The Invalid Lift, Part Two

Jan 1, 2019

The conclusion of a series on early elevators for handicapped persons begins with the early 20th century.

The invalid lift, a hand-powered elevator system introduced in the mid 1800s, was designed for use in residential settings by persons with disabilities (ELEVATOR WORLD, December 2018). By the end of the 19th century, numerous elevator and dumbwaiter manufacturers marketed these lifts, and they remained in production throughout the first decades of the 20th century. One of the leading invalid lift manufacturers during this period was Sedgwick Machine Works of New York. It began manufacturing dumbwaiters and hand-powered elevators in the early 1890s. By 1900, it offered customers two invalid lift systems: one equipped with a brake controlled by the passenger and one equipped with an automatic brake.

The first system employed a hand brake operated by a “brake line” that extended the length of the shaft and was accessible from the car. To move the car, the passenger first pulled up on the brake line. This action partially released the brake and allowed the passenger to move the car up or down by using one of the hand ropes flanking the shaft. When the passenger reached their destination, they pulled down on the brake line to lock the brake and hold the car safely in position. This system was featured in Sedgwick’s first invalid lift drawings, both of which depicted young women operating the lift (Figures 1 and 2). Their other system employed an automatic brake linked to the use of the hand ropes, such that when the passenger began to pull on one of the ropes, the brake automatically released. Both systems were described as “safely counterweighted so as to balance both car and passenger.”[1]

Sedgwick emphasized its elevator’s ease of operation in advertisements and catalogs. A1912 advertisement included a letter from a “satisfied customer” that highlighted this attribute:

“In my house, we had no elevator, and my daughter had to depend on our man to carry her up and down stairs. If she wished to let the man have an evening off, she had to go upstairs right after supper and stay there. Now. . . she is entirely independent, goes up and down by herself, can run the elevator with one hand, and she goes up and down as often as she wishes and when she wants to. The elevator is a great comfort to us, and we shall be glad to have anyone needing such a thing come and see it or write us about it. There are many invalid ladies and men who toil laboriously upstairs, who, if they knew of the Sedgwick Hand Power Elevator, would not be without one.”[2]

The letter’s author was identified as a “well known New England Judge” who had installed the invalid lift in his home in 1907. A 1919 article on Sedgewick’s invalid lifts offered a rationale for the use of these elevators and referenced the 1912 letter:

“Where there is an invalid in the home, it frequently occurs that the invalid must sleep downstairs, while all the rest of the family have their sleeping rooms on the upper floor, merely because the invalid cannot get up and down stairs. The installation of a Sedgwick Hand Power Invalid Elevator permits the invalid to have his own room among the other bedrooms of the family, which is not only a convenience to him but is a convenience to the rest, as well, because, frequently, it is not convenient to give up a downstairs room for use as a sleeping room ……… One of these Sedgwick Invalid Elevators was installed many years ago in the home of a New England judge whose daughter was confined to a wheelchair, and, when she desired to go up or down stairs, she had to be carried in the arms of a strong serving man. After the installation of the elevator, the young lady was able to operate the elevator herself, rolling the chair into the car of the elevator, operating the elevator herself and thus going about the house, upstairs and down, indoors and out, with freedom such as she had never known before.”[3]

The lift’s ease of operation was further highlighted by a second account, which reported that, in one household, the lift was successfully “powered” by a five-year- old boy, who reportedly “took great delight and felt very important in acting as elevator man to take his father up and down.”[3] This account served as the inspiration for a 1920 drawing of the Sedgwick Invalid Lift, which included the caption “This boy is having fun.” (Figure 3). The article’s unknown author also reported that still more evidence proving how easy these lifts were to operate existed:

“It was assumed that, when a five-year-old boy furnished the motive power for operating an elevator carrying himself and his father, who was a heavy man, both up and down, the limit had about been reached, but at the present time, the record is held by a southern Miss.”[3]

The “southern Miss” was a “little girl three years old, who weighs but thirty pounds” who was “able to lift her mother’s weight and her own to the second floor without undue effort.”[3]

While these accounts speak to the lift’s ease of operation, the prospect of young children operating these elevators raises numerous safety concerns. The presence in the Sedgwick illustrations of what appears to be a standard residential half- or Dutch-door also prompts other safety- related questions. (The catalog text made no mention of door interlocks). The half-door may have been intended as a type of safety system. If only the upper half of the door were open, a person on a lower or upper floor could pull on the hoist ropes and thus raise or lower the car, standing in a somewhat safer position than if they were adjacent to a completely open shaft.

As was the case in the 19th century, the early 20th century saw additional elevator companies enter the invalid lift market. In 1912 O’Neill Elevator Co. of Philadelphia announced production of the “O’Neill hand power invalid lift.” This was described as “suitable for private houses, hospitals, etc., where the amount of use does not warrant the expense of installing a power-driven lift.”[4] And, perhaps consciously copying Sedgwick’s promotional strategy, O’Neill proclaimed its lift was “fitted with all the latest improved safety devices, which makes it absolutely safe,” and they noted it could “be operated by a child.”[4]

In the second decade of the 20th century, George T. McLauthlin Co. of Boston published a series of mini- catalogs, labeled Bulletins, each of which was dedicated to one of its various elevator lines. Bulletin 113, Hand Elevators, included McLauthlin’s “standard type of hand-power passenger elevator or invalid lift.”[5] The description of the lift’s automatic braking system paralleled Sedgwick’s catalog copy:

“An automatic-lock brake controls the speed of the car. This brake or lock is self-supported and holds the car securely in position until operation of the hand rope in either direction moves it. The load cannot overhaul the machine and coast down, and the safety of the passengers is not dependent on the correct handling of a brake cord by the operator. The brake is absolutely automatic in operation and brings the car to rest without shock or jar, and releases it without any catching or jumping.”[5]

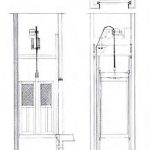

An even stronger suggestion of a commercial connection between McLauthlin and Sedgwick is found in McLauthlin’s catalog drawing of its standard invalid lift, which was a slightly modified version of Sedgewick’s original 1907 drawing. (Compare Figure 4 to Figure 1.) No overt connection between the two companies has been discovered, and, while it’s possible the Sedgwick image was repurposed by the publisher of McLauthlin’s catalog — serving as a stock image of an invalid lift — given that the majority of these types of drawings depicted specific machines, this seems unlikely.

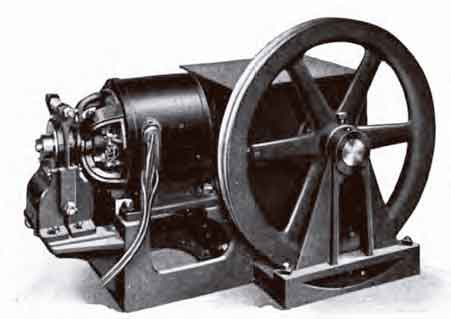

Energy Elevator Co. of Philadelphia also manufactured invalid lifts during this period. Its 1917 catalog included a description and illustration of its automatic hand invalid elevator (Figure 5). In the late 1920s, it also introduced an electric invalid elevator while continuing to build its standard hand-powered machine:

“We are now making an electric lift for residences and find it very much appreciated wherever used, especially by convalescents and invalids. The touch of a button starts this elevator, and it stops automatically at the top and bottom landings, where it is held by an electric brake. The construction is the same as the Hand Invalid Elevator and is, therefore, of the sturdiest build possible, and absolutely safe. It will carry a load of 500 pounds at 50 feet a minute. If the buyer can afford it, we advise taking the electric type in preference to the hand, as it is well worth the difference in cost.”[6]

This elevator was, in essence, a mini-traction machine (Figures 6 and 7). The electric motor was described as “2-3 phase, 220 volts, and 6.0 cycles,” and the elevator was furnished with a controller, door contacts, reverse- phase relay, limit switches and push buttons.

The history of the invalid lift from its origins in the 1860s to the introduction of the electric invalid lift in the 1920s traces one important aspect of the industry’s pursuit of the residential elevator market. While other “home elevators” were marketed during this period, the commercial focus on the elevator as an affordable solution to meeting the needs of persons with disabilities, rather than as a luxury item, drove the development of the hand-powered invalid lift.

It is of interest that all invalid lift manufacturers were regional companies — Otis is conspicuously absent from this story. While Otis did pursue the development of an electric residential elevator in the early 1900s, its intended market was not that pursued by its smaller rivals. This is clear in one of the images used to market these elevators, which depicted, as described in Otis’ catalog, a “typical entrance to an Otis residential elevator” (Figure 8).[7] This image represents a very different domestic world from that of the typical invalid lift user.

- Figure 1: Invalid lift, Sedgwick Machine Works (1907)

- Figure 2: Invalid lift, Sedgwick Machine Works (1914)

- Figure 3: Invalid lift, Sedgwick Machine Works (1920)

- Figure 4: Invalid lift, George T. McLauthlin Co. (c. 1915)

- Figure 5: Invalid lift, Energy Elevator (1917)

- Figure 6: Electric invalid Lift (plan and sections), Energy Elevator (1928)

- Figure 7: Electric invalid lift motor, Energy Elevator (1928)

- Figure 8: Otis electric residential elevator (c. 1900)

References

[1] Sweet’s Indexed Catalog of Building Construction for the Year 1907-08, New York: The Architectural Record Co. (1907).

[2] “Elevators for Invalids,” Sedgwick Machine Works advertisement, The National Builder (March 1912).

[3] “The Utility of the Dumb Waiter,” Hardware and House Furnishing Goods

(February 1919).

[4] “O’Neill Invalid Lift,” Hardware Dealer’s Magazine (November 1912).

[5] Geo. T. McLauthlin Co., Hand Elevators: Bulletin 113, Boston (c. 1915).

[6] Elevators Manufactured by Energy Elevator Co.: Catalog No. 29, Philadelphia (1928).

[7] Otis Elevator Co. Otis Residence Elevators (c. 1900).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.