The Passenger Lift’s First Decade (Part One)

Jul 6, 2022

The world becomes aware of the potential of VT during 1860-1869.

The period between 1860 and 1869 witnessed the gradual expansion of passenger lift use in Great Britain as architects, engineers, building owners and the general public became aware of the potential of vertical-transportation (VT) systems. This increasing awareness was actively fostered by articles published in engineering and architectural journals, and articles in newspapers. While the former served to educate the professional community, the latter introduced the public to this new technology. Following a similar pattern found in the U.S., articles published in London and other major cities were regularly re-published throughout Britain in small-town newspapers, which assured that reports on new lifts had a wide readership. Lastly, the initial pattern of British lift usage closely paralleled the early use of American elevators in that their primary application was in large urban hotels.

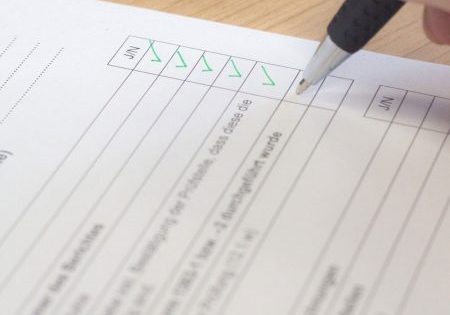

In 1857, planning efforts began on the Westminster Palace Hotel, proposed for a site in London on Victoria Street that overlooked the Houses of Parliament and Westminster Abbey. The design, by William and Andrew Moseley, was completed in early 1858 and a drawing of the main elevation and plans of the ground and first floors were published in the April 10th issue of The Builder.[1] While the drawings were accompanied by a brief article, which made no mention of lifts, the key provided for the plans did reference “lifts.” The plans indicated the proposed use of four lifts: two placed adjacent to the public stairs that served the upper floors, which were presumably intended for guests; and two that were apparently intended as service lifts (Figure 1). Although sitework began in June 1858, the project suffered a series of construction delays and the hotel was not completed until February 1861. Accounts of the building’s opening included references to a lift or hoist:

“Owing to the great height of the building, and the consequent tedious ascent that would have to be made to get upstairs, an ingenious contrivance in the shape of a hydraulic lift has been designed, by means of which, seated on a sofa with their luggage, visitors may ascend and descend from or to any of the six stories at pleasure.[2]

“The company have provided for the erection of a ‘hoist,’ a mechanical contrivance by which invalids and those who chose may be carried up to either floor at will, sitting on a chair or lying on sofa.”[3]

Interestingly, these accounts mention only one passenger lift. Additionally, a careful reading reveals the tentative nature of these statements, which, while they indicate that a lift “has been” designed and that the hotel owners “have provided” for the installation of a lift, they do not explicitly state that a passenger lift was actually present. In fact, when it opened, the building did not feature a passenger lift for the use of its guests. This deficit continued for over a year.

When the building’s architects gave a presentation on its design and construction to the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) in March of the following year, they reported that the “contract for completing” the passenger lift “still remains in abeyance.”[4] The reason for the delay is unknown. The architects did, however, provide a clear rationale for their decision to include a lift in the building:

“It was part of their original design that an ascending carriage should be supplied to the hotel, for reaching the upper floors; that it should be capable of carrying up persons day and night, at any moment, that this should be done with the greatest dispatch, free from danger, and that, as much as possible, noises in the working should be avoided … Taking all these circumstances into account, they determined upon one of Sir W. Armstrong’s hydraulic machines, as the contrivance most suitable for the purpose.”[4]

As was the case in the newspaper accounts, only one passenger lift was mentioned, which suggests that the design was modified after their initial publication. In addition to the broad specifications outlined above, the architects also discussed the importance of safety:

“The perfect safety of an apparatus of this kind became necessarily a matter of earnest consideration to the architects, as besides the constant superintendence of the conductor, who was to ride up and down with passengers, and by pulling the rope (acting on the valve) would stop the car at the floor intended to be reached, a further arrangement, to avoid personal risk from the breaking of the chain, was necessary.”[4]

The proposed “further arrangement” was a “safety check” designed by engineer James Carrick, whose firm had overseen the installation of “various smaller lifts for the hotel.”[4]

Carrick had accompanied the architects to the RIBA for their presentation, and he was invited to give a description of the proposed lift which, following William Armstrong’s patent, involved:

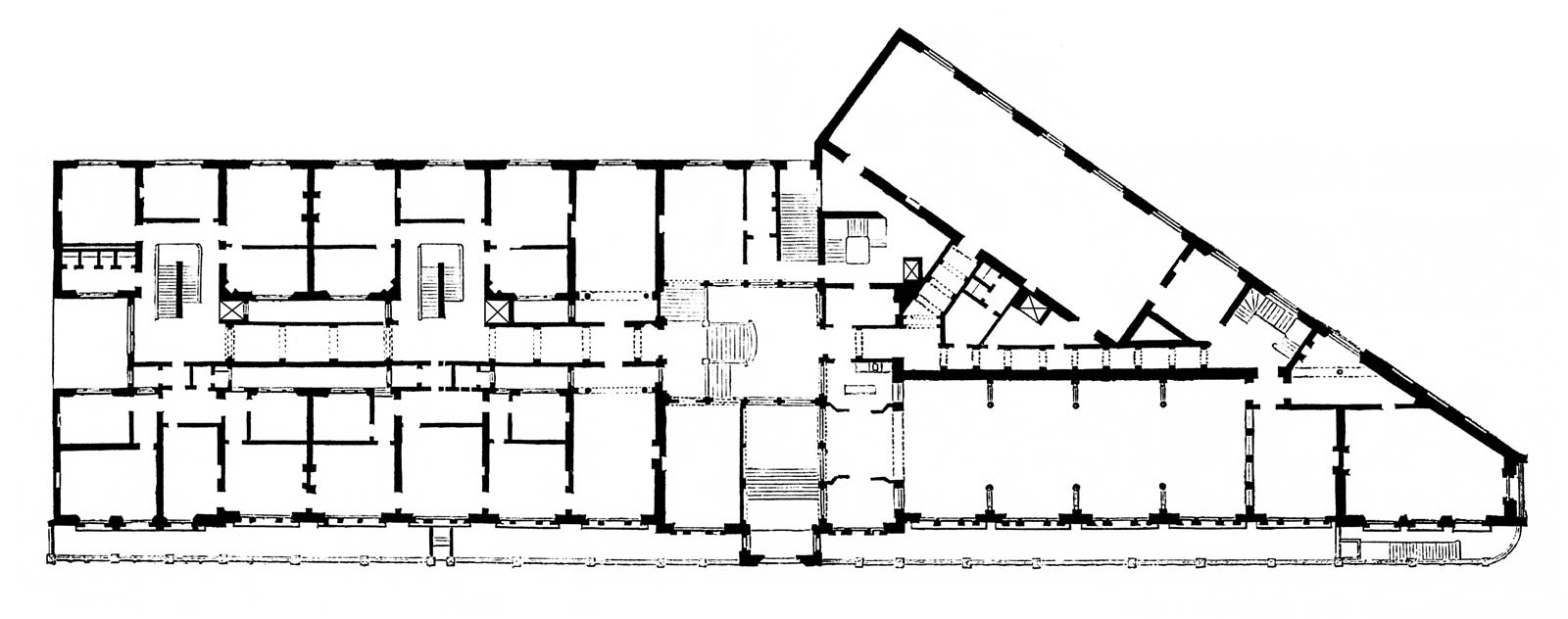

“[P]lacing of a hydraulic ram between sheave blocks. The car, being attached to one end of a chain reeved over these blocks, travels through a space equal to the stroke of the ram multiplied by the number of pulleys over which the chain is passed … The lift is designed to carry two persons and their luggage and the attendant, and is started and stopped at the respective floors by the attendant pulling the small chain shown in the drawing, which opens and shuts the valve of the apparatus. One hundred gallons of water is required for each ascent of the car. No water is required during its descent, the ram being so arranged as to descend by the counter balance of the car’s weight. Safety apparatus is provided, attached to the car: it consists of two teethed or ratcheted-faced eccentrics, placed on the end of the shaft or cross bar by which the car is suspended. The eccentrics are kept out of action by two powerful volute springs, but in the event of the main chain breaking they are immediately freed, and their force directed against the eccentrics, which bite the guide bars and so suspend the car.”[4]

Thus, the lift was proposed to utilize a horizontal roped (or “chained,” in this instance) hydraulic engine similar to that illustrated in Armstrong’s 1856 patent (Figure 2).[5] Unfortunately, although Carrick mentions a drawing, it was not published with the paper and has not been found. The lift’s limited size — a capacity of two passengers and the operator — in a hotel with over 200 rooms, reveals the designers’ uncertainty regarding how many people would actually use the lift. Carrick’s safety appears to resemble Elisha Otis’ 1854 design (which was patented in 1861), as well as a safety patented by British architect Hugh Baines in 1856.[6, 7] However, the description, while mentioning ratchets, does not reference pawls — the ratchets were intended to “bite” into the wooden guiderails.

Carrick’s presentation to the RIBA on the passenger lift proposed for the Westminster Palace Hotel is where this story ends. No mention of when a lift was placed in the hotel — or what type of lift was eventually installed — has been found. However, this presentation followed the completion of the Grosvenor Hotel, which was built near Victoria Station in London. Unlike its slightly older competitor, the Grosvenor featured a fully operational passenger lift when it opened in February 1862:

“A powerful hydraulic lift, by Messrs. Easton and Amos, for visitors, reaches from the bottom to the top of the building so as to accommodate every floor.[8]

“There is one staircase for servants in the northern end of the building, the corresponding space in the southern wing being occupied by a lift, the cage of which is eight feet square. This worked by a very simple hydraulic apparatus of Messrs. Easton and Amos, and passes up a shaft along the various floors of the building from top to bottom. It is equal to raising ten people at one time, though to render it perfectly complete the directors of the company ought to adopt such precautions as would prevent the cage coming down … in case of any failure [of] the hydraulic apparatus. It would also have been better if another smaller lift had been made, distinct from that intended for visitors, for taking down the dust and ashes.”[9]

The reference to the lack of a safety device is of interest, as is the perception that a service lift was needed to complement the passenger lift — and to segregate guests from hotel staff.

A detailed description of the Grosvenor Hotel lift has survived due to the fact that the hotel was the site of one of the first fatal passenger lift accidents, which occurred on June 12, 1865. On that date, the lift, containing the operator, three female guests, a hotel valet and a hotel porter, left the first floor intending to travel to the fourth floor. As the top of the car reached the fourth floor the occupants felt “a very heavy shock,” which was followed by the car’s uncontrolled descent to the bottom of the shaft.[10] The fall of the car caused the counterweights to “run with great velocity” toward the top of the shaft, where they apparently crashed into the overhead cast iron beams; the impact was such that the beams broke, and pieces of the broken beams and the counterweights fell onto and through the car.[11] This latter event resulted in one immediate fatality and injuries that resulted in the death of a second male passenger several days later. At the inquest, the hotel’s management stated that an engineer employed by the hotel “regularly inspects the lift, and oils it nearly every night.”[10] On the day of the accident (which occurred at 9:45 p.m.), the engineer testified that he had inspected the lift before leaving work and that “as far as he could see, it was quite safe, and in good working order.”[10]

An independent engineer charged by the coroner to inspect the accident site provided the following description of Easton and Amos’ lift:

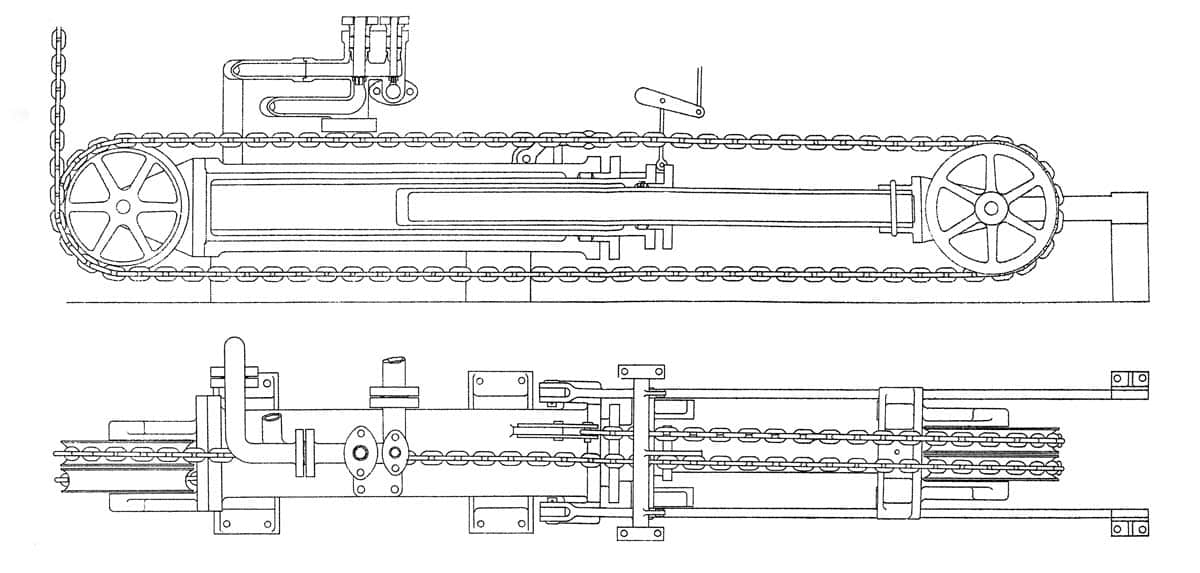

“The motive power … is supplied by a hydraulic ram, placed in a horizontal position under the basement floor, by means of which motion is given to a series of cog wheels, on to the shaft … of which are secured two iron drums two feet in diameter, round which are wound two iron wire ropes, passing thence over pulleys in the top of the building and attached to a strong ring in the top of the cage … To facilitate the ascent of the hoist and to assist in regulating it in its descent, and to take some of the strain off the wire ropes and the machinery generally, a heavy counter-balance weight is employed; this is attached to a long chain which, passing over pulleys fixed in a proper position in the top of the building, is attached to the top of the cage or hoist.”[11]

Unfortunately, the precise nature of the connection between the ram and the winding drums is unknown. It is possible that the machine used a rack-and-pinion connection similar to systems designed and patented in the early 1870s (Figure 3).[12]

The accident’s cause was attributed to the breaking of the winding drum shaft at the point where it connected with the driving cog wheels or gears. This failure “destroyed the connection between” the winding drums “and the resisting pressure of the water on the ram.” The car: “being thus left unsupported ran rapidly to the bottom; its fall, however, was partially retarded by the action of the counterbalance weight and chain and it is possible that there would have been no very serious results had it not been for the breaking of the girder at the top of the building and the consequent fall” of the beams and counterweight.[11] The inquest’s engineer reported that “an inspection of the broken part of the winding shaft shows that it had been partially broken, probably for some time before the accident; and that it at last failed by being actually twisted in two.”[11] Additional information in the report included a description of the car and counterweight. The car consisted of:

“[A] small movable cage or room, about seven feet square, made with wrought iron frames, at the top bottom and sides, the whole being strengthened and kept in proper position by diagonal braces of the same material, lined with a thin casing of wood and fitted with a floor, seats, etc. for the convenience of persons making use of it.”[11]

The car weighed approximately 7 cwts (1 cwt = 112 lb) and the lift’s capacity was given as 10 cwts, which was equal to seven passengers, “including the ‘liftman’ specially appointed to attend to this duty, and some baggage.”[11] The counterweight weighed approximately 26 cwts.

The inquest concluded on June 20 with a verdict of “accidental death,” and no fault found on the part of the hotel management or Easton and Amos. The lift’s builder testified that the accident was “certainly quite unlooked for,” and the hotel management assured the coroner that “the best skill which could be obtained in the refitting of the lift would be employed, and that any other accident should be impossible.”[13] While the popular press coverage of this accident was relatively generous in its assessment of responsibility, the professional press was slightly less charitable:

“It seems that there was a counterbalancing weight, but no safety brakes, such not being used in London as a rule, though they are in use in Manchester and elsewhere. This is a serious omission, and one which should be supplied in all lifts at present working without brake power. In the Bristol Royal Infirmary is a similar lift to that at the Grosvenor Hotel, but the precaution is taken of having a safety brake. A mechanical contrivance is attached which, in the event of the rope or machinery breaking, renders the car stationary, without the fear of its falling.”[14]

The complaint about the absence of a safety echoed the earlier newspaper account, and the reference to the application of safeties elsewhere in England prompts questions about the creation of lift safety standards.

In 1863, one year after the opening of the Grosvenor Hotel, the London Evening Standard reported that hydraulic passenger lifts were viewed as “indispensable” in hotel buildings of “inordinate height.”[15] And, while the 1865 accident at the Grosvenor was widely publicized, it did nothing to dampen hotel builders — and the public’s — enthusiasm for this new transportation system. The conclusion of this article will explore lift use in England during the remainder of the 1860s.

References

[1] “Westminster Palace Hotel,” The Builder (April 10, 1858).

[2] “Westminster Palace Hotel,” Yorkshire Gazette (January 19, 1861).

[3] “Westminster Palace Hotel,” Oxford University and City Herald, (February 16, 1861).

[4] Andrew Moseley, “An Outline of the Plan and Construction of the Westminster Palace Hotel,” Papers Read at the Royal Institute of British Architects, Session 1861-1862, London: RIBA (1862).

[5] William G. Armstrong, Hydraulic Hoisting Machines, British Patent No. 967 (October 21, 1856).

[6] Lee E. Gray, “The Historical Importance of Elisha Otis’ 1854 Exhibition at the New York Crystal Palace,” Elevator World (February 2022).

[7] Hugh Baines, Improved Machinery or Apparatus to be Applied to Hoisting and Other Lifting Machines, British Patent No. 2655 (November 11, 1856).

[8] “Grosvenor Hotel, Pimlico Station,” The Borough of Marylebone Mercury (February 22, 1862).

[9] “London Hotels,” Hereford Journal (April 12, 1862).

[10] “The Accident at the Grosvenor Hotel,” London Evening Standard (June 15, 1865).

[11] Maria L. White, Westminster Inquests, Thesis: Yale University School of Medicine (1980).

[12] Albert Lucius, Improvement in Hydraulic Hoisting Apparatus, U.S. Patent No. 118,031 (August 15, 1871).

[13] “Summary of This Morning’s News,” Pall Mall Gazette (June 20, 1865).

[14] “Hydraulic Lifts,” The Building News (June 23, 1865).

[15] “Metropolitan Improvements: VIII – Hotels,” London Evening Standard (January 28, 1863).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.