A look into the life of an important industry innovator in the dawn of the electric age

William Baxter, Jr., author of Hydraulic Elevators, one of the first books on elevator technology (published by Engineer Publishing Co. in 1905), has a clear place in the history of vertical transportation (Figure 1). The book’s success attracted the attention of McGraw Hill, and they published a revised and substantially expanded edition in 1910 titled Hydraulic Elevators: Their Design, Construction, Operation, Care and Management. Baxter’s books are noteworthy for their detailed line drawings of elevator systems and components, and their thorough coverage of the topic. While his books focused on hydraulic systems, his work within the industry concerned electric elevators. In an 1896 article, Baxter described his involvement as follows:

“At the request of several of the officials of one of the large corporations in the elevator field, the writer took up the subject in the summer of 1884 and designed an electric elevator, as well as several arrangements for electrical control of the motion of the car. These officials were very enthusiastic upon the subject and anxious to start the manufacture of [the] electric apparatus at once, but the president did not believe that the time had come for such an innovation.”[1]

The “large corporation” Baxter referred to was Otis Brothers, and, in 1904, Thomas Brown (who began his career with Otis in June 1884 and was later employed as its chief engineer) corroborated Baxter’s account and added an important new detail:

“In 1884, Mr. William Baxter, Jr., had invented an electric elevator using constant current and had installed one in a building in Baltimore in 1887, yet it attracted but little attention and was not introduced further.”[2]

These brief accounts hint at the presence of a larger story. As will be seen in the following biography, there is much to tell.

William Baxter, Jr. was born in Troy, New York, in 1852. Shortly after his birth, the family moved to Newark, New Jersey. Very little is known about his early years; he received what was described as “an academic education”; however, it is unclear whether this included university studies.[3] He appears to have inherited his love of engineering from his father. William Baxter, Sr. (1822-1884) described himself as a “consulting engineer” and was a well-known designer of portable steam engines, including a successful model marketed as the Baxter Engine. At the start of his career, Baxter, Jr. (hereafter referred to as “Baxter”) initially appeared to follow in his father’s footsteps. His first patent, awarded in 1871, concerned an improved steam-powered pump, and his second patent (filed in 1874 under the names of both father and son) concerned a steam-powered canal boat.[4] In 1873, Baxter identified himself in the Newark City Directory as a “mechanical engineer.” (The basis for claiming this title is unclear, as no evidence has been found of him receiving any engineering education). That same year, he and his father established Baxter Steam Canal Boat Transportation Co. Although its founding was accompanied by enthusiastic and optimistic press coverage — the first boat built followed the design found in their 1874 patent — the company declared bankruptcy in August 1876. Its failure was primarily due to poor fiscal management.

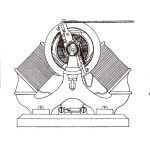

This business failure may account for the subject of Baxter’s third patent, which hinted at a very different future career path. Issued in 1877, it concerned a mechanical toy turtle (Figure 2). In his design, Baxter sought to “give a natural and life like action to the several or certain of the limbs of the animal by means which are both cheap and simple, and whereby the toy animal is made to move or propel itself in a natural and efficient manner.”[5] This, however, was his only patent for a children’s toy, and he quickly returned to his engineering practice.

While no detailed account of Baxter’s professional activities for 1877-1882 has been found, the limited evidence that exists suggests he gradually turned his attention to the pursuit of inventions related to the emerging new power source that had captured the country’s imagination: electricity. In April 1882, Baxter filed a patent application for an electric generator. The patent (awarded in February 1883) is revealing in that Baxter referenced numerous American and British patents in his text, which suggests he pursued a thorough investigation into this topic while developing his design.[6]

However, Baxter soon shifted his attention away from generators to electric light bulbs. He filed his first patent application on this subject in January 1883, followed by a second application in March.[7] Baxter was doubtless attempting to build on Thomas Edison’s work, the first phase of which occurred between 1878 and 1880. In November 1882, in anticipation of the commercial success of his designs (and prior to submitting his patent applications), he established Baxter Electric Light Co. The business was initially based in Jersey City, New Jersey, where he had moved in 1883. In 1884, he moved the company offices across the Hudson River to Manhattan, New York, where he rented offices in the recently completed Mills Building. Baxter’s work in this arena was later described as innovative in that he was credited as the first person to design an “enclosed arc lamp” with the arc placed within “an air tight globe.”[3 & 8] The Baxter Lamp attracted a modest amount of commercial interest; however, it was not enough to sustain the new company, and it ceased operation in 1886.

The timeline associated with the development of the arc lamp is important because it embraces the summer of 1884 — the period during which Baxter claimed that, at the request of Otis Brothers, he “took up the subject” of electric elevators.[1] The lack of evidence to support this claim, which was repeated by Thomas Brown in 1904, is intriguing. Baxter’s limited experience with electric motor design and the lack of any elevator-related patent applications from this period raise questions about his memory of these events. Additionally, no records of his alleged communications with Otis survive. What is known is that Baxter moved to Baltimore in mid-1886 to assist in the establishment of another new business venture: Baxter Electrical Manufacturing and Motor Co. Baxter was described as one of the company’s “incorporators” and its “electrician.”

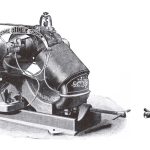

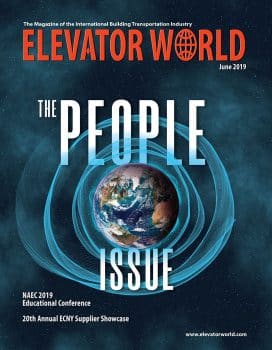

The focus of Baxter’s new enterprise was the invention and manufacture of electric motors designed for a variety of industry uses (Figures 3 and 4). His initial design efforts resulted in six patent applications filed between October 1886 and October 1887.[9] The patents (all of which were assigned to Baxter Electrical Manufacturing and Motor) concerned the design of an electric motor and an electric motor frame, governor, journal bearing, shunting device and automatic switch. None of these patents referenced elevators. This absence, however, did not mean that these motors were not employed in elevator systems. In October or November 1887, a Baxter motor was installed in Liebman Bros. & Owings’ Brooklyn department store to pump water into a “pressure tank” that served three hydraulic elevators. In January 1888, a second motor was installed in Brush Illuminating Co.’s Manhattan warehouse, where it served two hydraulic elevators, each with a capacity of 2500 lb.[10] In these applications, Baxter’s motor was simply taking over the role normally served by a steam engine.

In March 1888, a Baxter motor was once again used as a replacement for a steam engine; however, in this case, it played a more direct role in the elevator’s operation. The motor was used to power a “safety elevator” installed in William Lawton’s China Bazar in Wilmington, Delaware. The elevator was designed by John Taylor of Wilmington, who began building elevators in the early 1880s and advertised himself as a “manufacturer of. . . elevators, both steam and hand power, for manufactures, stores, stables, etc., furnished at short notice.”[11] Although direct-connected steam elevators were common in the 1880s, belt-driven machines were equally popular, particularly in industrial settings. Thus, it is very likely Baxter’s motor had a belted connection to the elevator mechanism. This was the pattern found in almost all early electric elevators. In this case, as with others, the advantages of electric power over steam were highlighted:

“The electric motor, which was installed by Baxter Electric Manufacturing and Motor Co. of Baltimore, in the China Bazar of William Lawton to furnish power for the passenger elevator, is giving great satisfaction. These motors are clean, noiseless and perfectly safe, as the young ladies in Mr. Lawton’s store find no difficulty in either starting or stopping all the machinery. The motor is situated in the basement, and the switch is located on the desk on the first floor, so that if the elevator is needed, the young lady at the desk simply turns the switch, and the power is on. There is an automatic switch provided with the Baxter motor which prevents any serious accident, such as a cable being broken, or gears being torn off, if the elevator gets away.”[12]

The description of the system’s operation appears to indicate that almost all aspects of Baxter’s motor design (as reflected in his patents) were present in this installation. The account also raises several questions. If it was possible for “the young lady at the desk” to turn on the elevator by simply flipping a switch, what happened next? It presumably had an operator, which prompts the question, “How was it controlled from the car?” Beginning in April 1888, Lawton’s advertisements included an announcement that all five floors of his store were “accessible by a John Taylor Safety Elevator.”[13] It is interesting that he did not include a reference to the elevator’s use of an electric motor, given that, in the article announcing its installation, “an invitation” was “extended to the public and especially to those interested in machinery, or who contemplate using power in any way, to drop in and see the motor and elevator in operation.”[12]

Once again, the timeline of Baxter’s work from 1886 to early 1888 does not appear to substantiate the claims made by Thomas Brown in 1904: no evidence has been found regarding an 1887 installation of a direct-connected electric elevator in Baltimore. Baxter’s work up to this point was, in fact, a prelude to his entry into the world of vertical transportation, which will be examined in part two of this biography.

- Figure 1: William Baxter, Jr.

- Figure 2: Mechanical toy turtle (drawings derived from “Improvement in Automatic Toys,” U.S. Patent No. 188,841 (March 27 1877))

- Figure 3: Baxter Electric Motor: (l-r) top, front and rear views (drawings derived from “Electric Motor,” U.S. Patent No. 361,115 (April 2, 1887))

- Figure 4: Motors manufactured by Baxter Electrical Manufacturing and Motor (1887)

References

[1] William Baxter, Jr. “The Electric Versus the Hydraulic Elevator,” Engineering Magazine, Vol. 11 ( June 1896).

[2] Thomas E. Brown. “Passenger Elevators,” Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers, Vol. 23 (1904).

[3] “Obituaries,” Machinery, Vol. 16 (February 1910).

[4] “Improvement in Steam Pumps,” U.S. Patent No. 113,725 (April 18, 1871) and “Improvement in Steam Canal Boats,” U.S. Patent No. 154,978 (September 15, 1874).

[5] “Improvement in Automatic Toys,” U.S. Patent No. 188,841 (March 27 1877).

[6] “Dynamo-Electric Machine,” U.S. Patent No. 271,972 (February 6, 1883).

[7] “Voltaic-Arc Light,” U.S. Patent No. 288,157 (November 6, 1883) and “Air-Tight Electric-Arc Lamp,” U.S. Patent No. 306,998

(October 21, 1884).

[8] “Obituary: William Baxter, Jr.,” Power, Vol. 32 ( January 25, 1910).

[9] “Electric Motor Frame,” U.S. Design No. 17,256 (April 12, 1887); “Electric Motor,” U.S. Patent No. 361,115 (April 2, 1887); “Horizontal Governor for Electric Motors,” U.S. Patent No. 361,116 (April 12, 1887); “Journal Bearing for Electric Motors,” U.S. Patent No. 361,117 (April 12, 1887); “Electrical Shunting Device,” U.S. Patent No.384,116 ( June 5, 1888); “Governor for Electric Motors,” U.S. Patent No.384,117 ( June 5, 1888); and “Automatic Switch for Electric Motors,” U.S. Patent No.449,660 (April 7, 1891).

[10] “The Baxter Motor,” The Electrical World, Vol. 11 ( January 21, 1888).

[11] Advertisement for John Taylor, The Wilmington Morning News

( January 11, 1886).

[12] “The Electric Motor,” The Wilmington News Journal (March 28, 1888).

[13] Advertisement for Lawton’s China Bazar, The Wilmington Daily Republican

(April 4, 1888).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.