Control Focus On Cabs And Doors And Safety (With A Twist Of The Wrist)

Sep 1, 2019

A rare case of complexity finding success is described in this historical look at the Randall elevator door controller.

Elevator doors have been a consistent subject of conversation, study and innovation since the late 19th century. These efforts have produced a variety of solutions to the problem of safe door operation over the past 150 years. The ingenuity of inventors during the early 20th century often manifested itself in designs that, from a contemporary perspective, seem overly complex and mechanically impractical. The work of Horatio C. Randall, pursued between 1907 and 1919, falls into these categories; however, this assessment is balanced against the fact that he successfully translated his designs into commercially successful systems employed in numerous buildings. The following is the story of the Randall elevator door controller, a device that offered guaranteed passenger safety “with a twist of the wrist.”[1]

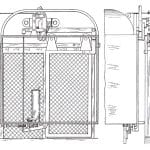

Unfortunately, very little is known about Horatio Randall. He was born in West Middlesex, Pennsylvania, in 1864. Nothing is known about his educational background or early career. He eventually found his way to San Francisco, where he was mid-1890s to 1907. In 1908, he left the world of insurance and founded Randall Elevator Door Control Co. The reasons behind this sudden career change are unknown. (Perhaps it represents a particularly unique midlife crisis.) Randall filed his first patent application in April 1907: “Controlling Mechanism for Working Cylinders,” U.S. Patent No. 971,143 (September 27, 1910). The invention was described as “especially adapted for use in controlling elevator doors” and consisted of a cylinder operated by “compressed air, steam, water under pressure or the like.”[2] His second patent, “Motor for Operating Doors,” U.S. Patent No. 1,060,789 (application filed July 1908; patent granted May 1913), added additional features to his “working cylinder” and included a means to shut off power as the door was opened and a means to operate the door if the cylinder failed (Figure 1).

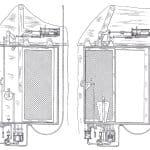

His third patent, “Controlling Mechanism for Elevator Doors,” U.S. Patent No. 997,848 (application filed May 1910; patent granted July 1911), concerned a manually operated system “for preventing the opening of the door, except when the floor of the car is within a certain predetermined distance Randall elevator door pneumatic cylinder (“Motor for Operating Doors” patent) employed as an agent of New York Life Insurance Co. from the from a floor of the building.”[3] When the car approached its destination, the operator pressed a foot pedal that activated a series of levers on top of the car that engaged a mechanism above the shaft opening, which released the shaft door and allowed the operator to slide it open. The movement of the door activated a series of levers in the shaft that engaged a mechanism under the car, which pushed a rod upward into the car controller, preventing its operation (Figure 2).

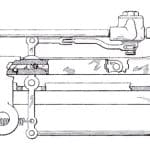

Randall’s fourth patent, “Controlling Mechanism for Elevator Doors and Cars,” U.S. Patent No. 1,080,021 (application filed January 1911; patent granted December 1913), concerned a design that embraced elements of his earlier patents and was his most complex scheme to date. He employed “compressed fluid cylinders” located at the floor landings that opened and closed the shaft doors. Door operation was controlled by a series of devices under the floor. These were operated by compressed air supplied by a traveling “flexible pipe.” To activate the system, as the car approached a landing, the operator pressed a foot pedal. This action first activated a small piston that moved a cam lever atop the car, which engaged the “fluid cylinder” that opened the shaft door and, then, activated a second piston that pulled the car- operating switch down into a locked position. The car also featured a secondary hand control that could also be used to activate the door-opening cam. Additionally, it functioned as a safety lock. Randall illustrated this system applied to both electric and hydraulic elevators (Figure 3).

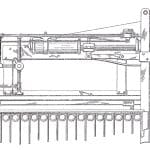

Randall’s next patent, “Fluid Operated Motor,” U.S. Patent No. 1,263,108 (application filed June 1914; patent granted April 1918), focused solely on the design of a pneumatic cylinder to operate the shaft doors. He claimed his new design was:

“. . .particularly adapted to be used in opening and closing elevator doors using compressed air as the motive fluid, but it is to be understood that it is not limited to such use, although in such use, it possesses many advantageous features, such as locking the door in the closed position and retarding the movement of the door as it reaches the end of its throw in either direction, thereby obviating all banging and jarring of the doors.”[4]

The system consisted of a double-ended cylinder that controlled the door’s movement (Figures 4 and 5). Randall displayed a model of his pneumatic elevator door operator at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, held in San Francisco in February-December 1915.

An October 1916 advertisement for Randall’s company claimed his design had been awarded a “Gold Medal” at the exposition. This claim was featured in all subsequent promotional material. The advertisement also revealed the company’s success during its first eight years. It provided a list of 50 installations, which included buildings located throughout California; most of the installations were in San Francisco (10) and Los Angeles (21). The advertisement copy also highlighted the system’s key safety and operational features:

- “Elevator cannot run while any door in the shaft is open. Operator has full control of the door.

- Door can be instantly reversed at any point in opening or closing.

- Does away with all noise due to slamming doors.

- Double locks the elevator from starting when any door in shaft is open.

- Automatically, pneumatically centers elevator control switch before the door can be opened.

- Breaks circuit control switch in elevator when the door starts to open.

- Electric push-button control to open and close doors

- Door can only be opened when the elevator is within six in. of the landing.}

- Securely locks the door from the corridor side.

- Elevator service brought to the highest degree of safety and efficiency.”[5]

Randall continued to improve his design over the next three years. He received two additional patents during this period.

Unfortunately, Randall did not live to enjoy the continued success of his efforts. He died at age 55 on June 26, 1919, three months after he filed the seventh patent application for his pneumatic door operator. However, Randall’s death did not mean the end of his door controller. In late 1919 or early 1920, Randall Elevator Door Control merged with Hydrometric Co. of Los Angeles, and the newly formed Randall Control and Hydrometric Corp. was launched in February 1920. This merger was a strange blend of manufacturing interests. Hydrometric Co., established in December 1916, specialized in the manufacture of the “Reliance Irrigation Meter,” designed for use in “open ditches, reservoirs [and] gravity pipe lines.”[6] The commercial rationale behind the merger of the two companies remains unknown; however, it is of interest that “Randall” occupied pride-of-place in the new name, a fact that speaks to the regional strength of his brand.

The company published an eight-page catalog in the mid-1920s that extolled the virtues of the Randall elevator door controller. The catalog also serves as evidence of its continued development under the stewardship of its new owners. In fact, efforts to improve Randall’s designs began immediately after the company’s creation. In September 1920, William H. Hartman filed a patent application for a design related:

“. . .particularly to elevator control systems employing power-operated means for opening and closing the elevator shaft doors. The power-operated means may comprise any suitable mechanism, and, in the present instance, I have employed a fluid pressure motor. Heretofore, as far as I am aware, it has been the practice to install a fluid pressure operated motor at each floor of the elevator shaft, the motor being connected to the shaft door. In a shaft having 20 shaft doors, such [a] system entails the installation of 20 fluid pressure motors in the shaft. In accordance with my invention, I provide one fluid pressure motor only, which is arranged on the car, and this motor moves into cooperative position with respect to the shaft door and its lock as the car reaches a position opposite a shaft door. Substantially, the entire control and operative mechanism for the door and lock is carried by the car, thus greatly reducing the cost of installation.”[7]

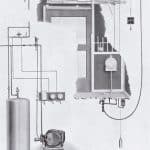

The patent illustrations reveal an improved version of Randall’s 1914 design (Figures 6 and 7). The 1920s catalog included a rendering based on one of Hartman’s patent drawings and an illustration of a complete system (Figures 8 and 9). In new construction, the space required for the “pneumatic operating door engine” was “about” 65 in. in length, with a depth of 4 in. and a height of 17 in.[1] The company claimed the system would “increase efficiency in elevator

service from 15% to 20% over hand operated doors; reduce time in starting and stopping; [and] ensure actual, maximum and real safety.”[1] The ease with which these goals could be obtained was illustrated by the company logo, which featured the slogan “control and safety with a twist of the wrist” (Figure 10).[1]

The company’s success continued throughout the 1920s. A February 3, 1924, Los Angeles Times article claimed Randall Control and Hydrometric’s products were “known all over the country,” noting branch offices in “New York, Kansas City, San Francisco and other cities.”[8] By this date, it had also expanded its product line to include “modern signal systems and hangers.”[8] The success of the 1920s did not, however, continue into the next decade. The last known reference to the company was in May 1930, and while its fate is unknown, it was likely a victim of the Great Depression. While the Randall elevator door controller’s disappearance was as mysterious as its appearance, it serves as a reminder of the ingenuity often found within the vertical-transportation industry.

- Figure 1: (top to bottom): Randall elevator door controller (“Controlling Mechanism for Working Cylinders” patent) and Randall elevator door pneumatic cylinder (“Motor for Operating Doors” patent)

- Figure 2: Randall door operating system[3]

- Figure 3: Randall elevator door controller: (l-r) controller for electric elevators (shaft door closed) and controller for hydraulic elevators (shaft door closed) (“Controlling Mechanism for Elevator Doors and Cars” patent)

- Figure 4: Randall elevator door controller, detail of double-ended cylinder design[4]

- Figure 5: Schematic of Randall elevator door controller[4]

- Figure 6: Pneumatic elevator door controller, detail of double-ended cylinder design[7]

- Figure 7: Pneumatic elevator door controller[7]

- Figure 8: Randall elevator door controller[1]

- Figure 9: “Randall standard pneumatic elevator door control with air cylinders above door, master switch, safety interlocking system, operating hand lever, cam, etc. showing motor compressor, receiver, valves, etc.”[1]

References

[1] Randall Control and Hydrometric Corp. Randall Elevator Door Controls, Los Angeles (c. 1925).

[2] “Controlling Mechanism for Working Cylinders,” U.S. Patent No. 971,143 (September 27, 1910).

[3] “Controlling Mechanism for Elevator Doors,” U.S. Patent No. 997,848 ( July 11, 1911).

[4] “Fluid Operated Motor,” U.S. Patent No. 1,263,108 (April 16, 1918).

[5] “Randall Elevator Door Control Company Advertisement,” The Architect, V. 12, No. 4 (October 1916).

[6] “Hydrometric Company Advertisement,” California Cultivator, V. 50 (March 30, 1918).

[7] “Elevator Control System,” U.S. Patent No. 1,444,313 (February 6, 1923).

[8] “Accessory Form Takes New Space,” Los Angeles Times (February 3, 1924).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.