Tyler Elevator Doors, Circa 1919

Feb 1, 2012

A 1919 catalog from W.S. Tyler Co. and the technology and products offered during the period

In 1919, W.S. Tyler Co. of Cleveland issued Catalog No. 44: A Book of Elevator Enclosures and Cars. The catalog’s title, however, is somewhat misleading in that its primary focus is elevator doors and enclosures. In fact, this 129-page book permits a detailed examination of elevator door and enclosure systems in the first quarter of the 20th century. It also provides insights into contemporary marketing techniques and strategies. The catalog contains a two-part introduction followed by 14 sections that address aspects of elevator door operation and enclosure design.

The first half of the introduction is titled “The Purpose of This Book.” According to its author, the catalog was “issued to extend to the patrons of the company a distinct service covering elevator enclosures: giving detailed information as to arrangement, construction, design and finish.” The second half of the introduction, perhaps reinforcing the service aspect of the catalog, is titled “How to Use This Book.” This contains a brief explanation of the individual sections that comprise the remainder of the catalog, noting that “each section shows a variety of designs of the individual parts that make up the complete enclosure” and that a “complete enclosure can be selected to include any desired panel, transom, trim, pilaster, etc.”

Section One, “Assembled Designs,” features 17 drawings of elevator enclosures and includes 13 elevation and four perspective drawings, with two of the latter depicting elevators located in stairwells. The variety of elevator doors shown includes single, double and triple doors representing both sliding and center-opening door systems. Each image has an accompanying legend that provides detailed information, which is keyed to specific catalog pages and directs the reader to specific information on a given design, including the keyplate, panel, transom, glass, jamb, trim, frieze, sill, hardware and finish.

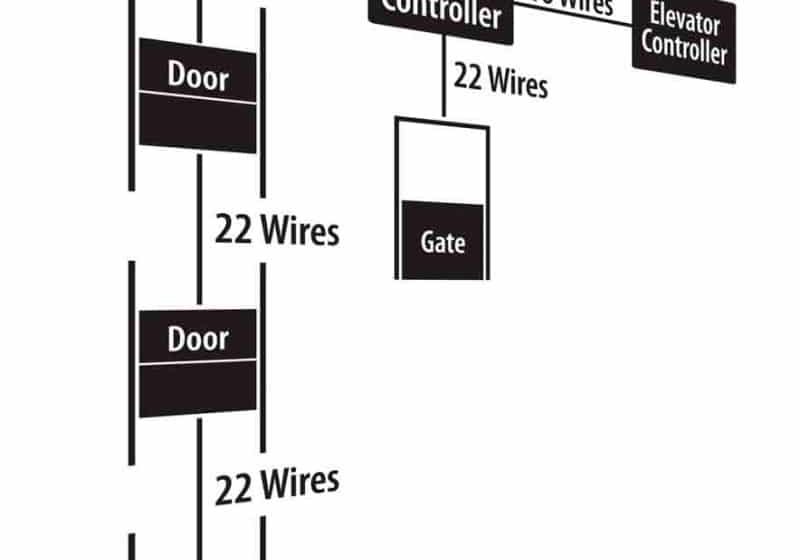

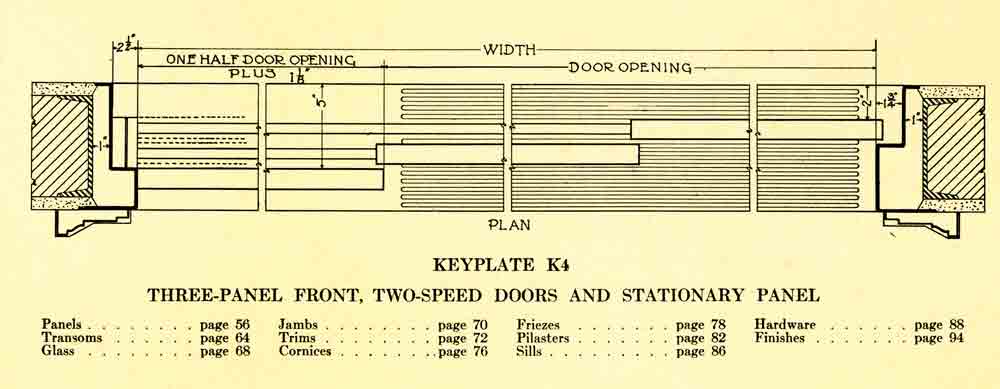

Section Two contains detailed plan and section drawings of 12 elevator enclosure types; thus, its title, “Keyplates,” is an appropriate designation. According to the catalog’s author, “The application of the keyplate to the hatchway condition is the initial step in selecting the design of the enclosure.” The plates illustrate the following elevator enclosure/door types:

- One-panel front, single-sliding door

- Two-panel front, two-speed door

- Two-panel front, single-sliding door and stationary panel

- Three-panel front, two-speed doors and stationary panel

- Three-panel front, single sliding door and two stationary panels

- Four-panel front, two-speed doors and two stationary panels

- Four-panel front, center opening doors and two stationary panels

- Five-panel front for two elevators, two pairs two-speed doors and one stationary panel

- Three-panel front, three-speed doors

- Center-opening, four-fold doors

- Swing door for push-button elevator

- Single sliding door for push-button elevator

The drawings are beautifully reproduced and offer a wealth of information about the installation and operation of the various door systems. Each includes critical dimensions and is predicated on 1.25-in.-thick elevator doors. It is interesting to note that two of the plates make specific reference to “push button” operation and that one of these, which depicts a typical “swing door,” reinforces the fact that the primary use of push-button elevators in the early 20th century was in apartment buildings and private homes.

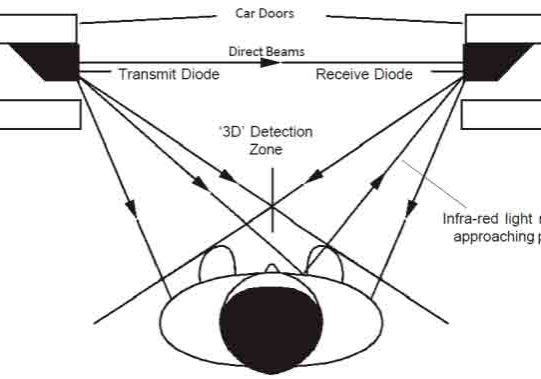

Section Three, “Panels,” contains illustrations of 42 door panel designs. The accompanying text notes, “7 ft. has been adopted for the standard height of door openings, but in special cases, this can vary.” Tyler door panels are described as “made of heavy-gage material, electrically welded into one piece, and reinforced to withstand the peculiar strains and stresses to which they are subjected.” Section Four addresses “transom panels,” characterized as having a dual purpose: allowing light into the elevator shaft and, in mercantile settings, allowing “customers to see the merchandise displays” while traveling through the building. This serves as a reminder of the “transparent” nature of elevator doors and enclosure systems in this period. Section Five addresses the glass used to provide this transparency. Tyler furnished six types of wire glass. The glass panels were set in “pure gum rubber” channels and were “held in place by continuous steel stops screwed to the panel frames and muntins.” Sections Six through Ten address various decorative features of enclosure design: jambs and soffits, trims, cornices, friezes and pilasters.

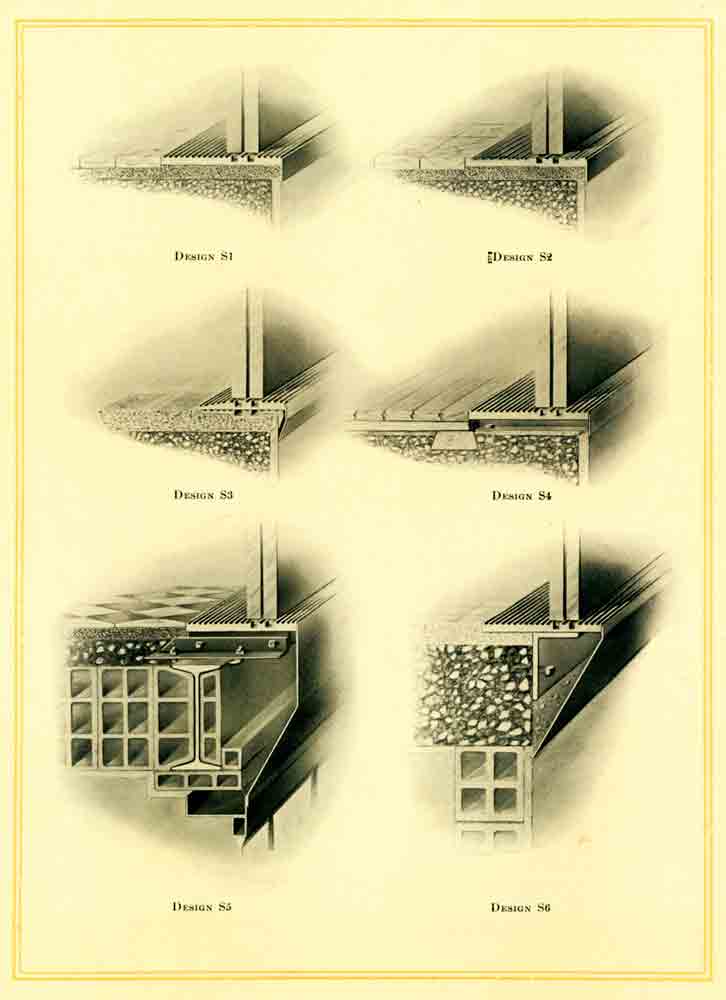

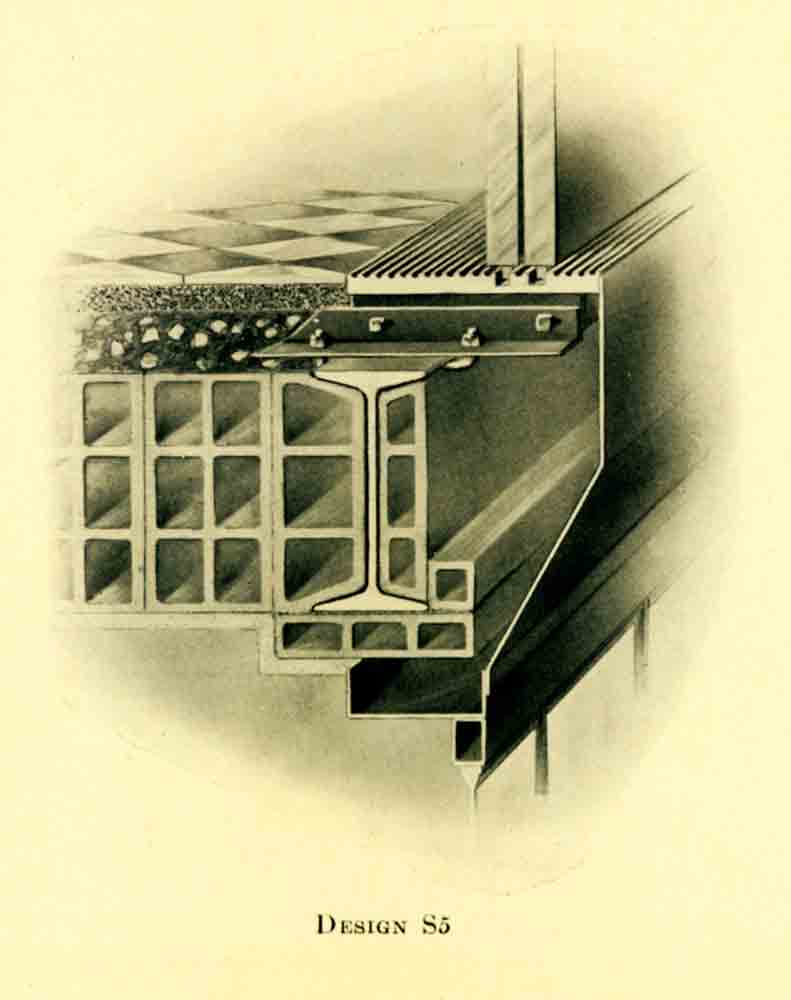

Section Eleven, “Sills and Fascias,” provides a level of detail similar to that found in the “Keyplate” section. However, instead of line drawings, this section employed rendered perspectival sections to illustrate the technical aspects of sill and fascia design and installation. The catalog states that the “sill is a very important part of an elevator enclosure front” and notes that “the noise and difficult operation of elevator doors can often be traced to faulty sill construction.” Tyler sills featured “safety surfacing” and were described as first “cast solid and extra heavy in sections without the grooves for the door guides.” The grooves were then “cut by machine to micrometer exactness, assuring absolute accuracy in alignment and a perfect fit for the guides, eliminating any possibility of noise or binding.”

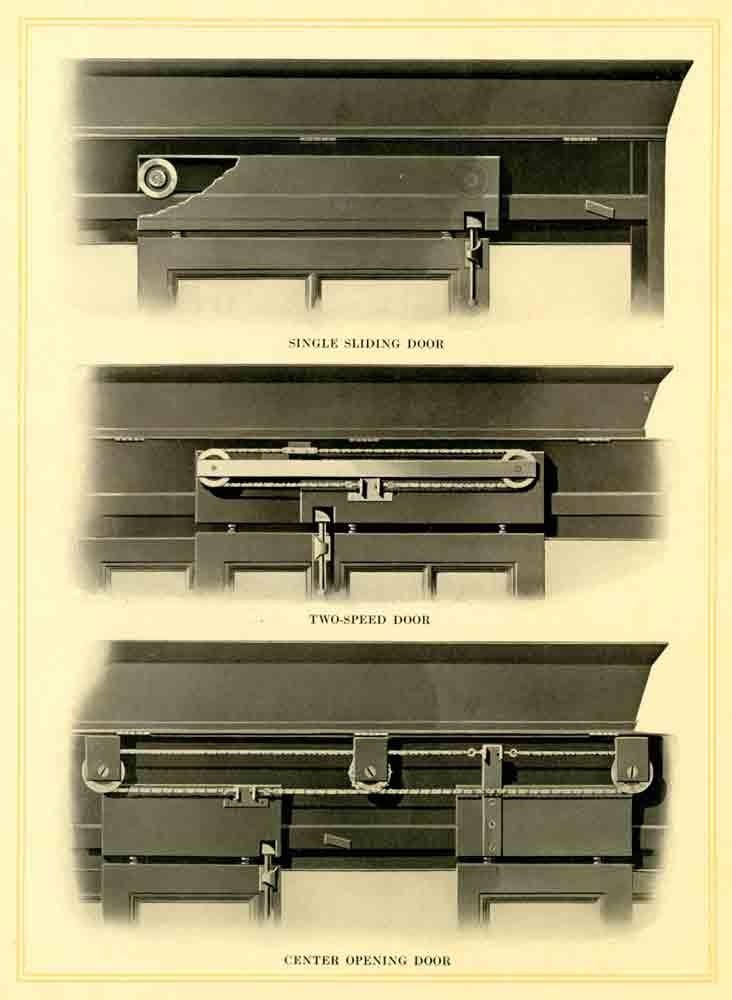

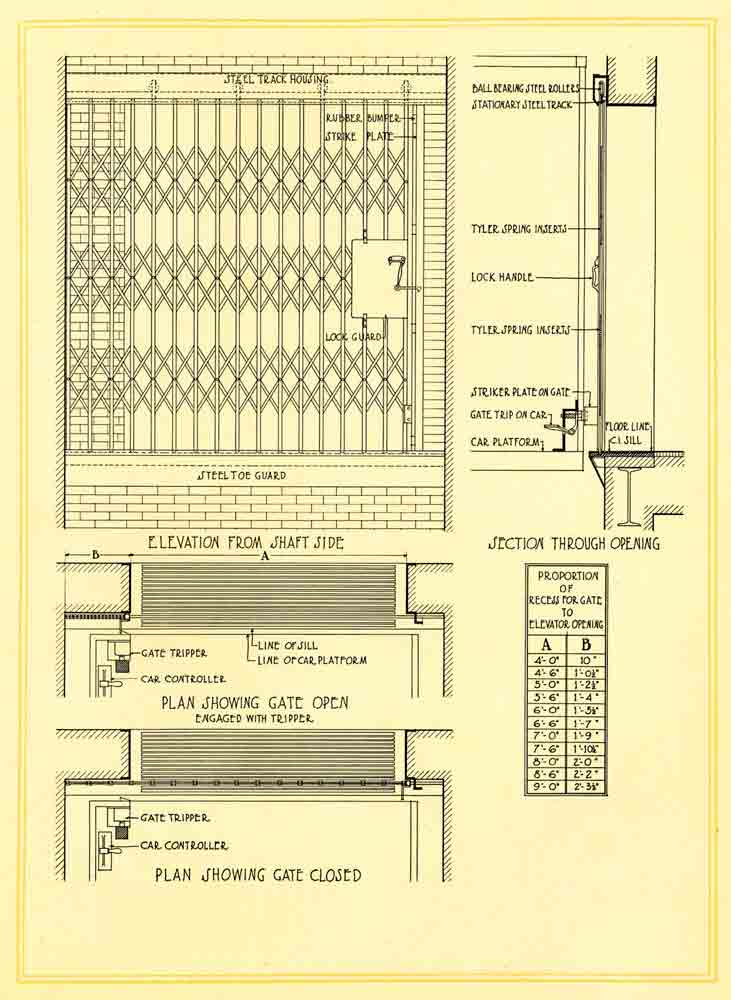

Section Twelve, “Hardware,” also relies on renderings rather than line drawings to depict the door hardware associated with single-sliding, two-speed and center-opening doors. All door systems utilized the “Tyler Ball Bearing Hanger and Silent Chain Device,” which operated in a “dust-proof housing” with “hinged cover plates” that gave “easy access for oiling and adjustment.” This section also provides information on and illustrations of two pull-down lock-bar systems, one pick-up lock-bar system, and a door closer and check device. Although not explicitly stated in the catalog, all doors appear to be hand operated, rather than motor driven. This is also true of the system described in Section Thirteen: the “Tyler Self-Closing Gate for Freight Elevators.” The catalog notes that this was a new “self-closing” design. The operator would pull the gate open by hand, then release it via a foot-operated “gate tripper.” Springs were built into the gate to ensure it closed automatically. The design also ensured that “closing pressure” decreased as the gate covered the opening.

The catalog concludes with Section Fourteen, “Finishes.” and Section Fifteen, “Elevator Cars.” The former illustrates – in beautifully reproduced images – 16 “grained enamel finishes” and 32 “solid color” enamel finishes. The final section contains 13 color renderings of elevator car sections that indicate the car profile, color scheme, decorative elements and proposed light fixture. The range of options shown in these final sections, coupled with the wealth of details found in previous sections, resulted in an effective marketing tool and useful resource for the catalog’s intended audience, “patrons of the company” who sought to specify a “complete” door and enclosure system for their building. In fact, at numerous points in the catalog, Tyler emphasized the need to specify a complete system built by a single manufacturer:

“To assure dependable and smoothly operating equipment, it is especially important to have undivided responsibility; therefore, all the parts required for the complete enclosure. . . should be included under one specification.”

Tyler’s marketing efforts included both the production of the catalog and a strategy to ensure its careful placement in the hands of its valued “patrons.” Each catalog featured a specially designed bookplate that could be placed inside the front cover. The bookplate came with the printed phrase “For the Business Library of. . .” followed by space for the client’s name and address. This information could be typed onto the plate prior to its placement in the catalog and delivery. The bookplate also included a space to record the individual catalog number, which was presumably intended to aid in tracking use and distribution. The catalog examined for this article (No. 457) was first given to the firm of Poor Thomas, architects in Portland, Maine, and was later passed on to Wadsworth, Boston & Tuttle Architects (also of Portland). The catalog had been furnished by Tyler’s branch office in Boston, a fact confirmed by the presence of a small decal inside the cover that provides the office address and telephone number.

Enclosure No. 2, A Book of Elevator Enclosures and Cars, Tyler (1919)

Keyplate No. 4, A Book of Elevator Enclosures and Cars, Tyler (1919)

Keyplate No. 4 (Detail), A Book of Elevator Enclosures and Cars, Tyler (1919)

Keyplate No.12, A Book of Elevator Enclosures and Cars, Tyler (1919)

Sill and Fascia Designs, A Book of Elevator Enclosures and Cars, Tyler (1919)

Sill and Fascia Designs (Detail), A Book of Elevator Enclosures and Cars, Tyler (1919)

Door Operating Hardware, A Book of Elevator Enclosures and Cars, Tyler (1919)

Self-Closing Gates for Freight Elevators, A Book of Elevator Enclosures and Cars, Tyler (1919)

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.