Nineteenth-century design with unique history was employed in a wide range of buildings.

One of the most intriguing hydraulic elevator systems developed in the 19th century was the water-balance elevator. Its use in the Western Union Telegraph Building in New York City was explored in From the Ascending Room to the Express Elevator: A History of the Passenger Elevator in the 19th Century, published by Elevator World, Inc. in 2003. While its use in this important early skyscraper was one of its most publicized installations, recent investigations have revealed that the water-balance elevator was employed in a wide range of buildings during the 1870s and 1880s. These investigations also revealed that this system was the result of a sustained research effort and that it had an intriguing production and manufacturing history, which involved numerous companies in Boston and Chicago.

This story begins in Boston in the late 1860s, when Cyrus W. Baldwin joined other inventors in the quest to perfect the “safety elevator.” In March 1869, The Boston Post reported on the “exhibition” of “a perfect safety stop” at the Oxnard Sugar Refinery in Boston.[1] The safety had been “recently introduced by the Baldwin Safety Elevator Co.”[1] The design was based on Baldwin’s 1867 patent “Improvement in Elevators,” U.S. Patent No. 70,941 (November 19, 1867), which concerned an automatic safety that gripped the guide rails if the hoisting rope broke. The exhibition of the safety device involved repeatedly cutting the hoisting rope on a car loaded with four tons of material. Each time the safety was activated, the car stopped after a descent of only 2 in. The device was designed to be installed on existing elevators, and, by March 1869, nine Baldwin safeties were in use in Boston. The newspaper further stated that the safety also operated if the elevator exceeded a preset speed, which was not a feature addressed in Baldwin’s patent. The development of this improvement was highlighted in an advertisement published in October 1869, which read:

“We have also perfected, with great study, expense and labor, a governor, to prevent the running down of elevator carriages. The governor acts when the carriage runs at a higher rate of speed than intended, and causes the safety to act and stop the carriage at once.”[2]

Unfortunately, this publicity and the effort to improve the safety device did not translate into commercial success, and the new company lasted less than one year. However, Baldwin was not deterred by this failure, and, in 1870, he joined with Boston businessman Edgar W. Clark to found Baldwin & Clark. The new company offered a somewhat eclectic range of products: “boot and shoe machinery, Baldwin’s Safety Elevator for warehouses, and the Water Balance Elevator for hotels and private dwellings.”[3] This marked the first appearance of the term “water-balance elevator,” and the new system was predicated on a design embodied in Baldwin’s second elevator patent: “Elevator for Hoisting Human Beings, Merchandise, etc.,” U.S. Patent No. 99,049 (January 25, 1870).

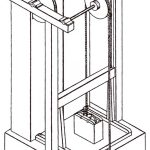

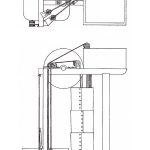

The essential components of the water-balance elevator were: a water supply tank at the top of the shaft, a water return tank in the cellar or basement, a large “bucket” connected to the car via ropes that passed over a sheave at the top of the shaft and a device in the car that allowed the operator to fill and empty the bucket (Figures 1 and 2). The initial water-balance scheme was not predicated on the system driving the elevator, but on producing a perfect equipoise between car and bucket that allowed the car to be easily raised and lowered. The elevator’s operation was described as follows:

“As soon as the attendant feels convincedthat the weight of the water within the bucketis sufficient to equalize the weight of the carriage, he releases his hold of the cord and allows the valve within the bucket to close, whenhe will at once ascertain whether the two areequal; if not, one or two trials, which need occupy but a few seconds of time, will renderthem so.”[4]

After equipoise had been achieved, the car could be raised or lowered “by means of the proper machinery or by manual power of the attendant.”[4] The patent drawings depicted a hand-powered system (an endless hand rope passing through the center of the car), and the water supply tank and bucket valves were controlled by shipper cables passing through the car (seen passing over the two small sheaves in Figure 2). Perhaps surprisingly, no braking device was discussed in the patent.

Baldwin continued working on improving his elevator throughout the year. He patented an improvement on his original safety device in November 1870, and, in January 1871, he received his second water-balance elevator patent: “Hydro-Atmospheric Elevator,” U.S. Patent No. 111,030 (January 17, 1871). Although the more exotic hydro-atmospheric never replaced the more descriptive water-balance, its use did reflect an operational aspect of the new system Baldwin could have only discovered after building one of his elevators. The bucket traveled in a closed well or standpipe that ran from the water return tank to the supply tank. Baldwin found that, because the bucket fit snugly into the standpipe, a vacuum was occasionally created beneath the bucket when it ascended, and this adversely impacted the elevator’s operation. Baldwin solved this problem by installing an “air pipe” in the bucket that was open to the air beneath and which was higher than the top of the bucket (to ensure it could not be submerged). He also placed a cock or valve at the top of the pipe that could be adjusted such that the “resistance” of the vacuum could “be varied with respect to the load.”[5] However, Baldwin made no reference in his patent as to how the operator would control the air-pipe valve.

Baldwin also realized his elevator could function without an external power source. The elevator’s revised operation was simple: the operator opened a valve in the supply tank to transfer water into the bucket. When the bucket was filled with sufficient water such that it weighed more than the car, the elevator would ascend; when he wanted to descend, the operator opened a valve in the bottom of the bucket, and, when the car weighed more than the bucket, the car descended.

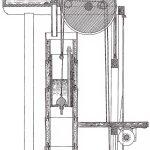

In addition to the air pipe, the January 1871 design also contained other improvements. It reflected a substantial refinement of the initial scheme (Figures 3 and 4). The improved standpipe design ensured the construction of a “stiff, watertight and durable object, at very small comparative cost.”[5] It employed an “inner cylinder of sheet metal. . . and an outer concentric jacket or casing of like material, the intervening annular space being filled with mortar, plaster or other suitable material or composition.”[5] To provide greater security while the car was stopped (and the counterpoise weight was adjusted by emptying or filling the bucket), Baldwin placed a large friction brake under the car. A wooden lever operated the brake, and it was also suggested that it could be used to control the car’s speed.

References to four Baldwin & Clark water-balance elevator installations have been found: three in Boston and one in Hartford, Connecticut. A newspaper account of the latter elevator, which was designed for use in the Charter Oak Life Insurance Co. Building, constitutes one of the earliest accounts of this system:

“The motive power is water, which is contained in a large tank in the upper story of the building and is let into a bucket, operating in an air cylinder, this bucket being packed with hemp and moving like a piston. The weights of the car and of the bucket, when empty, are alike. About 24 gal. of water are necessary to overcome the weight of one person, on the average. By means of a brake and a lever, the car is under complete control, and the speed can be regulated from 100 to 500 fpm. The car itself is finished with native woods, is handsomely carpeted and supplied with stuffed seats, and is altogether really an elegant affair, comparing favorably with the best in use in any of the first-class hotels in the country. In point of safety, the invention is a perfect success, as in every possible contingency, the automatic brake will hold the car and prevent accident to the inmates.”[6]

The reference to a potential running speed of 500 fpm highlighted what was to become one of this system’s primary selling points – its speed of operation. Unfortunately, the enthusiasm for Baldwin’s elevator expressed in the article, which appeared in May 1871, did not prompt sufficient commercial success, and Baldwin & Clark filed for bankruptcy on July 29, 1871.

The precise reasons for the business’ failure are unknown. Baldwin continued to work on improvements to his design, an effort reflected in his third (and final) water-balance patent: “Improvement in Elevators,” U.S. Patent No. 123,761 (February 20, 1872). Once again, he was undeterred by this failure and actively pursued a new means of manufacturing and marketing his elevator. In fact, the rights to his February 1872 patent had been assigned to Charles Whittier and Henry McBurney of Campbell, Whittier & Co. of Boston (soon to become Whittier Machine Co.). Although the details of Baldwin’s business relationship with Whittier are unknown, a November 1872 advertisement published in Scientific American reveals that the water-balance elevator had been added to the company’s manufacturing catalog.

The advertisement described Campbell, Whittier & Co. as “manufacturers of elevators of every description,” which included “Baldwin’s patented water-balance elevator for passengers and light freight, hydraulic elevators for private houses, wire-rope elevators of all sizes for stores and factories, Perkins’ patented double steel worm elevator for heavy freight and passengers, and Miller’s patent double-screw elevator for large platforms, and weighs 6-8 T.”[7] With the exception of Miller’s elevator, all of the machines were described as equipped with either “Merrick & Sons, Baldwin’s, or Thompson’s and Morgan’s patented safety apparatus.”[7] Thus, Baldwin appears to have given manufacturing rights to all of his patents to Whittier, Campell & Co. It is of interest to compare this lengthy description to the Otis Brothers & Co. advertisement found in the same issue of Scientific American. Otis simply stated that it manufactured “safety hoisting machinery.”[7]

The nature of Baldwin’s business relationship with Whittier is further clouded by the fact that, seven months prior to the appearance of the Scientific American advertisement, William E. Hale & Co. of Chicago had published an advertisement in the Chicago Tribune proclaiming it manufactured water-balance elevators and that prospective customers could see a “working model” in its newly completed building.[8] The conclusion of this article will follow the story of the water-balance elevator’s expansion into the western U.S., its continued use in the 1870s and 1880s, and its overall place in elevator history.

- Figure 1: Section drawing of water-balance elevator, Cyrus W. Baldwin, “Elevator for Hoisting Human Beings, Merchandise, Etc.” patent

- Figure 2: Axonometric drawing of water-balance elevator, Baldwin, “Elevator for Hoisting Human Beings, Merchandise, Etc.” patent

- Figure 3: Plan and section drawings of water-balance elevator, Baldwin, “Hydro-Atmospheric Elevator” patent

- Figure 4: Section drawing of water-balance elevator, Baldwin, “Hydro-Atmospheric Elevator” patent

References

[1] “A Valuable Protection to Life and Property,” The Boston Post, March 17, 1869.

[2] Baldwin Safety Elevator Co. advertisement, The Boston Post, October 5, 1869.

[3] Greenough’s Descriptive Gazetteer and Commercial Directory, Boston: W.A. Greenough, Jr. (1870).

[4] Cyrus W. Baldwin, “Elevator for Hoisting Human Beings, Merchandise, Etc.,” U.S. Patent No. 99,049 (January 25, 1870).

[5] Cyrus W. Baldwin, “Hydro-Atmospheric Elevator,” U.S. Patent No. 111,030 (January 17, 1871).

[6] “Safety Elevator,” Hartford Courant, May 8, 1871.

[7] Campbell, Whittier & Co. advertisement, Scientific American, November 23, 1872.

[8] “The Water Balance Elevator” advertisement, William E. Hale & Co., Chicago Tribune, March 7, 1872.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.