The National Association of Elevator Contractors 1950-1974: Building Community

Apr 1, 2024

An association is born.

The founders of the National Association of Elevator Contractors (NAEC) faced a vertical-transportation (VT) industry dominated by the big two — Otis and Westinghouse — which controlled approximately 85% of the marketplace. A second tier of companies, which included the Montgomery Elevator Co. (Moline, Illinois), Armor Elevator Co. (New York City), ESCO Elevators, Inc. (Fort Worth, Texas), Southeastern Elevator Co. (Atlanta, Georgia), F.S. Payne Co. (Cambridge, Massachusetts), Rotary Lift Co. (Memphis, Tennessee) and U.S. Elevator Corp. (Los Angeles, California), controlled the majority of the remaining market. When asked in 1969 if the NAEC had been established as an “anti big two” organization, President Robert V. Jacobs responded:

“There may have been a few who felt that that should be the orientation of the association, or a part of it. If so, the history of the group would indicate that such a negative approach had short shrift and that the membership, and its committees busied themselves with attention to positive action. I don’t believe the steady growth could have been achieved by an ‘against’ attitude.”[1]

The positive, forward-looking attitude expressed by Jacobs was only a partial reflection of the founders’ intentions. What he doubtless knew, but failed to express, was that the NAEC’s creation was also predicated on the goal of establishing a cohesive VT community. This goal, however, was initially pursued within the context of a narrowly defined community group.

By the late 1940s, Montgomery Elevator Co. had established a nationwide network of approximately 40 branches and distributors, and the company hosted annual fall gatherings for their representatives and agents. In fall 1949, a small group met in Moline to discuss the possibility of establishing an organization that would ensure that contractors had “a better understanding of Montgomery’s problems” and that Montgomery had a better understanding of the contractors’ problems; this mutual understanding would establish a framework “in which they would help each other.”[2] This was followed by a second organizational meeting in February 1950 in St. Louis. In addition to members of Montgomery’s leadership, the second meeting was also attended by agents representing companies in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Illinois, Iowa, Missouri, Nebraska, Pennsylvania, Washington, D.C. and Wisconsin. The outcome of the meeting was the creation of the National Association of Elevator Contractors, with membership limited to Montgomery agents and representatives.

The founding members quickly realized that, while they constituted a distinct community of VT professionals, they did not represent the broader industry. The solution was to expand the definition of community. In 1952, they amended their Constitution to allow applications from members outside of the Montgomery “family.” An additional constitutional change, made that same year, further expanded the NAEC community through the creation of an Associate Member category, which allowed suppliers to join. By the end of the year, Rotary Lift Co. had joined (which also allowed their representatives to apply for membership). Other suppliers quickly followed, and by December 1952, the organization had 19 Active or Full Members and 8 Associate Members.

These changes fostered a steady growth in the NAEC community throughout the remainder of the decade: In 1954, there were 21 Active and 10 Associate Members; in 1955, there were 39 Active and 23 Associate Members; in 1956, there were 45 Active (which included the first Canadian member) and 35 Associate Members; and in 1958, the NAEC welcomed its 100th member. The expanded reach of the organization was also reflected in changes to the membership committee, which by the early 1960s had been reorganized into regional subcommittees. Each subcommittee was responsible for a specific zone: Zone 1: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Vermont, New Hampshire, Canada; Zone 2: Delaware, Washington, D.C., Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia; Zone 3: Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Florida, Tennessee; Zone 4: Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, Missouri; Zone 5: Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Wisconsin; Zone 6: Arkansas, Kansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas; and Zone 7: Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Nevada, Utah, Washington, Wyoming.

By 1962, the community had been further expanded by the creation of a third membership category: “Elevator inspectors, consultants, building planners, etc.,” were allowed to join as Subscription members. The 1960s also witnessed the removal of a final barrier to membership in the NAEC community. An important feature of this community was the fact that, while the members shared many common bonds, they were also competitors. This competitive spirit was evident among the association’s founders, and some had advocated a “one member per city” approach, which allowed a single company to be the sole representative from a given area. Although this attitude was gradually overcome and the community was expanded to allow multiple members from the same city, until 1964, a unanimous vote of the Board of Directors was required to approve a new member. A single “black ball” vote could defeat an application. In 1964, the Constitution was changed such that an application could be approved by the affirmative vote of 75% of the directors.

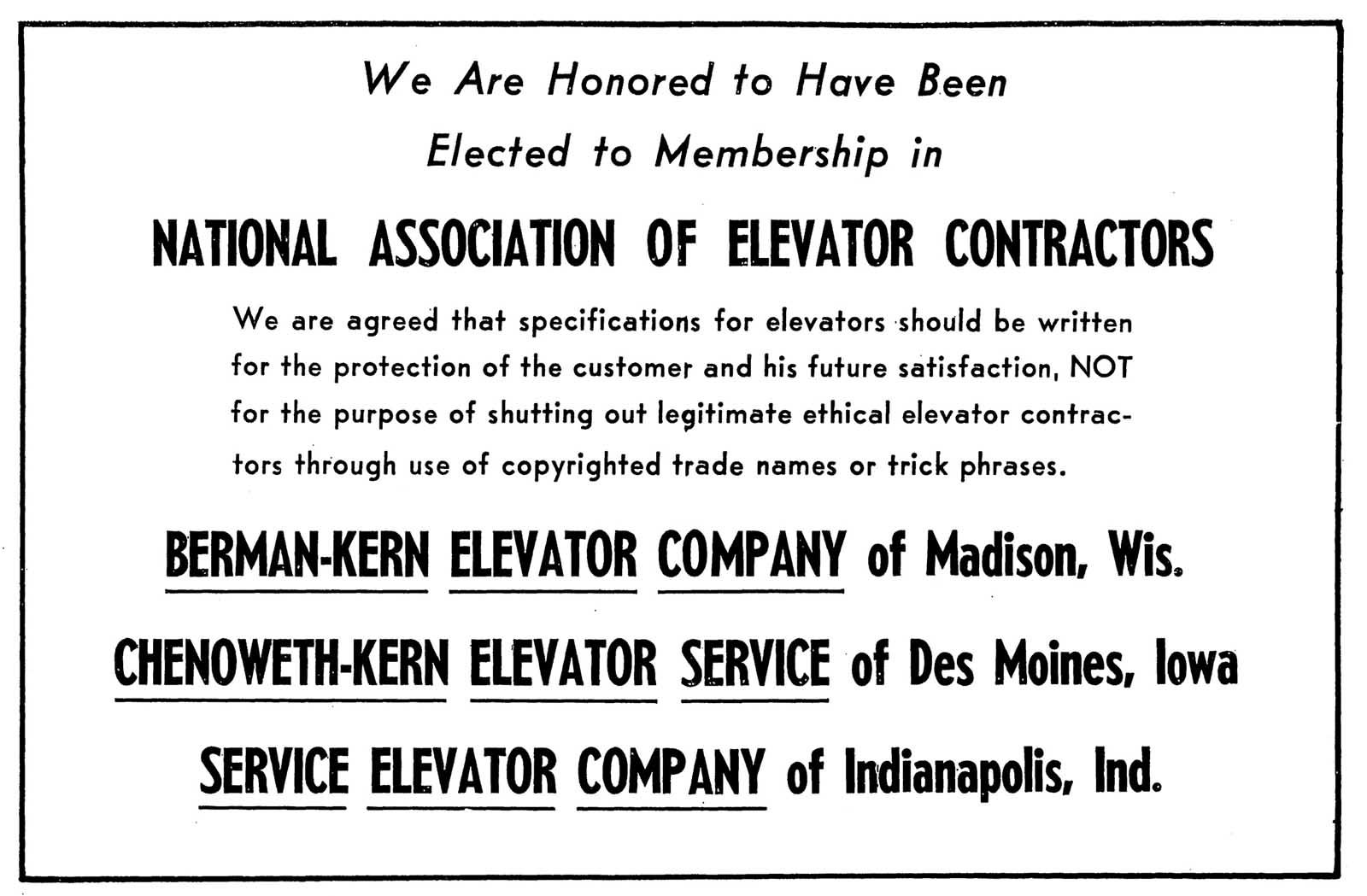

A robust membership is, of course, only one aspect of a thriving community. All successful communities have clearly defined governing documents. While these are often viewed as constituting the “rules” members must follow, when done properly, they also express the community’s values. The first public expression of the values espoused by the NAEC is found in an advertisement published in the February 1954 issue of ELEVATOR WORLD in which three companies announced they had recently become NAEC members (Figure 1). The companies jointly proclaimed that they “agreed that specifications for elevators should be written for the protection of the customer and his future satisfaction, NOT for the purpose of shutting out legitimate ethical elevator contractors through use of copyrighted trade names or trick phrases.”[3]

Seven years later, an NAEC committee elaborated on these values with the development of the organization’s first Code of Ethical Practices. The code, approved in 1961, stated:

“Be it resolved that we will conduct our business affairs in such manner that they will be fair to all parties concerned.

And further resolved that we will recommend only that which reflects good quality, safety, and best engineering practices for any given application.

And further resolved that we will respect our competitors deserving of our respect.

And further resolved that we will refrain from being derogatory.

And further resolved that we will not take unfair advantage of our suppliers.

And further resolved that we will always uphold the high standards of the purposes of NAEC.

And further resolved that we will refuse to be a party to any of the following price fixing, collusion, unfair labor practices, monopoly, non-code compliance, deviation from specifications after quoting or bidding, knowingly endorsing a member of this or any other trade association if they are not qualified or are known to be unethical or dishonest.”

The guiding principles expressed in 1961 concerning the ethical treatment of competitors, suppliers and clients, as well as core principles of fair business practices, were echoed in the revised, 1970 edition:

“The responsibilities and obligations of the elevator industry to the public, building owners, architects and its workers are many due to its position in the American business world. By furnishing quality construction, competent workmanship and the best in management, the people and country shall be served as expected. To fulfill this obligation, it is his duty to himself, to his customer and his industry to make a profit in his business. Ethical standards are essentially two-fold; that is, to establish principles of business conduct to be observed by the members in their relations: 1) with each other; and 2) with those who use their services. In either sense, they represent the minimum requirements for fair competition and honorable dealing within the concept of the Golden Rule. Accordingly, we recommend the following principles as industry policy and practice to all members of the NAEC:

1. Sanctity of Contract.

Contracts, whether written or oral, should be carried out in good faith to their full intent.

2. Employee Relations.

The welfare and success of employer and employee are independent and are of mutual concern, requiring respect, fair dealing and justice.

3. Contractor and Supplier Relations.

The dealings between contractor and supplier must be guided by the same principles of honor and fair dealing each party would desire if he were the other party. Proposals should not be invited or received for consideration from anyone who is known to be unqualified or from one who for some other reason has no genuine possibilities of being awarded a contract. In cases where [the] supplier is also contracting, he will so notify all contractors he is bidding the project when they have requested his supplier bid. The price of one competitor should not be made known to the other. In no case should [the] low bidder be led to believe that a lower bid has been received.

4. Architect Relations.

A contractors’ responsibilities to the architect are to keep him advised of the functions and responsibilities of the elevator trade and to advise him against uneconomical improper practices and limitations in specifications.

5. Competition.

Fair and bona-fide competition is not only desirable but necessary in American business. Any act or scheme to restrict fair competition is a breach of faith and a betrayal of principles. Any false or malicious word or act that would harm the reputation of a competitor is considered unethical and should be avoided.

The addition of the sections on employee and architect relations spoke to the growing awareness of workplace equity and the increasing importance of contractors also serving, when needed, as elevator consultants.

The strength of any community is, of course, most evident in the character of its individual members. Likewise, successful communities often owe their start to a single individual who provided the spark that lit the flame. In this case, that person was James W. (Jimmie) Bryce (1898-1956) (Figure 2). Bryce was born in Jacksonville, Florida, and he attended the University of Florida prior to transferring to Georgia Tech in fall 1919. Following his graduation in 1921 (with a B.S. in electrical engineering), he joined Otis. By 1924, he was managing their Miami office, and his subsequent career included 11 years in Otis’ New York office, three years in Atlanta as a sales-engineer and two final years in New York where he worked as an assistant to Otis’ general sales engineer. In 1944, he returned to Jacksonville where he launched the Bryce Elevator Co. Not long after he founded his company, he joined the Montgomery “family.” Bryce organized and led the 1949 and 1950 meetings that fostered the NAEC’s creation, and he served as its first president. He was described as “talented, energetic and unselfish in his relationship with others,” and his leadership was a pivotal aspect of the NAEC’s successful launch.[4]

The Montgomery agents who attended both of the NAEC’s organizational meetings included numerous individuals who played key roles in the association’s early years. This group included Clayton H. Shrout (1914-1994), who represented the Wright & Mack Elevator Co. of Omaha, Nebraska. Wright & Mack was founded in the early 1900s by George R. Wright (1849-1920). In 1914, the Shrout family moved from Kansas City to Omaha, where Charles Shrout (Clayton’s father), established an “elevator construction company.”[5] Nothing is known about this venture; however, during this period, Charles Shrout was an active member of the International Union of Elevator Constructors (IUEC), serving as president of Local No. 28 for several years. By the 1920s, he was employed by Wright & Mack as a manager, and by the early 1930s, he was identified as the company’s “proprietor.” In 1950, Charles, his wife Anna and Clayton incorporated the company.

Clayton Shrout’s primary role in the company was as its legal counsel (Figure 3). He received his law degree from Creighton University in 1939, and he maintained a practice in Omaha for more than 50 years. Shrout also played critical roles in helping to draft the NAEC’s constitution and bylaws and served as the association’s primary legal counsel for almost 20 years. In this role, he chaired the Legislative Committee throughout the 1950s and early 1960s. He also was a member of the first slate of officers, serving as secretary in 1950-1951. In 1972, he was elected an honorary NAEC member. Shrout’s presence at the association’s inaugural meetings was likely due to his parents’ support of the effort, which lead to Wright & Mack becoming a charter member. In 1953, following the death of her husband, Anna Shrout (1892-1976) assumed control of the company. She thus became one of the first women to lead an elevator company in the U.S. She was also the first woman elected to the NAEC board, serving as a director from 1965-1967 (Figure 4).

Ralph D. (Mac) McCaslin (1889-1967) was another NAEC founder who played several important roles during the association’s first decade (Figure 5). McCaslin began his VT career in 1914 with the Haughton Elevator Company (Toledo, Ohio). He held “various sales and management positions in their St. Louis office” for 22 years, leaving the company in 1936 to found the General Elevator Engineering Co.[6] McCaslin served as vice president (1951-52) and as the association’s third president (1952-53). In 1955, he retired from General Elevator.

This action did not, however, signal the end of his NAEC career. In 1956, he was hired as the association’s first paid executive director. This action coincided with the decision to move the headquarters to St. Louis and to hire an executive secretary to assist in running the office. McCaslin’s administrative partner was Minnette Forthmann, who had served as a member of the Executive Committee of the Jefferson National Expansion Association. In this role, she had “become interested in the elevators which General Elevator was installing in the famous Gateway Arch,” and had presumably become acquainted with McCaslin.[2]

In mid-1959, due to ill health, McCaslin resigned as executive director, and Forthmann stepped into that role, serving until 1968 when she resigned to take a position with a historic preservation society in St. Louis (Figure 6).

The 12 Montgomery agents who attended the 1949 meeting included three representatives from one firm — the Hunter-Hayes Elevator Co. of Dallas, Texas — which represented both a multigenerational elevator company (in terms of its leadership) and a multigenerational commitment to NAEC. Hunter-Hayes was founded in 1920 by J. Peyton Hunter Sr. (1864-1927) and George W. Hayes Sr. (1880-1934). Two of Hunter’s sons, Howard M. Hunter and J. Peyton Hunter Jr., joined the company in the early 1920s.

Following the deaths of the company’s founders, J. Peyton Hunter Jr. assumed the roles of president and general manager (Figure 7). In 1946, his son, Graeme Hunter (1923-2019), joined the company (Figure 8). Following his graduation from high school in 1941, Graeme briefly attended the University of Texas. After his service as a Marine pilot in the Pacific theatre during World War II, he pursued a business degree at Southern Methodist University.

Hunter-Hayes’ attendees at the 1949 organizational meeting included Graeme and Howard Hunter and George W. Hayes Jr., while J. Peyton Hunter Jr. attended the February 1950 meeting in St. Louis. Hunter Jr. later served as an NAEC director (1952-53 and 1954-55) and vice president (1953-54). Graeme served as a director (1957-58), secretary (1958-59) and, in 1959 — at age 35 — he was elected to serve as the NAEC’s 10th president. By this time, he was a vice president in charge of sales and estimating and was recognized for his leadership abilities. The announcement of his election in EW noted that the Dallas Times Herald had recently selected him as “one of the young men whose present leadership in Dallas marks him as a Leader of Tomorrow.”[7]

Although Joseph C. (Joe) Tamsitt (1901-1984), a member of the “older generation” of NAEC members, had not been present at the association’s founding meetings, his presence in the community was evident throughout the period from 1950 to 1974. While some of the precise details of Tamitt’s career have been lost, the evidence that remains reveals a remarkable individual. He earned an engineering degree from Southern Methodist University during the 1920s and, by the end of the decade, was employed by the Richards-Wilcox Manufacturing Co. (Aurora, Illinois). While at Richards-Wilcox, he received five patents: Relay (1933), Door Operator (1935), Electrical Contactor (1936), Elevator Signal Apparatus (1936) and Elevator Gate (1937). During the 1940s, he moved to Baltimore, Maryland, where he was employed as the chief engineer of the General Elevator Co. He then left General for Keystone Electric Co. in Baltimore, where he also served as the chief engineer. In 1967, he left Keystone for Horner Elevator Co. (Washington, D.C.), where he served as the director of Engineering, Production and Education. Although he retired from Horner in 1971, he remained an active participant in the VT industry and, by the mid-1970s, had established J.C. Tamsitt Elevator Consultants.

Tamsitt’s primary contribution to the NAEC community was his tireless commitment to industry-specific education initiatives. In February 1955, Tamsitt and Keystone Controls announced the launch of a free correspondence school for VT industry members. The program covered:

“(1) Diagram reading and analysis, (2). Explanation of components: motors, generators, rectifiers, resistors, reactors, timing relays, etc. and (3) Troubleshooting: Single-speed, A. C. through Hydraulics, and Variable-Voltage Control.”[8]

Tamsitt had, in fact, begun contributing articles to EW the year prior to launching the correspondence school. His articles were designed to illustrate and explain critical fundamental principles, and he continued this practice throughout the 1950s and into the early 1960s. The February 1957 issue featured the first publication of his best-known article, “Variable Voltage Made Easy,” which remains one the most popular technical articles written for the VT industry.

In 1960, the success of the correspondence school — and the associated workload for Tamsitt and his employers — prompted a shift in the program’s delivery. William C. Sturgeon, an NAEC founding member and founder of EW, agreed to “host” the initiative in his magazine (Figure 9). Beginning with the March 1960 issue, the magazine, on a regular basis, published lessons, diagrams and associated questions. Thus, “rather than Tamsitt having to correct examination papers,” it was “up to student/readers to plot their own courses and progress.”[2] In addition to the lessons written by Tamsitt, which were likely adapted from the earlier correspondence program, the new format was also designed to have a supplemental component composed of technical articles contributed by NAEC members. However, in 1966, Tamsitt reported that the NAEC portion of the program “had bogged down due to the inertia of members in submitting material.”[2] In fact, he reported that most of the supplemental material had been submitted by “outsiders.” In an effort to prompt greater participation, he drafted a list of article topics that was sent to the chief engineers of NAEC member companies. During this same period, the program was expanded and enhanced by the development of instructional audiotapes, and by 1967, approximately 30 companies had subscribed to the first series of 12 taped lessons.

Tamsitt’s administrative success in managing the NAEC educational program may have played a factor in the Board’s decision to ask him to serve as interim executive director in the fall of 1970. Tamsitt accepted the post and NAEC President Frederick Farnsworth expressed his:

“gratitude to Tamsitt’s employer, Horner Elevator Co., for the services of the former for which the latter would be reimbursed … Tamsitt was asked to function on loan from Horner Elevator until the first of the year while [the] screening committee studied the matter of securing a permanent executive director.”[2]

In 1971, the NAEC Board voted to hire Tamsitt as the association’s executive director. Following the announcement of this decision, President Walter H. Walker noted:

“Joe Tamsitt has been recognized by NAEC members for many years as one of the foremost technical consulting engineers on electrical apparatus. His initiative and dedication to elevator education has contributed significantly to many thousands in our industry and we now expect our association to move forward with new leadership and programs patterned to offer useful services to the elevator contractors and manufacturers comprising our membership.”[9]

Tamsitt served in this role until 1974 when he resigned at the conclusion of the NAEC’s 25th Annual Convention.

This brief examination of the creation of the NAEC community concludes with an individual who, like many of those discussed thus far, was with the association from the beginning. The attendees of the February 1950 meeting included William C. Sturgeon, president of the Mobile Elevator and Equipment Co. (Mobile, Alabama). Sturgeon served as NAEC vice president (1952-53) and president (1953-54). During his term as president, he launched EW, the first American publication devoted to the interests of the VT industry. Although the magazine’s initial success was dependent on NAEC members subscribing to and advertising in the magazine, Sturgeon maintained a respectful separation between the two enterprises. EW was not intended to be a NAEC publication. However, his dedication to the organization and its goals — particularly those focused on education and building community — meant that association-related content regularly appeared in the pages of the magazine.

During NAEC’s first 25 years, its educational focus was evident through the consistent publication of Tamsitt’s efforts and related articles. The growth and vibrancy of the NAEC community was equally evident in articles on its various leaders and, especially, in the photo-filled articles that documented the annual conventions. While Sturgeon recognized the importance of depicting the NAEC “at work,” he also recognized (and enjoyed) depicting the NAEC “at play,” as the members socialized together. After all, healthy communities understand how to work and play well together. The success of the efforts to build the NAEC community during its formative years laid the foundation for the next 25 years, a period that closed out the 20th century and positioned the association for the 21st.

References

[1] “The Industry’s Two Associations,” Elevator World (January 1970).

[2] William C. Sturgeon, Editor, “History of the National Association of Elevator Contractors 1950 – 1981,” Elevator World (1982).

[3] Advertisement announcing new NAEC members, Elevator World (February 1954).

[4] “James Witschen Bryce,” Elevator World (January 1957).

[5] “Charles N. Shrout Dies,” The Kansas City Star (January 6, 1953).

[6] “General Elevator President Retires,” Elevator World (December 1955).

[7] “Texan Elected President,” Elevator World (December 1959).

[8] “Correspondence School Announced by Keystone,” Elevator World (February 1955).

[9] “Round the Elevator World: Tamsitt to Operate NAEC Office,” Elevator World (p. 22).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.