I couldn’t decide what to write for my column this edition. There are two subject matters that have been bugging me, so I have decided to cover them both. My basis for doing this is that they are both equally important, and I couldn’t decide on primacy for one or the other. I might regret this when it comes to Issue 111, and I am scratching around for something to write about!

Necessity is the mother of invention, so they say, and many have written about COVID-19 and the way it affects lifts and escalators. The Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers (CIBSE) is the natural home when it comes to Professional Engineering Institutions for lifts and escalators. It is well known for its very active specialist lift group, and also for what I consider to be one of the best books about transportation systems in buildings, known as Guide D.

After the outbreak of the pandemic, two guides were issued by CIBSE relative to lifts and escalators and COVID-19. One was about the recommissioning of lifts and escalators as buildings became reoccupied, and the other was about occupancy of lifts. The latter being a subject that I think will rumble on for years, given people’s anxieties about protecting their personal space being ramped up by the pandemic.

That is no criticism of people, but it does affect the way building and lift designers think: The same way, I believe, that the eventual publication of the Grenfell Tower report will make people think very differently, but, for now, it’s people’s personal fear of catching something that is up there in my mind.

This leads me into escalator handrail hygiene. For years, we have had standards that prevent us from putting anything near a handrail for fear of entrapment, especially with fingers or clothing.

Accidents on escalators aren’t new, and I was alerted many years ago to Dr. Campbell-Reid of Sheffield, who published a paper on escalator hand injuries. I thought that, perhaps, this was a one-off paper by a medical person, so I searched the indexes of the well-known medical journal “The Lancet” and was surprised to find no less than nine papers written by people from outside the escalator industry proper.

Having witnessed a number of UV devices fitted to escalators in the U.K. that were exposed to the boarding passenger, I was immediately reminded of an accident where a lady was strangled when the free-flowing clothes she was wearing got caught in an escalator handrail in Hounslow, West London. A headline from a U.K.-based newspaper also reported on an incident in the U.S. (Figure 1).

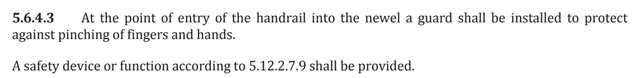

Yes, he had been out and had a drink, but this is foreseeable, and it’s why the EN 115 standard lists significant hazards in section 4. This refers us to specific clauses, and with reference to the subject matter in particular, it is stated in Figure 2.

So, why then install a UV device in a position where someone’s finger or their clothing could get caught? I did a bit more research and was pleased that the Lift & Escalator Industry Association (LEIA) guidance on the matter was very specific that these UV devices should be installed in the truss area away from passengers, which a simple risk assessment would tell you reduced the risk to ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable) status.

Anyway, my second irritation since my last column was an operative in the lift industry who tells me they are a lift engineer. You will be pleased to hear that I am not intending to reignite the debate about the use of the word “engineer.”

The fact is that this person has been trained and put through an apprenticeship on one product. To my mind, that doesn’t make you a lift engineer. A lift engineer should know about the range of drives available (traction, hydraulic, etc.) and not just one product, in my opinion. I fully accept that there are areas of lift engineering that are specialist areas, such as traffic analysis, call handling algorithms and so on, that an installation engineer doesn’t need to know but a designer does.

My problem comes when installation engineers move into areas where they haven’t been trained — for example, an old engineer decides to move onto a service route as they feel they are too old to be carrying control panels upstairs anymore (I am being pragmatic; I am sure you agree). That engineer, having been trained on one product, may then face a whole variety of lifts they have never seen before. Let’s say the engineer had been trained on installing traction machine-room-less systems and then is faced with a hydraulic lift that has broken down. How does that person then claim to be competent, and for that matter, how does his or her employer satisfy the legal requirement to ensure this? Just asking and, as usual, I’d welcome your views.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.