A Houser Horizontal Hydraulic Elevator Engine, Part Two

Oct 1, 2013

Part one of this article series focused on a recently discovered Houser Elevator Co. horizontal hydraulic elevator engine brought to the attention of ELEVATOR WORLD by Gary Ritch of Syracuse, New York (EW, September 2013). This month’s article will explore the firm responsible for this remarkable elevator. The company’s story, from its creation in 1883 to the death of its founder in 1923, provides insight into the development of the elevator industry in Syracuse and — perhaps surprisingly — Minneapolis/St. Paul.

Unfortunately, very little is known about the company’s founder, Edgar W. Houser (1842-1923). Nothing is known about his education or professional training. He served in the U.S. Army throughout all four years of the Civil War. Following the war’s conclusion, he moved to Buffalo, New York, where he was employed by Howard Iron Works, one of the first firms to manufacture elevators in Buffalo. By the late 1870s, Howard built “hydraulic power and hand elevators for hotels, stores, manufacturers, etc.”; thus, Houser would have had a thorough education in the design of a variety of elevator systems. He moved to Syracuse in 1882 or 1883, where he found the local market dominated by a single individual: Hiram M. Graves, who first appeared in Boyd’s Syracuse Directory in 1880, where he referred to himself as an “elevator manufacturer.” The Memorial History of Syracuse, NY, from its Settlement to the Present Time (published in 1891) described Graves as the individual “who first manufactured hand elevators in Syracuse.” This work also stated, “In October 1883, E.W. Houser bought the stock, fixtures and machinery of H.M. Graves.”

These statements imply that Graves primarily manufactured hand-powered elevators, a supposition brought into question by his patent, “Elevator,” U.S. Patent No. 262,291, issued August 8, 1882, which concerned “power” elevators:

“The nature of this invention consists in a novel arrangement, with a power elevator, of a counterpoise operating directly on the drum or pulley, which transmits the elevating power to the car or platform, by which arrangement the weight of the car or platform can be overbalanced without affecting the tension of the elevating cable.”

Additional evidence exists concerning the extent of Graves’ manufacturing capabilities. However, the source of this evidence — the St. Paul Sunday Globe — shifts the story from New York to Minnesota. The March 30, 1884, edition of the newspaper announced Hiram Graves’ “arrival in St. Paul.” Graves proposed to establish “a prominent manufacturing industry that will at once be recognized as a matter of importance. . . in as much as it brings a branch not represented heretofore: that of building Improved Patent Safety elevators, both passenger and freight, in hand, steam and hydraulic power.” The paper also stated Graves came:

“. . . from Syracuse, where, and also at Buffalo, he has had a lifelong experience in this line of business. He has extensive interests in royalties on patents in both of these cities. . . [and] he brings with him an entire new equipment of machinery from the east, especially for the manufacture of elevators.”

Thus, Graves appears to have been one of the first to manufacture elevators in the Minneapolis/St. Paul area and to also have, perhaps, slightly inflated his résumé — he had earned only one patent prior to 1884, and no evidence exists that supports the claim of “extensive interests” in patent royalties from either Syracuse or Buffalo. The reference to his bringing “new equipment. . . from the east, especially for the manufacture of elevators” also brings into question the 1891 statement that Houser purchased “the stock, fixtures and machinery of H.M. Graves” and that this formed the basis for his new company.

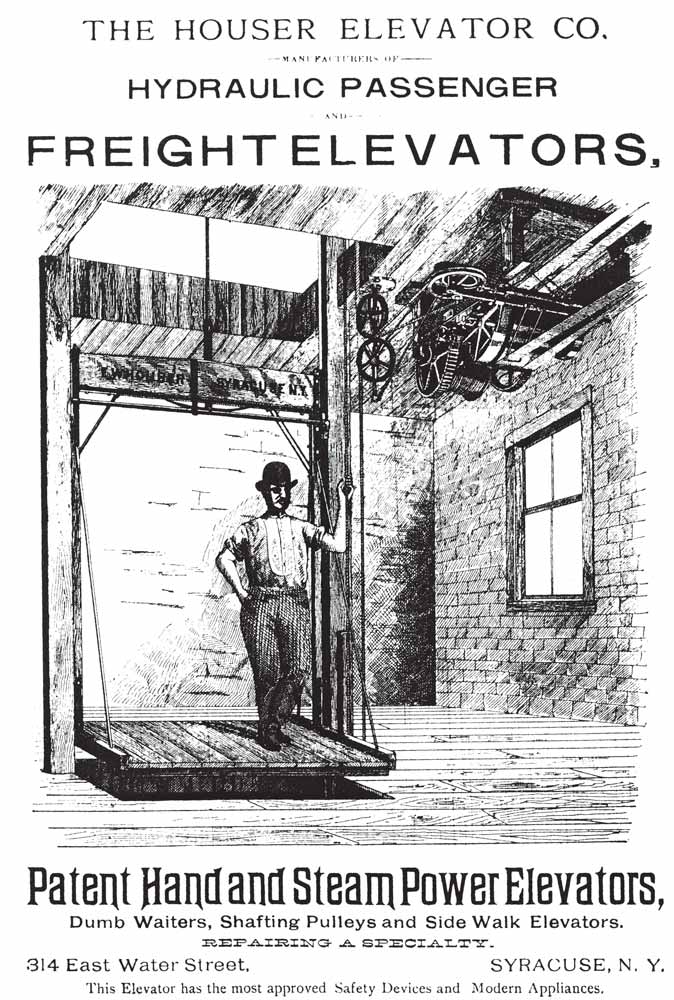

Nonetheless, whereas Graves had simply referred to himself as an “elevator manufacturer,” Houser established the E.W. Houser Elevator Manufactory. Advertisements published in the Syracuse Daily Journal reveal that by February 1886, he was able to offer customers a wide range of products that included hydraulic passenger and freight elevators, steam- and hand-powered freight elevators, sidewalk hoists, and dumbwaiters. Houser proposed that his “elevators and hoisting machinery” were suitable for use in “hotels, stores, manufactories, warehouses [and] dwellings.” He also carried a “full line of the best makes of wire rope,” as well as shafting and pulleys. Finally, he advertised that the “repairing of elevators” was a “specialty” and that such orders would be “promptly attended to.” By 1888, Houser had outgrown the quarters originally occupied by Graves at 77 Water Street and moved to a larger building further down the street at 314 Water Street.

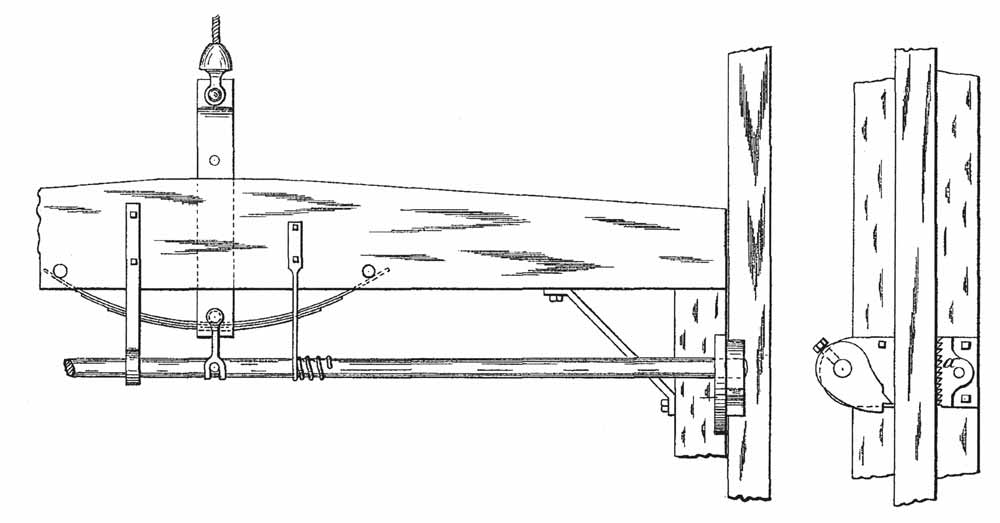

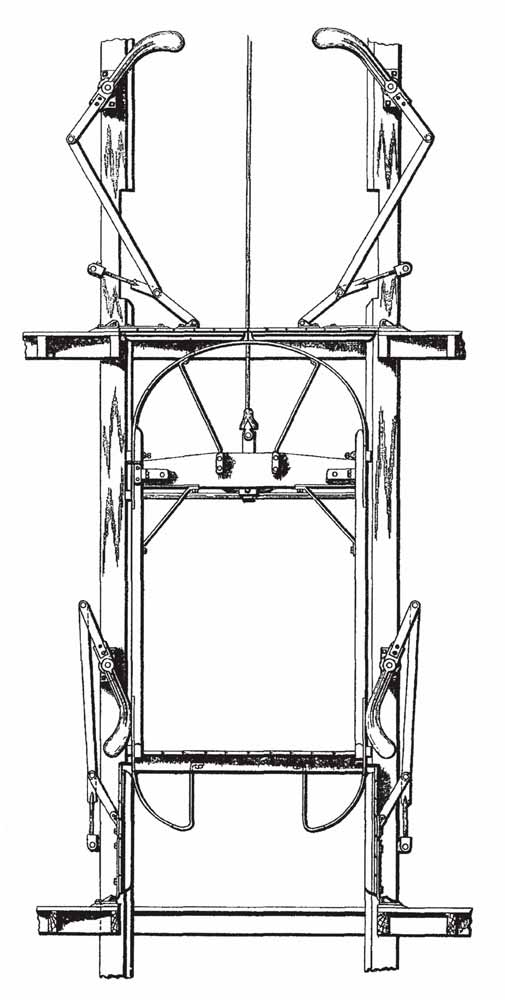

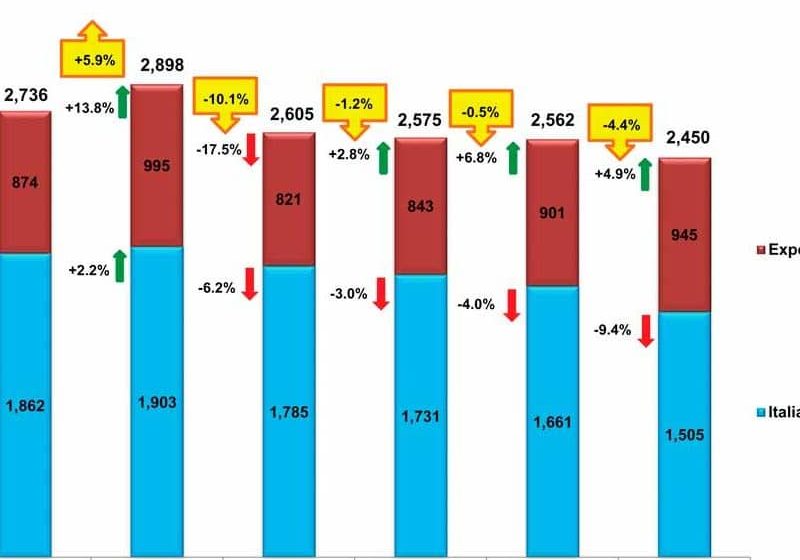

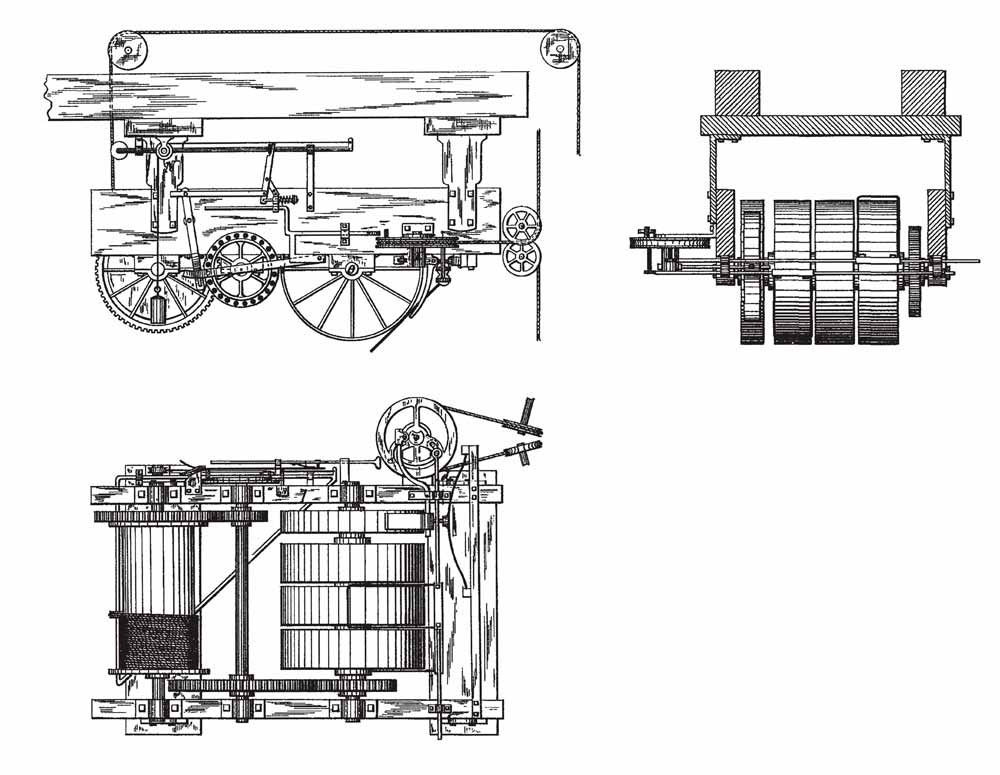

In May 1888, Houser also filed his first patent application, which concerned a spring-activated safety device: if the hoisting rope broke, a spring rotated a rod, which, in turn, pushed “jaws” into the wooden guide rails and stopped the car (Figure 1). The patent was “Safety-Clutch for Elevators,” U.S. Patent No. 405,555, issued June 18, 1889. Houser pursued two additional patents during this period: “Belt-Shifter for Elevators,” U.S. Patent No. 401,951, issued April 23, 1889, and “Elevator,” U.S. Patent No. 458,627, issued September 1, 1891. The first of these concerned improvements to belt-driven freight-elevator engines. The engine depicted in the patent appears to have been the model built by Houser; it also closely resembles the engine depicted in an 1891 illustrated advertisement (Figures 2 and 3). The second patent, titled “Elevator,” concerned a system whereby the car automatically opened and closed horizontal gates or hatchway covers as it traveled through the shaft. These gates, which were flush with the finished floor when closed, were a common safety device employed in factories and warehouses that featured open elevator shafts (Figure 4).

The company name on the 1891 advertisement — “Houser Elevator Co.” — marked the transition from the “E.W. Houser Elevator Manufactory” to a new business model that included a new partner: Clarence C. Decker (d. 1923). Unfortunately, almost nothing is known about Decker. In 1883, his occupation was listed in Boyd’s Syracuse Directory as “clerk,” and he appears to have contributed business skills to the partnership, while Houser had the mechanical skills. This assessment is, however, somewhat brought into question by the fact that the firm’s next two patents, which concerned improvements on Houser’s automatic hatchway cover design, were awarded to both Houser and Decker: “Elevator,” U.S. Patent No. 515,225, issued February 20, 1894, and “Elevator,” U.S. Patent No. 530,776, issued December 11, 1894.

In early 1902, the business was reorganized as a “stock company with increased capitalization.” Houser was named company president, while Decker served as secretary/treasurer. In 1910, company advertisements mentioned freight and passenger elevators; horizontal, vertical and plunger hydraulic elevators; steam-, electric- and hand-powered elevators; and patented automatic hatch doors. By 1915, it was building “full automatic push-button control elevators” and offered customers a “complete stock of elevator accessories.” The following year, it began to build traction machines. Houser retired around 1913, and Decker assumed the roles of president and general manager until his own retirement in 1922.

This brief history provides some of the context for understanding the elevator examined in part one of this series. However, questions remain concerning when it was built, who the client was, and when it was taken out of service. Fortunately, it is possible to trace the tenants and owners of 321 South Salina Street — the site of the Houser hydraulic elevator. The five-story building on the site was constructed in 1856. In the late 1880s, it housed S.C. Hayden & Co., a furniture company that also occupied the adjacent building, 323 South Salina Street. The two buildings apparently housed the firm’s showroom and factory. (In addition to selling furniture, the company built custom cabinets and upholstered.)

In September 1891, hat maker and seller F.J. West, Millinery purchased 321 South Salina Street, and its subsequent newspaper advertisements encouraged customers to “look through our entire building, which can be done by taking the elevator from the first floor.” Thus, the elevator may have been built for S.C. Hayden & Co. and was in place when F.J. West purchased the building. Alternatively, the elevator may have been installed when F.J. West remodeled the building for its own use. Regardless, it can be confirmed that a passenger elevator was in place and in use no later than September 1891, which makes this elevator at least 122 years old. In May 1912, Park-Brannock Co. (maker of men’s and women’s shoes) purchased the building. Between 1912 and 1926, it is possible to find references to the elevator in Park-Brannock’s newspaper advertisements. In December 1936, the building was sold to Wade Apparel Inc., and the Syracuse American reported the building would be “remodeled for the tenants, and new fixtures will be installed.” Whether these renovations involved the enclosure and “walling up” of the then-45-year-old elevator is unknown. All that is known is that this remarkable unit “vanished” from the official record at about this time, only to be rediscovered by Ritch almost 75 years later (Figure 5).

Once again, I would like to express my thanks to Ritch for his generosity in sharing his elevator with EW and me. I would also like to repeat my request for our readers to share their knowledge of old elevators with EW through the magazine at e-mail: [email protected], and I want to reaffirm my willingness to take “road trips” to document these elevators. I would also ask readers in upstate New York to help identify other existing Houser elevators so we may gain a better understanding of this important regional firm.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.