The History of Operatorless Elevators: Push Button Control 1886 -1895

Apr 6, 2023

Period established a critical baseline for all future work.

The story of the invention of the operatorless elevator encompasses the history of several discrete vertical-transportation (VT) systems. The first to be developed was a new type of control system that simplified elevator operation such that a trained operator was no longer required. As was the case with numerous elevator technologies, the system adopted — and adapted — for elevator use was not initially intended for this purpose. The history of the push button switch embraces a variety of issues and uses, as well as changing attitudes toward modernity, exemplified by a gradual shift to a world where an array of services was suddenly available “at the press of a button.”[1] Although push button switches existed prior to 1880, this date is typically identified as marking the introduction of the electric push button.

One of the first inventors to propose an electric push button control system for elevators was Boston engineer John H. Clark. In August 1886, Clark filed a patent application with a deceptively clear title: “Electric Elevator.” However, the patent, awarded in November, concerned a hydraulic elevator whose operation was controlled by two electric push buttons (Figure 1). The phrase “electric elevator” was apparently chosen to highlight the replacement of an outdated system with the latest technology:

“Prior to my invention the power-controlling valve has been operated by means of a shipper-rope passed about sheaves fixed to the building and about a sheave on a shaft or rod, operatively connected to the power-controlling valve … (this) arrangement being especially objectionable on account of its unsightliness and on account of the power required to move it.”[2]

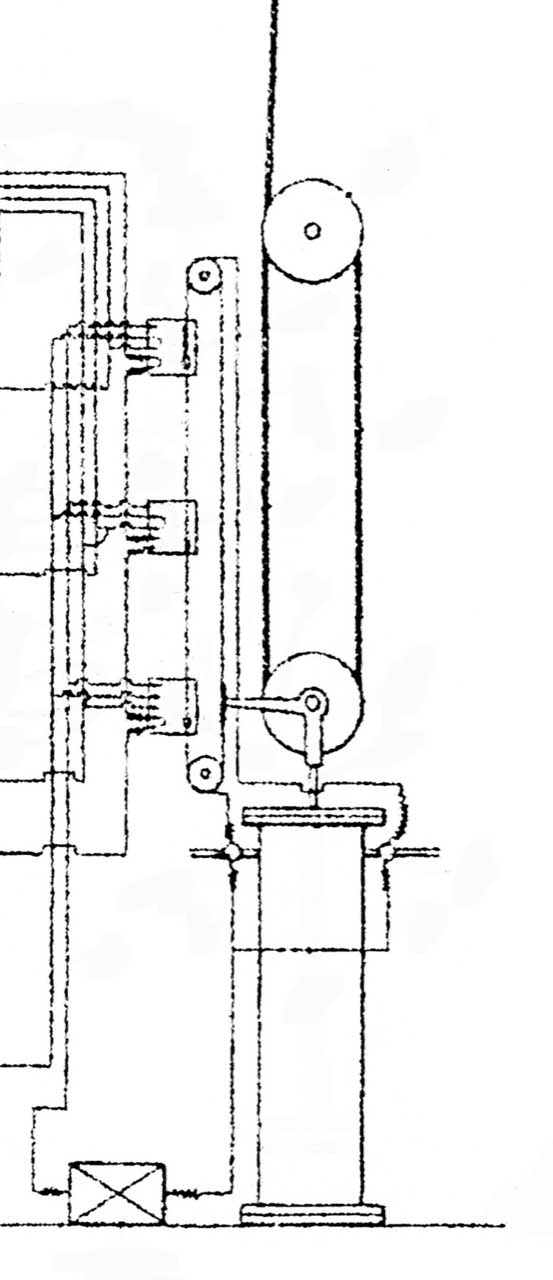

Clark provided two buttons in the car, one of which caused the car to ascend, the other to descend. While the user did have control of the elevator with the push of a button, its actual operation was slightly more complicated. To ascend, the proper button was pushed to initiate upward movement. In order to sustain the car’s movement, the operator was required to maintain constant pressure on the button until the car reached its destination, at which point the button was released and the car stopped. Clark filed a second patent application in May 1887 for a variation on his original design (Interestingly, this patent was not awarded until 1898).[3] The patent was assigned to the Whittier Machine Company (Boston); however, it is unknown if Whittier built any machines that featured Clark’s push button system.

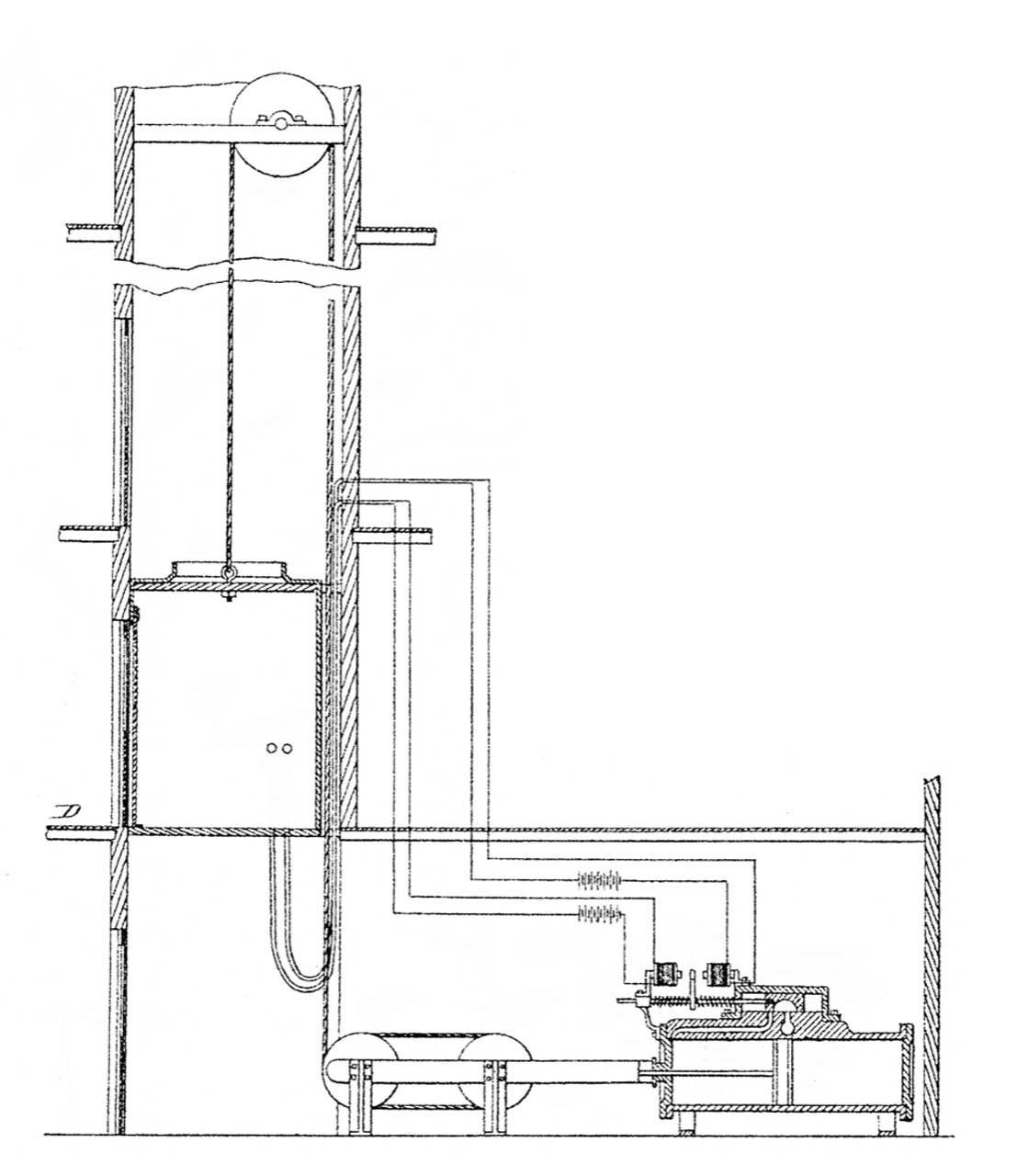

In November 1887, New York engineer Charles E. Ongley filed three related patent applications for an “electrically-controlled elevator.” Two additional related applications were filed in July and April 1888, and all five patents were awarded in September 1889.[4] Ongley’s system paralleled Clark’s in its application to hydraulic elevators and in its basic operation, which required the operator to sustain pressure on a button while driving the car. Its importance to this story is that all five patents were assigned to the Hydraulic Elevator Company of Chicago, which had been established by Otis Brothers in 1878. The company, founded in conjunction with Otis’ acquisition of William E. Hale & Co., was created as a holding company for existing and future patents associated with Hale’s duplex hydraulic elevator system.[5] Thus, Ongley’s patents marked Otis’ initial foray — via a proxy — into the design of push button control systems. His patent drawings also effectively illustrated the dichotomy between the architectural imagery of the late 19th century and the emerging modern era of push button control (Figure 2).

In May 1891, Andrew M. Coyle, of Washington, D.C., filed a patent application that continued the trend established by Clark and Ongley; he also proposed to utilize an electric push button system to control a hydraulic elevator.[6] However, Coyle’s design included several improvements over the prior schemes. The most significant improvement was a new button design, which required only a single push to activate and sustain the elevator’s movement:

“All the desired movements of the car can be effected safely and with certainty without the exercise of any more care and intelligence than is required to touch a button corresponding to the number of the floor to which the car is desired to move … when one of the switches or push-buttons is actuated the car will move to and come to rest at that floor, no matter whether the car be above or below the floor. This arrangement has obvious advantages over that which requires one operation to cause the elevator to ascend and another to cause it to descend.”[6]

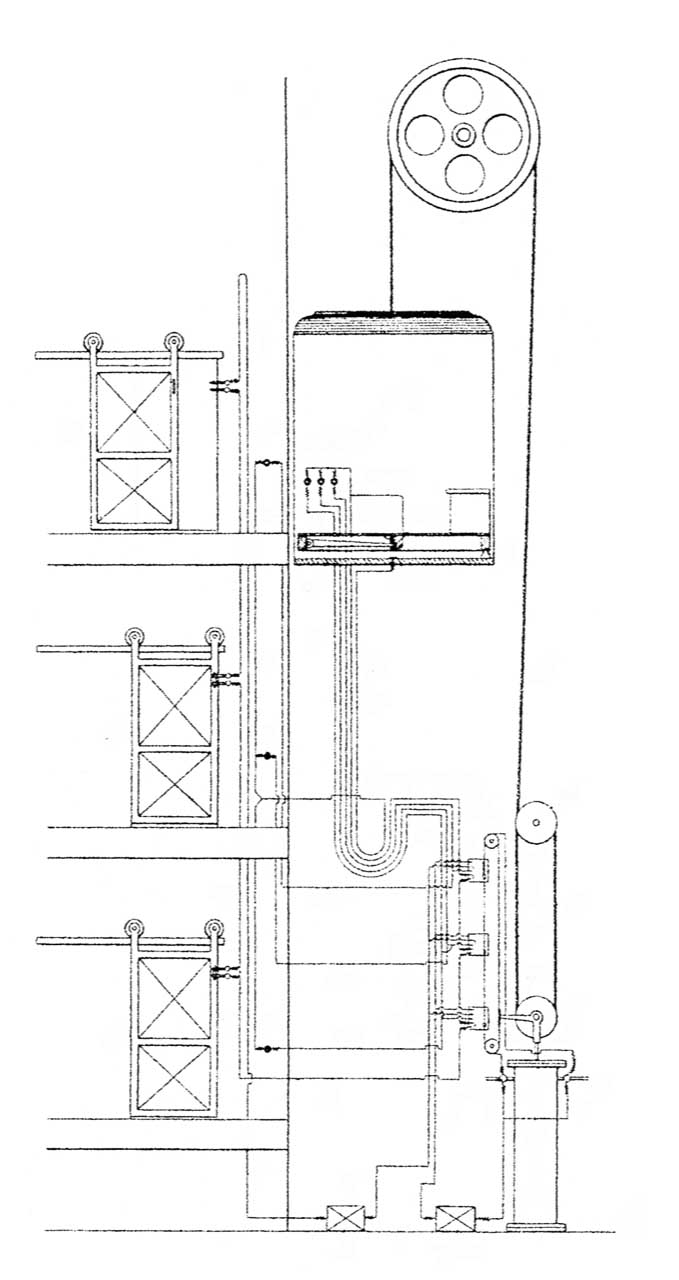

The car was equipped with one button for each floor and, for the first time, each landing was provided with an elevator call button (Figure 3).

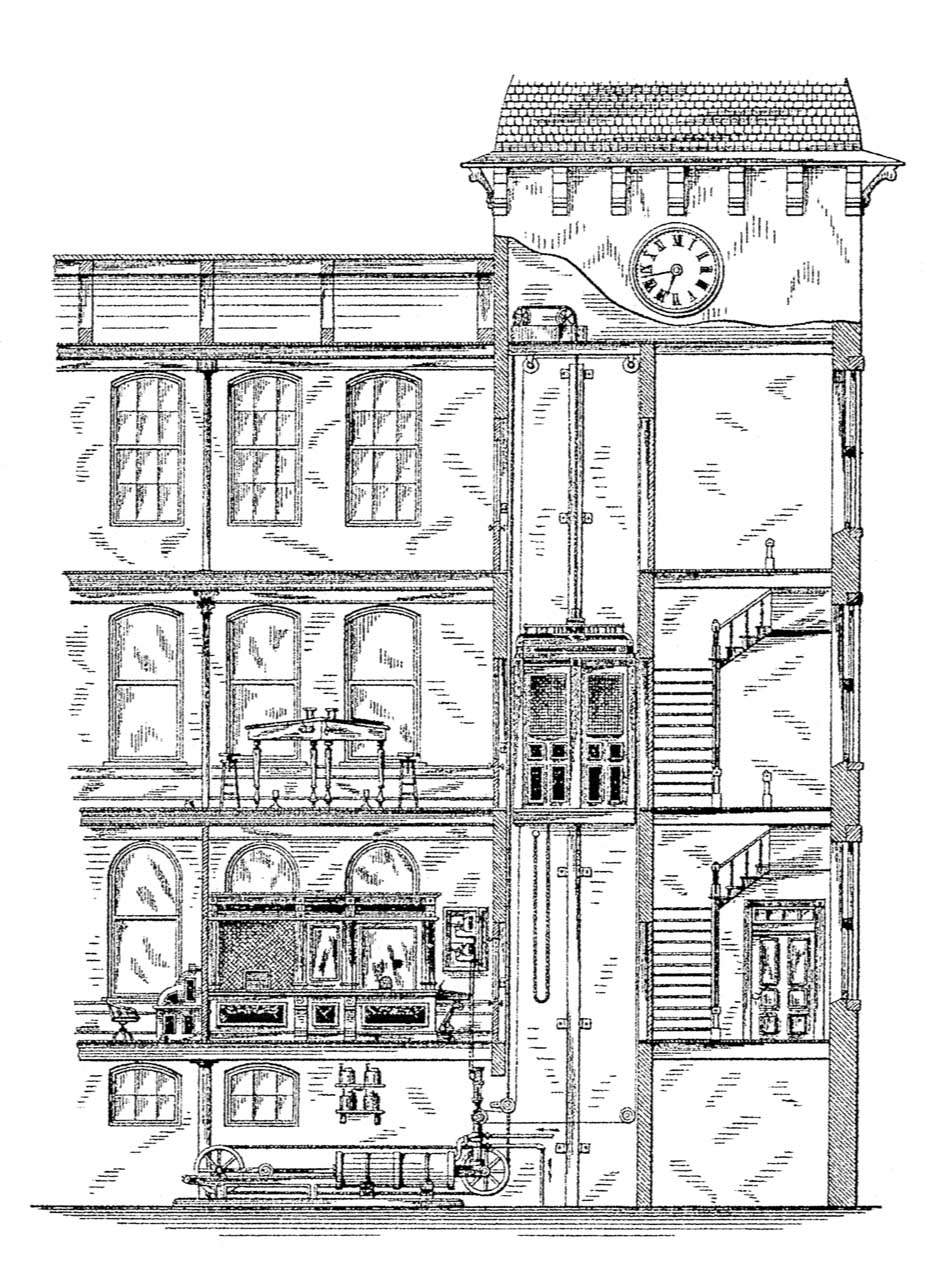

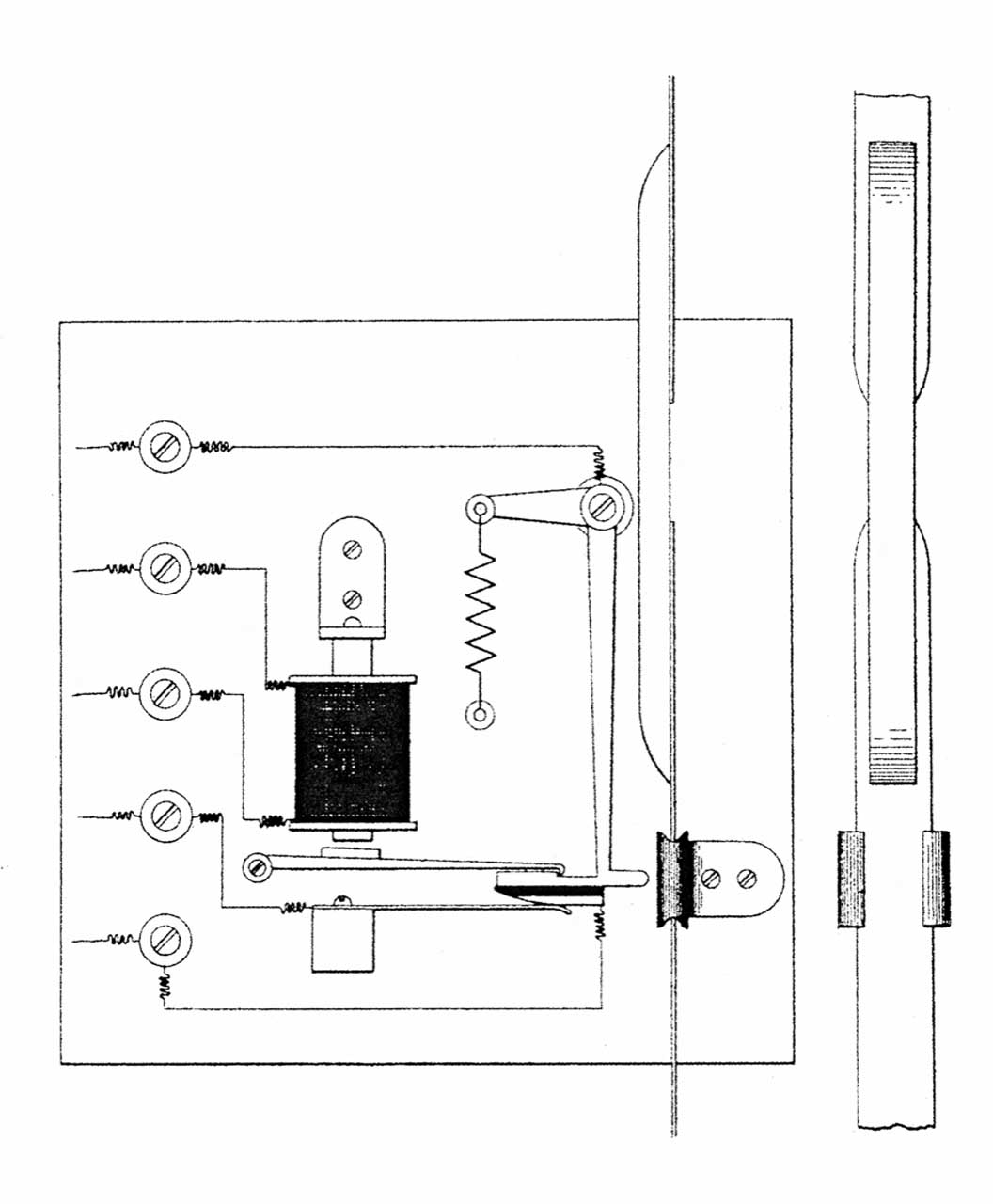

The system that automatically stopped the car at the landings employed an endless metal band that was connected to the hydraulic engine’s vertical piston such that it traveled “in unison with the car, but over a smaller path.”[6] The band was connected to the electric circuit that operated the hydraulic valves. As it moved, it passed through a series of “switch-boards,” each of which was provided with a “main-circuit closing mechanism.”[6] The switch-boards (one for each floor) were set “at distances apart corresponding to the distance between the landings.”[6] The endless band was equipped with an elongated cam that, when it reached the switch-board of the destination floor, opened the main-circuit closing mechanism and stopped the car’s movement (Figures 4 and 5).

A unique safety device was also incorporated into the design. The elevator featured a floor-switch that was activated when a passenger entered the car. The activation of this switch by the passenger’s weight prevented the operation of the landing switches such that, according to Coyle: “No one at any of the floors can control the movement of the car so long as the same is occupied.”[6] While this patent introduced several important design elements, including designated floor buttons in the car, hall-call buttons and an automatic landing system, its use was essentially limited to one passenger or one group of passengers at a time (due to the action of the car-floor-switch). This limitation was a direct result of Coyle’s electrical system design, which, as was the case with other contemporary schemes, reflected the fact that circuit design was still in its relative infancy.

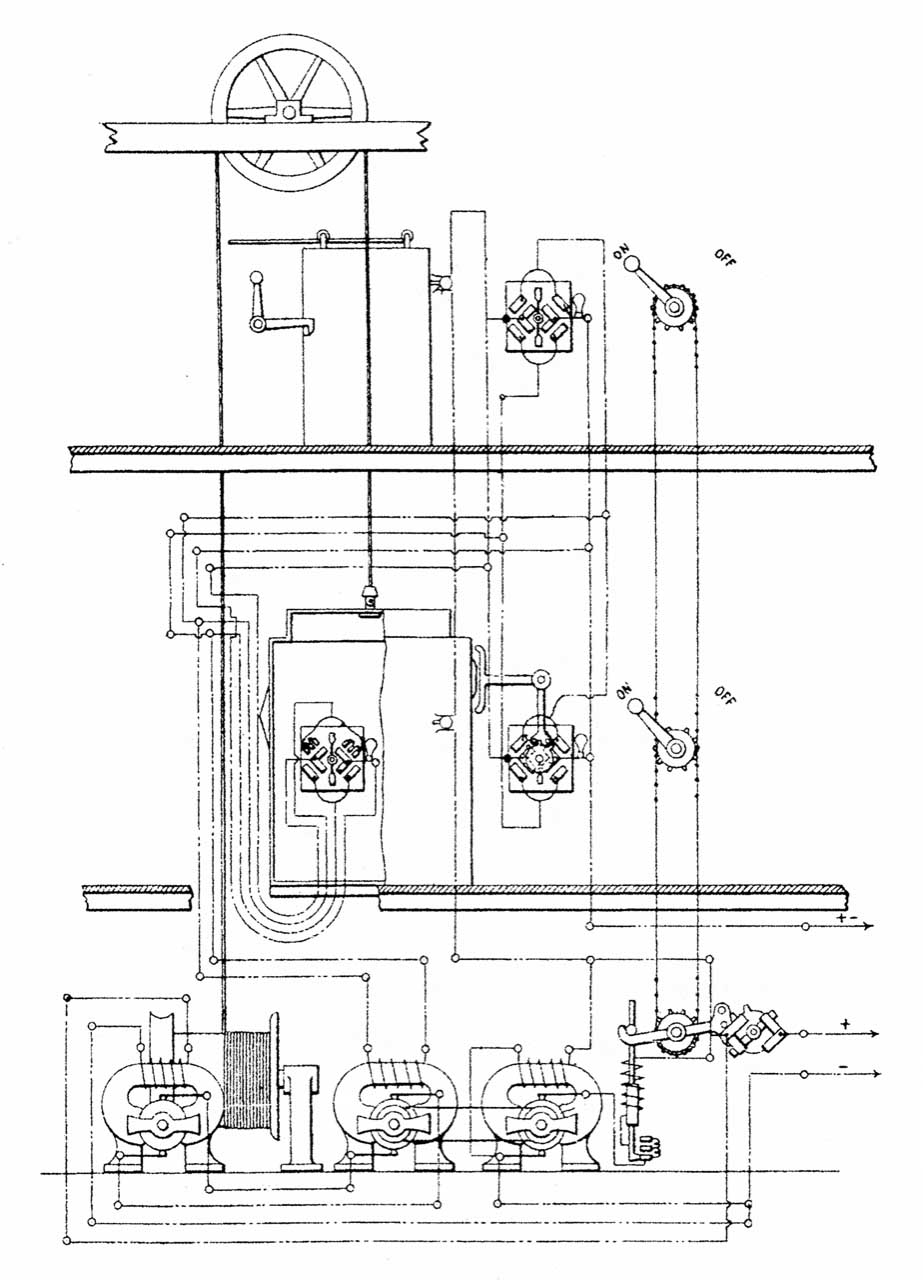

In April 1892, Otis officially entered the race to develop a push button control system: Norton P. Otis & Rudolph C. Smith filed a patent application for the first system applied to an electric elevator: Controlling Device for Electric Elevators (awarded in April 1898).[7] Otis and Smith’s design incorporated features found in earlier designs and employed a recently patented motor control system:

“Our invention relates to automatic circuit controlling devices for electric elevators, and has more particular relation to such controlling devices when used in connection with what is generally termed the ‘Leonard’ system of transmission of power; and it has for its object to adapt said system for the operation of elevators, whereby they may be safely and economically operated and whereby the circuits may be controlled from the car or from the various floors or landings of the building … so that the whole system may be stopped, started, and controlled either from the car or from any of the landings … The so-called ‘Leonard’ system of transmission of power … consists, generally stated, in the combination of an electric motor which is connected to apply the power to the car … and is known as the ‘working’ motor, an intermediate motor, and an intermediate generator driven by said intermediate motor and connected with the working motor.”[7]

Otis’ pioneering use of what eventually became known as Ward Leonard control placed them at the vanguard of electric elevator motor design.[8] However, their proposed push button control system was decidedly less sophisticated.

At the landings, the control system consisted of a large power-switch-lever, a small knife-edge switch used to turn on the power to the landing switch, and a push button used to call the car (Figure 6). Each landing also featured a system designed to automatically stop the car: A cam on the side of the car operated a switch-lever that was connected to a landing switch. Although Otis and Smith stated that “the whole system may be stopped, started, and controlled … from the car,” their description of the car operating system was somewhat schematic. While the car was described as also having a knife-edge switch to turn on the power, the description did not include any mention of a push button and it is unclear how the operator controlled the car’s movement (up or down). Nonetheless, this patent was the first to link the electric push button with the electric elevator.

Cyprien O. Mailloux closed the first phase in the development of push button control systems with two patent applications: one filed in December 1894 and the other in May 1895 (both patents were awarded in 1895).[9, 10] Mailloux had filed a patent application in July 1890 for a push button system; however, his application was held up in the approval process for such a lengthy period that he finally decided to divide the original application and file a new one in August 1899. The revised application referred solely to the designs found in his 1895 patents, thus his 1890 design was lost. The loss of the original patent is significant given the fact that Mailloux was one of the leading electrical engineers of the late 19th century. He was a charter member of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers (AIEE), served as an editor of Electrical World magazine and had a prolific career as a consulting engineer. He earned more than 30 patents, four of which concerned elevator control systems.

Mailloux’s rationale for his design, expressed in his April 1895 patent, addressed two fundamental issues, the first of which echoed the aims of earlier designers:

“My invention has reference to electrical means for controlling the direction of motion of elevator cars or lifts for passenger or freight purposes and especially to the adaptation of such means to elevators intended to be operated by unskilled persons. Said invention is especially applicable to elevators in private residences where it is desirable to operate the elevator car from within or from without at any floor or story. The main object of my invention is to secure greater safety and convenience in operating an elevator and to obviate interference in case several individuals attempt to operate the elevator simultaneously in the same or in opposite directions from different floors.”[9]

His second rationale focused on the overall electrical design of the push button system:

“Another object of my invention is to do away with the relatively heavy currents in the circuits used for controlling the machinery, and to make use of smaller currents more like those used in telegraphy, whereby the relatively bulky and obtrusive switches may be replaced by simple push buttons or small switches which are less objectionable in furnished and ornamented interiors, in private residences, club houses and the like.”[9]

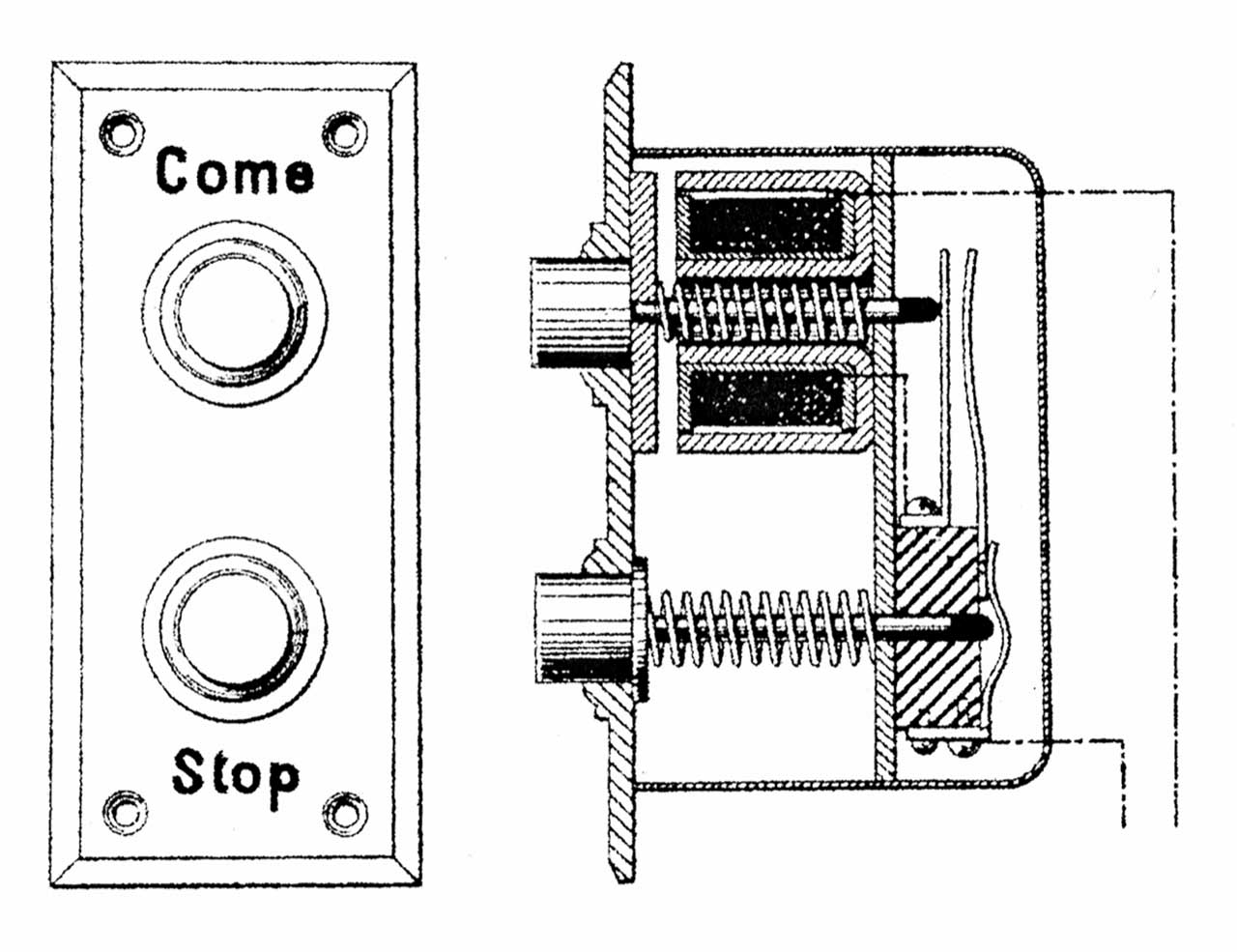

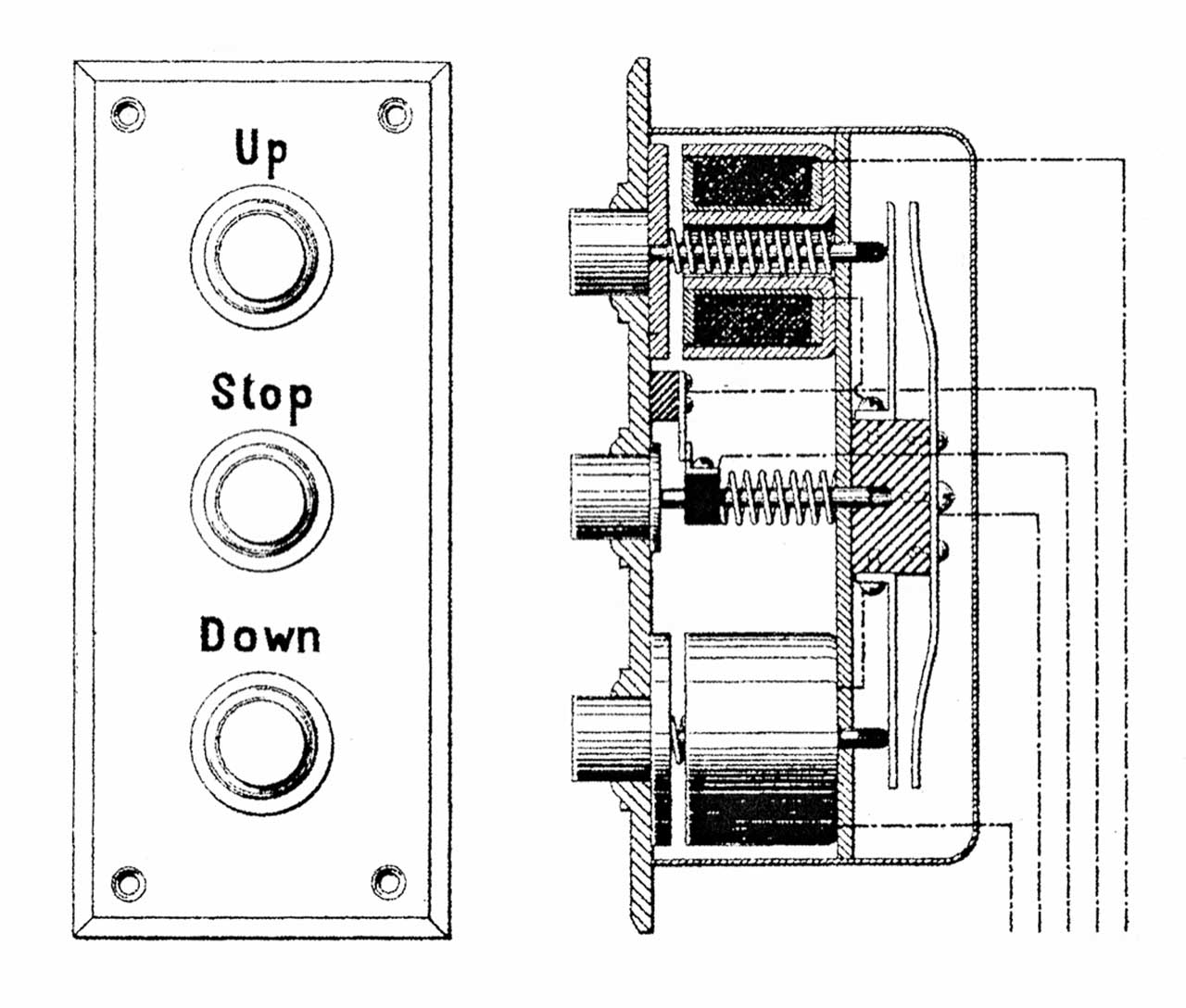

As was the case with Coyle’s design, Mailloux’s push buttons, which he referred to “self-holding,” required only one push to activate the system. His patent included a variety of button systems, including a two-button hall-call system and a three-button car system. The hall system featured a call button labeled “come” and a “stop” button (Figure 7). The waiting passenger used the “come” button to summon the car and the “stop” button when the car was level with the landing. The car buttons were labeled “up,” “down” and “stop” and functioned in a similar manner (Figure 8). He also provided a design for a “floor switch,” located on the exterior of the car, which would automatically stop the car at its destination. He claimed that his control system was applicable to electric, hydraulic or steam powered elevators.

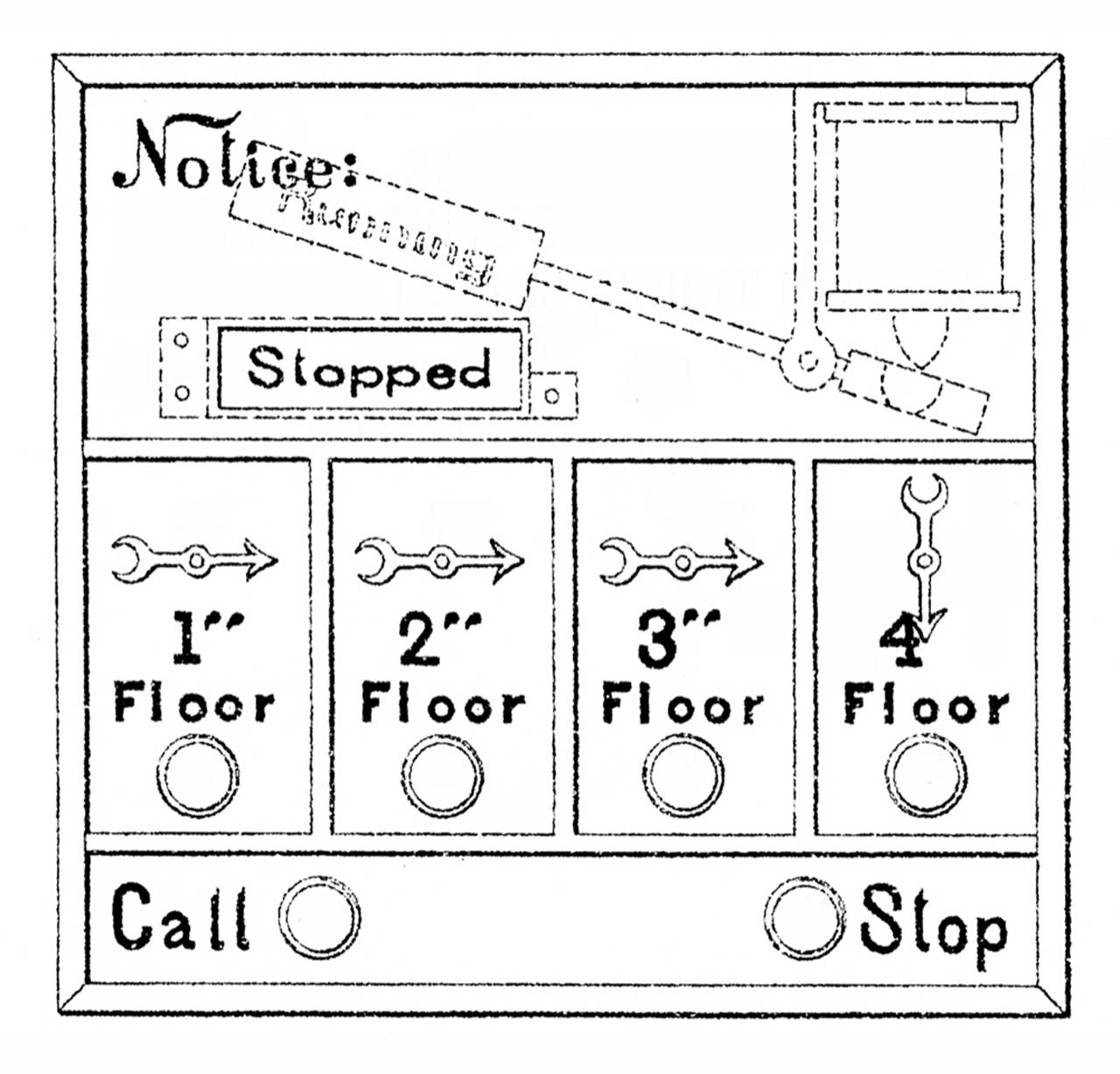

Mailloux’s July 1895 patent focused on refinements to the systems found in his April patent and included a new hall system that featured individual floor buttons. The hall floor-buttons were housed in a panel that featured “annunciator-arrows” above each button, a panel that displayed a sign indicating that the car was either “stopped” or “running,” and a “notice board.”[10] Mailloux intended that each notice board would feature the same message: “The machine will not work unless all landing-doors are closed.”[10] The annunciator-arrows were designed to pivot downward and indicate where the car had stopped and that a shaft door was open (Figure 9). Thus, the arrows gave waiting passengers the opportunity to track the elevator’s movement. Additionally, if an arrow remained in a downward position for a long period of time — indicating that a passenger had left the car and had failed to close the door — a waiting passenger could push the designated floor button, which would send an alarm signal to the landing where the car had stopped.

The period from 1886 to 1895 marked the initial phase in the development of electric push button control systems. Although further refinements were clearly needed and would be developed in the coming years, this period established a critical baseline for all future work. An upcoming article will continue this examination of the history of the VT industry’s pursuit of the operatorless elevator.

References

[1] Rachel Plotnick, Power Button: A history of pleasure, panic and the politics of pushing, MIT Press (2018).

[2] John H. Clark, Electric Elevator, US Patent No. 353,123 (November 23, 1886).

[3] John H. Clark, Elevator, US Patent No. 609,533 (August 23, 1898).

[4] Charles E. Ongley: Electrically-Controlled Elevator, US Patent No. 410,180 (September 3, 1889), Elevator, US Patent No. 410,181 (September 3, 1889), Electrically-Controlled Elevator, US Patent No. 410,182 (September 3, 1889) (April 18, 1888), Electrically-Controlled Elevator, US Patent No. 410,183 (September 3, 1889), and Electrically-Controlled Elevator, US Patent No.410,184 (September 3, 1889).

[5] Lee E. Gray, From Ascending Rooms to Express Elevators, Elevator World (2002).

[6] Andrew M. Coyle, Electrically-Controlled Elevator, US Patent No. 471,100 (March 22, 1892).

[7] Norton P. Otis & Rudolph C. Smith, Controlling Device for Electric Elevators, US Patent No. 610,197 (September 6, 1898).

[8] Howard Ward Leonard, Electrical Transmission of Power, US Patent No. 463,809 (November 24, 1891).

[9] Cyprien O. Mailloux, Electrical Controlling System for Elevators, US Patent No. 536,730 (April 2, 1895).

[10] Cyprien O. Mailloux, Electrical Controlling System for Elevators, US Patent No. 543,495 (July 30, 1895).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.