figure 3).

The machine was equipped with a shunt-wound, enclosed-type Siemens’ motor, which was “rated at 7 brake horsepower when running at about 900 revolutions per minute, although the (typical) actual duty (was) only about 5 brake horsepower.”[2] The winding drum was directly connected to the motor’s armature via a steel worm, which geared:

“with a machine-cut worm wheel, with phosphor bronze rim and teeth built up upon a cast iron centre. The gear works in a cast iron casing, which forms an oil bath, the worm being arranged beneath the wheel so as to be always submerged in oil. The thrust of the worm shaft is taken by adjustable double-ball thrust bearings, which are easily accessible from the outside, and in this respect, it is claimed that they have a considerable superiority over the ordinary marine type of bearings, which necessitate dismantling the machine when they have to be renewed. The worm wheel shaft carries a cast iron winding drum, which is turned in grooves to suit the steel wire lifting ropes. Two ropes are positively attached to the drum and connected to the cage, and two independent ropes are attached to the drum and connected to the balance weight, so that one set of ropes coils on the drum as the other coils off, the drive in this case being positive and not depending upon friction. An outer bearing is provided to take the end of the drum shaft.”[2]

The machine employed an electro-mechanical brake, which acted on the motor coupling. Overwinding was:

“guarded against by a special automatic cut-off arrangement, consisting of a sprocket wheel on the drum, which drives by means of a chain on to a wheel on the controller, which is arranged so that when the drum has made a fixed number of revolutions in either direction a limit switch is opened on the controller itself; this shuts off the current and applies the brake and the lift is gently brought to a standstill.”[2]

The machine was also equipped with Waygood’s patented slack cable safety switch. The switch was placed in “connection with the cage and balance weight by a safety rope, so that if the cage or balance weight meets with an obstruction … a no-voltage cut-out is operated, and the motor is at once brought to a standstill.”[2] Another safety device, located beneath the car, consisted of four serrated cams that were “held out of action by suitable springs.”[2] An “independent safety rope” was “connected direct on to the cams, so that in case of failure of the suspension ropes, the weight coming on to the safety rope brings the four cams into action; these grip on the runners provided and arrest the descent of the cage.”[2]

The car ran on “round turned steel” guides, which were designed to “give the greatest smoothness of running,” and which were “fitted to laminated timber backings on which the safety gear would grip in case of failure of the ropes” (Figure 4).[2] The counterweight also ran on round steel guides, which were “fixed to the ironwork of the ship.”[2] Although, as was recounted by Fletcher, Ocean Liner lifts were found to be able to operate in heavy seas without problems, Waygood included an extra safety feature on the Amerika lift to address this concern:

“In order to prevent the possibility of the cage leaving the guides, in case of the ship rolling at an acute angle, additional safety guides of planed angle iron are fixed at opposite corners of the cage, so that it runs just clear of these guides under ordinary conditions.”[2]

Unfortunately, the published drawings do not illustrate the precise location or nature of these safety guides. While the provision of this additional safety was doubtless due to the fact that this lift was the first to be installed on an ocean liner, the account of the lift’s operation reveals that these additional safeties were unnecessary:

“It was found, however, that on the first voyage, although the ship encountered some heavy weather, there was no defect at all in this respect, and the only effect upon the lift was that the current consumption was increased slightly — not more than about 2.5 A — under the most severe conditions when the ship was rolling.” [2]

Interestingly, the presence of a final safety device was apparently dictated, not by standard U.K. lift industry practices, but by a foreign government:

“In accordance with the regulations of the German Government, interlocking arrangements are provided in connection with the doors on the different decks, so as to prevent either door being opened except when the cage is opposite it, and to prevent the lift being started away unless all the doors are properly closed.”[2]

Germany was one of the first countries to develop national lift safety regulations and, given that the Amerika was built under the direction of a German company, it made sense for the lift to comply with applicable German laws. While interlocks were a common feature on U.K. lifts, this raises the question of whether Waygood would have installed interlocks if they had not been required.

Thus far, no image of the Amerika lift installation has been found; however, its general character may be assessed in a photograph of the lifts installed aboard the RMS Mauretania in 1907 (Figure 5). The Amerika lift car was designed “to correspond with the saloon fittings,” and was made of mahogany, decorated in white enamel and included a bench seat and beveled mirrors.[2] Push call buttons were provided on each landing, as well as indicators showing the lift’s location. The car also featured a button that could be used to ring the engine room in the event of an emergency. The operator controlled the lift by a typical switch, which featured three positions: “up,” “down” and “stop.” When released, the switch automatically returned to the center or “off” position. The handle was also removable, which prevented “anyone from interfering with the lift” in the operator’s absence. During the Amerika’s maiden voyage, the lift made 2,154 trips and carried 4,469 passengers.[2]

In his 1913 book, Fletcher outlined the speed with which passenger lifts became standard features on North Atlantic ocean liners. However, while these ships were the primary focus of the popular press and formed the core of public awareness of this dynamic transportation system, as was noted by Fletcher, these ships were not the only ones to introduce passenger lifts during this period:

“Lifts are not confined to steamers of the North Atlantic. The splendid ‘A’ steamers of the Royal Mail Steam Packet (RMSP) Co., and the newest vessels of its associated lines, the Pacific Steam Navigation Co. and Messrs. Lamport and Holt, have introduced them to the South Atlantic and the Pacific. The P.&O. Co., by installing lifts in its latest ‘M’ class steamers, has familiarised them to travelers to and from India, Australia and the Far East; and voyagers to and from Australia thoroughly appreciate the convenience in all the new steamers of the Orient line. The Allan line has placed lifts in its new steamers Calgarian and Alsatian; its great rival in the Canadian trade, the Canadian Pacific Railway Co., deemed its new steamers the Empress of Russia and Empress of Asia incomplete without lifts; they are also to be included in a new steamer which is under construction for the Union Castle line’s South African trade, this, perhaps, being one result of the company coming under the control of the enterprising RMSP. Nor are the colonial steamship services behind the great companies of the old world in their endeavours to add to the comfort of their patrons. The Union Steamship Company of New Zealand is having them fitted in the Niagara, while two of the great Australian shipping organisations, the Howard Smith line and the Australasian United Steam Navigation Co., are following suit in the Canbera and Indarra respectively.” [1]

Thus, the adoption of electric passenger lifts on ocean liners between 1905 and 1913 may have played an important and unexpected role in introducing this new lift type to a global audience — perhaps, in fact, far more rapidly than its adoption in standard building construction.

References

[1] R.A. Fletcher, Travelling Palaces: Luxury in Passenger Steamships, London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, Ltd. (1913)

[2] “Electricity on Atlantic Liners, No II,” The Engineer (30 March 1906).

[3] “Waygood Passenger Lifts on Ocean Liners,” The Steamship (October 1906).

[4] The Cunard Turbine-Driven Quadruple-Screw Atlantic Liner “Mauretania,” Reprinted from Engineering, London (1907).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.