In this Readers Platform, Elevator Boutique’s Les Katz discusses the restrictions of the U.S. code for private-residence elevators.

Standards follow innovation but often to its detriment. Once applied, standards tend to inhibit creativity and new ideas, and are often anti-competitive.

Henry Ford didn’t have a driver’s license when he developed the Model T; the Wright brothers didn’t have their pilots’ licenses when they flew the first airplane. Otis sold elevators for about 50 years without a prescriptive design code. The licenses and standards’ restrictions came later, when a greater population would encounter the revolutionary marvels. We then regulated their operation and design with codes and standards with the purpose of trying to ensure safety of the vehicles and their passengers. The negative is that once codes and standards are established, nobody wants to accept responsibility for the negative outcomes and change them in a timely fashion, and it limits everything to do with the product.

Today, a still-emerging segment of the elevator industry, the private-residence elevator segment, is being stifled by a code that limits its ability to apply internationally accepted safety measures, architectural design elements, comfortable space and speed, and future innovations. The code for private-residence elevators – Section 5.3 of the ASME A17.1/CSA B44 code – has many problems. First and foremost, it is unsafe, as most famously exhibited by the recent case of Jacob Helvey (ELEVATOR WORLD, March 2014). There have been many other serious injuries and fatalities with design failures that comply with the code, which Otis first warned the industry about in 2003! It has been 12 years since that warning.

We at Elevator Boutique refuse to produce products by these code requirements that have failed; it would not be permitted in international codes as code writers are aware of the danger. The residential elevators designed by Elevator Boutique, based in Los Angeles, adhere to international standards, safer than those in the U.S. code, though not considered code compliant in all areas of this country. The knowledge of what happened in the one instance with Helvey should be enough to convince us of the major faults with the U.S. code, and yet, the code remains unchanged.

The term “code compliant” is interpreted by the greater population as “safe,” which, in this case, is untrue. It is up to individual companies to modify what they do. Some companies have already modified their products or are in the process of doing so (EW, April 2014), but other companies have decided to continue as before, modifying nothing. It costs money to change and is cheaper for companies to have their products adhering to the current code, for good or bad. Companies in the commercial elevator market, for the most part, long ago decided the residential business was not for them. They have largely stayed out of it, but it is those in the commercial business that have the determining vote when it comes to code changes in the residential segment. And, it appears they remain unmoved by the evidence that change is needed. It is illogical to have commercial elevator companies decide what residential elevator companies should design.

Codes for residential elevators are more performance oriented outside of the U.S., where there is a vibrant residential market. Elevator Boutique/ Lift Shop has had great success in Australia, Italy and China, where the codes are more progressive and safer. The U.S. code is considered farcical elsewhere, because it is absolutely prescriptive and is viewed as something to block competition, rather than promote safety. It is time for the language in the U.S. code to be performance based, not prescriptive based. The intent of the code is absolutely right, but its current methodology fails.

A second issue with the private residential code in the U.S. is its limitations on speed and size. Currently, residential elevators are allowed to travel 40 fpm, which is very slow. At 60 fpm, the passenger is equally safe, but it is a lot better for the passengers. According to the U.S. code, residential elevators are restricted in size to 15 sq. ft. and can only accommodate three people at maximum. This is too small for a wheelchair. My experience is that people are most comfortable with and want 17.2 sq. ft., which is the size internationally for wheelchairs.

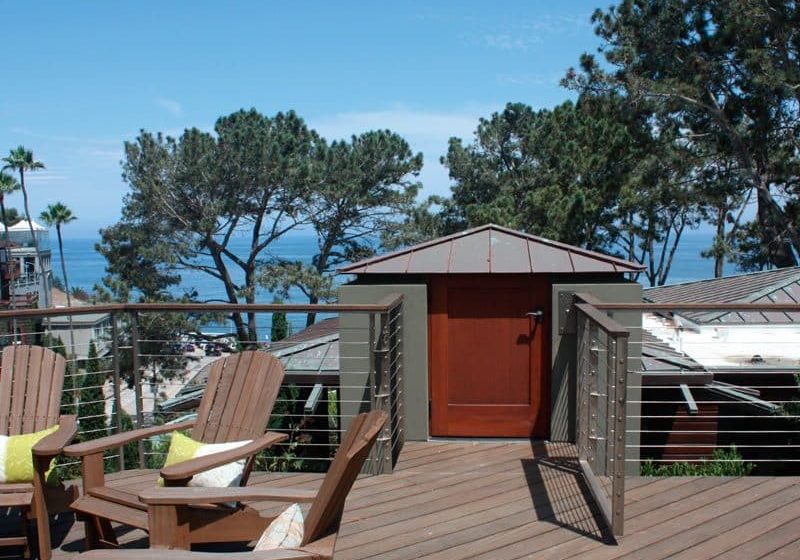

People take pride in their residential elevators; they are part of their home. It gives them convenience and the security that they have done the necessary future-proofing of their home, so they can relax in later years rather than plan to move out. They look at elevators as design features that can enhance the value and décor of the home and architectural possibilities. But, the U.S. sells residential elevators as a utility or an appliance, restricting their design and innovation options, rather than as potential attractive focal points. When we sell an architectural product, we collaborate with architects, designers and homeowners, and we put people to work – that is when we have the most fun and success.

The bottom line is, we serve a wide range of great clients, those of modest means and those of wealth, and we want to give each of them our best work with a quality product. Innovative products built well that are safe and attractive are our goal. This is an emerging segment in the marketplace, and we want it to grow and be good for everyone. The restrictive U.S. code makes this difficult. It is time for change, for the benefit of all.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.