Handrail placement is a key component in escalator safety.

Many thanks to everyone who responded to my last column about handrail sanitisation and training. It was interesting that there was a large response to my point about product-based engineers. I do absolutely accept that some people will only ever work on one product and, therefore, they will essentially follow a manual or flowchart to install that product, but I do reiterate my point that we also need well-rounded engineers who have a breadth of knowledge, as well as those with a depth of knowledge. I suppose it’s a bit like comparing Ian Botham, who was a good all-rounder (with a batting average of 33.5 in test matches and a bowling average of 28), with Shane Warne, who had an equally good bowling average but a lower batting average at 17.3! Both really superb cricketers in my opinion, but their skills were different (if you look at it based on statistics). “Do what you do do well,” as they say.

I want to touch on a standard that has caused me some concern for a while. I suppose I ought to clarify that statement in as much as the standard itself doesn’t concern me, but the fact that most building designers look at you with a blank expression when you mention it. It would be fair to say that most architects haven’t heard of the standard, yet I have sat through many a case where the architect has been criticised for not considering it.

The standard I am talking about is BS 5656-2(2004). Yes, it is 18 years old. It goes by the title of “ESCALATOR AND MOVING WALKS — SAFETY RULES FOR THE CONSTRUCTION AND INSTALLATION OF ESCALATORS AND MOVING WALKS. PART 2: CODE OF PRACTICE FOR THE SELECTION, INSTALLATION AND LOCATION OF NEW ESCALATORS AND MOVING WALKS.”

Within this standard, there is a really important clause, which, if you are working with architects and building designers, you need to make them aware of. It states:

7.3 Risks associated with location

The siting and type of escalator installed can introduce additional hazards. The trend by architects and developers to expose one or both sides of escalators over a void, and the changes made to the balustrade/handrail design on company escalators, can increase risks to users. Those responsible for the location of escalators should carry out risk assessments to identify what hazards are present, including foreseeable misuse, who is likely to be affected and which preventative measures need to be implemented to eliminate the hazard or reduce the risk to the lowest level.

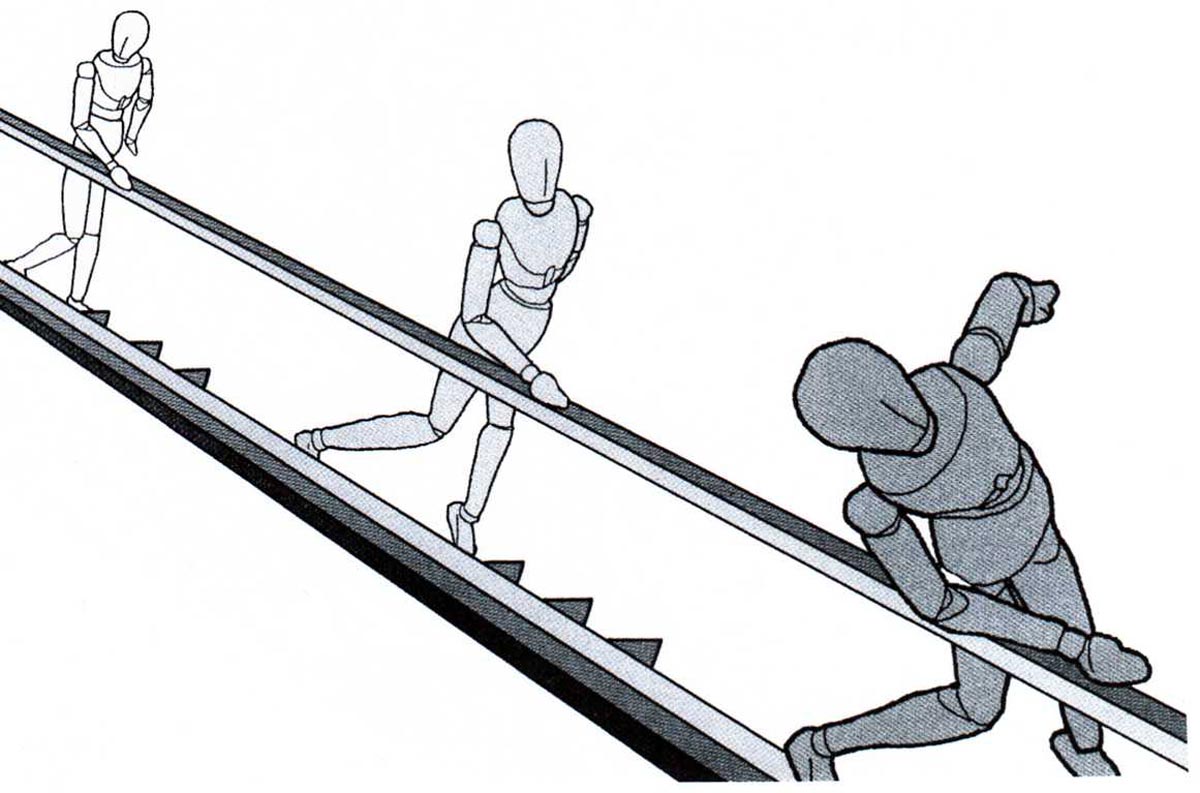

Examples of misuse include: sitting on, standing on, sliding down the handrail; holding onto the handrail from the outside of the balustrade at the lower landing; being lifted onto the handrail from the newel ends; walking up the outer decking; and sliding down the decking. All of these can result in serious injury.

Where escalators are not bounded totally by adjacent walls or partitions and are therefore exposed over a void on one or both sides, persons are at risk of falling a substantial distance. The building designer might need to make provision for some form of additional protection to be provided beyond the handrail and balustrade. This could, for example, take the form of a glass enclosure or glass shield at the exposed point or some form of guard rail.

There is also an increased risk of trapping between the moving handrail and the adjacent structure or escalator.

Periodic reviews of the risk assessments following the installation should be undertaken to determine the adequacy of the control measures.

NOTE: Attention is drawn to the Management of Health & Safety at Work Regulations 1999.

I know that many of you will say that I have been talking about this for many years, and that is true. My research into falls over or from the sides of escalators was published in 2011 after this standard was published, but people are still falling over the sides of escalators. If anyone would like a copy of my research, all you need to do is email me at [email protected].

Even before the standard was published in 2004, the industry knew about the problem of falls into voids. Indeed, ELEVATOR WORLD published an article by Dr. John Fruin on the matter as far back as 1993.

Another thing to bear in mind is the increased risk of falling over the side of a 35° escalator compared to a 30° type. There is an increased risk that when you fall forward on a down machine your hip might be above the handrail, especially on reduced height handrails (bearing in mind that the EN 115 standard allows a handrail to be between 900 mm and 1,100 mm.)

In summary, you have to think about where you put it and the foreseeable risks.

One of the falls over the side I found during my research was when a man had a child on his shoulders on the escalator and someone panicked and pushed a stop button. I don’t think that standard requires you to risk assess a passenger action as foolish as that but, clearly, there is a list of obvious risks that need to be considered.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.