Educating Maintenance Mechanics

Oct 1, 2019

The need for new mechanics to be trained on older equipment should not be ignored.

In 1980, the vast majority of traction (electric) elevators were Ward Leonard motor control, and direct-acting hydraulic elevators dominated the market. Today, solid-state motor controls and machine-room-less elevators have displaced those industry offerings. The advance of new technology and the explosion of modernization projects since the market recovery turned the fortunes around in the building industry have changed the equipment mix. Additionally, there has been a noticeable turnover of elevator personnel: those who installed and maintained the old equipment have retired, replaced by younger personnel who grew up on the new equipment. This has created a disconnect in knowledge, as there is still an inventory of old equipment and no training of the new mechanics. It was mentioned at the International Association of Elevator Consultants Annual Forum that obsolescence included a lack of experienced and trained personnel. This month, we should examine this issue and identify solutions to this widening gap of knowledge and equipment.

Maintenance Guidelines

The National Elevator Industry, Inc. (NEII) describes the expectations of elevator and escalator/moving-walk maintenance. There are elevator control system and electric elevator mechanical condition and adjustment maintenance specifications written in NEII-1 Parts 10 and 11. Written by NEII and published in its Building Transportation Standards and Guidelines, it is, by definition, the industry standard for reference. The minimum standard is that acceleration and stopping should be smooth.

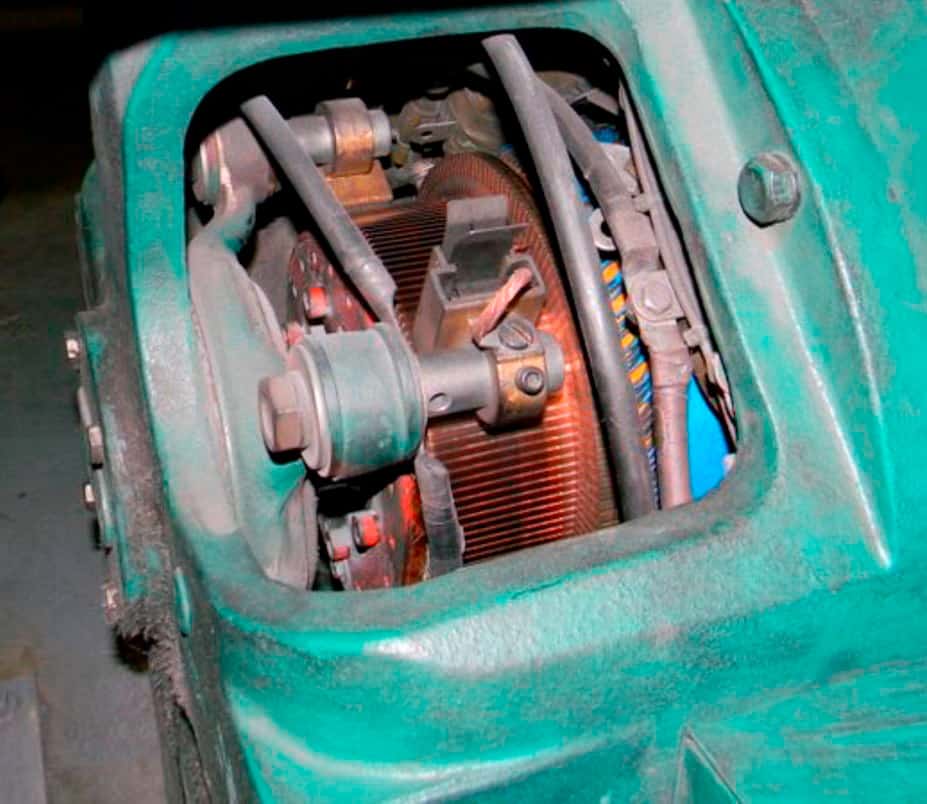

Consultants write specifications regarding such metrics as acceleration rates, jerk-rate limits, ride quality, horizontal accelerations, sound limits and stopping accuracy, for example. These have been specification staples of the industry for decades. This was possible to achieve for generator systems using Ward Leonard controls, as shown by their century of use prior to the advent of solid-state motor controls. Yet, we are seeing an increase in loss of control, jerky motions and misleveling and a decline in maintaining smooth acceleration and stopping. One reason for this increase is loss of motor-generator control, due to lack of fundamental motor-generator maintenance, megging the armatures and keeping the resistance above manufacturers’ specifications (typically over 1 megohm).

There is a loss of knowledge that includes not knowing what a megohm meter (megger) is and the negative effects of shorted armatures. The problems usually stem from carbon dust accumulation impregnating the armature and causing shorts in the windings. This can be exacerbated by high humidity, high temperature and less-frequent visits to clean the carbon dust out of the system. Correct carbon brush selection is key to prevent excessive dusting, the primary contributor to this effect.

These effects are being reported to consultants and, when looking at equipment, it is visible when the machine room is covered by uncleaned carbon dust. Proper commutation is a critical element; seeing anything but a chocolate-colored commutator with minimal sparking means there are system issues that must be addressed. Brush length is critical. The embedded pigtail touching the commutator due to allowing a brush to wear too low is absolutely preventable and should never occur. Series field controls and suicide circuitry must be fully understood by the maintenance mechanic to ensure safe operation. The control of the loop circuit power and basic motor function is totally different compared to that of solid-state motor control, and these fundamentals are not being provided after the National Elevator Industry Educational Program or Certified Elevator Technician (CET®) program is completed.

The justification being presented is that the companies can’t successfully bid these higher prices and, therefore, don’t provide enough labor time to do a proper job. This seems to be counterintuitive. We all agree these older systems need more time; the customer should be presented with bids that reflect this reality; and, if a company goes low on price to get the job on maintenance, the owners will suffer the consequences of their oversight. The number of contractors who successfully bid the job at lower prices and are not knowledgeable of the work that needs to be done appears to be on the rise.

A secondary effect is more disturbing: the higher costs are being charged to the customers and are being paid, but labor scheduling limits the time a mechanic is allowed to do maintenance. This is then used to justify and motivate a modernization, but, in some cases, not until the hazard has injured building users. This occurs when smooth acceleration and stopping, symptoms that typically populate a string of callbacks, are long gone.

When a job is bid, all maintenance contracts written by consultants require some equipment qualifications of the company, but proving experience in the type of equipment is not being required. Generally, a minimum of five years of type experience is in the contract language. Even company contracts claim they will provide qualified personnel. If this is the case, maintaining the equipment pursuant to industry standards should not allow the degradation of the equipment that is being observed.

Companies should observe when the experience in type is not there and begin a training program to ensure new mechanics are at least educated on how the older systems work. This is not occurring; there is, instead, a reliance on callback training. This practice is non-defensible. Training in 1980 at Westinghouse was mandatory in San Francisco. We had weekly education from different adjustors, and the company bought pizza for the attendees. Two-hour classes in which any employee could show up and learn to the extent they wanted were held. This was also the practice by Amtech in the 1990s. Somewhere, these opportunities have stopped, displaced by important safety meetings, but nothing in the way of technical training; at least, in the matters with which I am familiar. If your company does technical training, I applaud you, and this should be the opening statement when bidding jobs.

Conclusion

Training is the answer. Educating new mechanics on older equipment must be kept a priority until the older systems are completely modernized. This was the standard for many years and should be adopted by every company working on this equipment. Measuring the callbacks and analyzing the root cause should be the practice when determining the topics of instruction. Using adjusters and older mechanics familiar with these systems as teachers should be encouraged to cure this issue. Until mechanics are trained, believing this will come from experience alone will allow continued problems, including injury hazards, to exist in the industry. We must all be aware and take actions to eliminate the education divide.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.