Today’s best practices call for frequent technician visits and following the MCP.

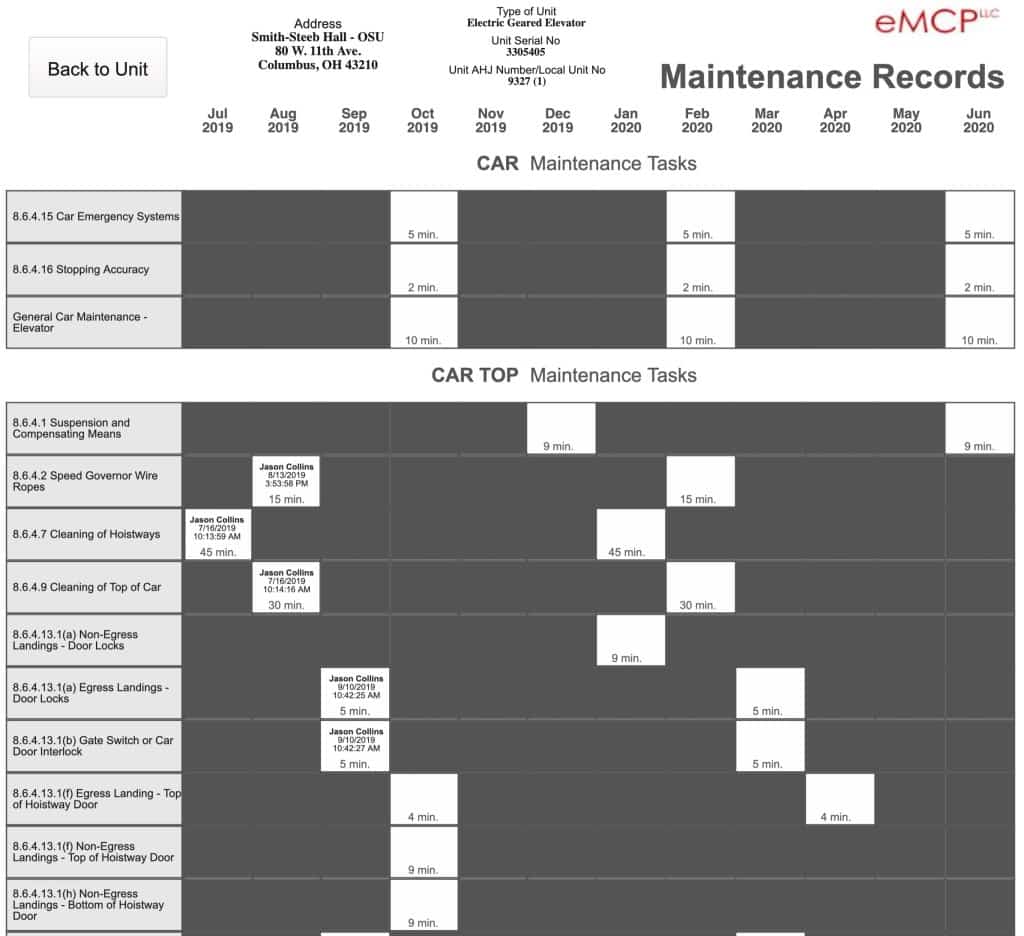

In 2000, the ASME A17.1/CSA B44 Safety Code for Elevators and Escalators added significant changes to require maintenance, require that maintenance task-completion be recorded and that these and many other records be available for inspection. In 2002, the code added the requirement that this system be called a Maintenance Control Program (MCP). All U.S. and Canadian jurisdictions now follow an edition of the code requiring an MCP. In addition, the code made it retroactive, applying it to all units, new and existing. This is an important distinction and is a recognition of the importance of the MCP for the safety of life and limb, the purpose of the code. AHJs in the U.S. and Regulatory Authorities (RAs) in Canada are enforcing these requirements with increasing regularity. Is this a good thing? What are the main elements of an MCP?

Hazard Reduction

No conversation of vertical-transportation (VT) equipment should be engaged without an understanding of the hazards associated with these devices. Elevators are automatic ascending devices in which riders simply tell the car where to go. No other input is allowed or provided to control the accelerations, velocities or stopping of the car. Opening and closing the doors must be managed by a scrutinizing safety system to prevent exposure to the hazard of a car moving with the doors open. The lower terminals are solid concrete, and when the car is moving toward the terminals, assurance that the velocity is limited so the car doesn’t crash into the pit or upward into the overhead must be provided by dependable safety systems and subsystems. These and several other hazards are present with every run.

Escalators are fraught with hazards, too: clearances must be kept to a minimum on the moving components, and ensuring the combs stay meshed, the step treads are not being honed to a knife edge, the handrails are intact and moving, the skirts are properly lubricated and the gap between the moving step and stationary skirt is below code-required minimums (to prevent side-of-step entrapments) are all matters that should be routinely addressed.

As an industry, it could be said we have done a statistically good job. There are an estimated 49 million rides every day on more than 1 million units in the U.S. and Canada[1] (18 billion rides over 365 days). This indicates proper design and maintenance can ensure systems, subsystems, functions and components are satisfactorily functioning to prevent hazards. When maintenance is not done, hazards increase, as shown by the continued number of incidents we see in the industry that are not related to rider abuse. Code-writers recognized this and wrote the maintenance section to convert their experience into requirements to perform and record maintenance, repairs, replacements and testing to reduce incidents.

A hazard can result in a fatality when the most-dangerous events occur. This, therefore, requires the highest attention be given to the critical items for which failure can create the hazard. The MCP is the document that identifies the critical items of VT equipment that must be maintained to assure the hazards do not occur. But, more than simply listing the items, the code also details the specific techniques to determine the frequency of maintenance; that is, the interval at which a task is performed. It further requires the tasks be identified and the procedures be provided to the elevator personnel who will be maintaining the item. Finally, it requires that records of these tasks be created and available to elevator personnel. Some records are required to be available onsite, while others are allowed to be provided offsite or be made available electronically.

The importance of the MCP is critical, and any MCPs that fail to meet the minimum code requirements should be called to task and corrected. Several MCPs are noncompliant for the following reasons:

- If the tasks are not mandatory in the MCP — that is, if the tasks can be left undone without notice — then it is not consistent with the intent of the MCP that the tasks get completed.

- If an MCP does not clearly identify the intervals between tasks, it does not meet the literal requirements of the code.

- If there is no analysis of the usage, age, condition, environment, quality, technology and accumulated wear of the unit to determine the interval, then it does not meet the literal code requirement to do so.

- If the site is not visited monthly, the opportunity to hear, see, smell or feel a developing component failure is lost. Monthly visits are typically required in consultant-written contracts but not so often with company-written contracts. Not visiting monthly exposes all the risks noted and allows such degradation of equipment as seals leaking lubricating fluids out of gearboxes, dirt and debris accumulations causing early failure of bearings and sliding components and important door equipment vibrating off. Customers cannot always hear or see these failures, so it is imperative for the maintenance company to check with more regularity than quarterly or twice a year. If there is no MCP, tasks can, and likely will, be overlooked.

In addition to the safety hazards associated with a lack of maintenance, early equipment failure will also be a result of poor maintenance. For example, with monthly maintenance visits, an oil leak would be obvious and tended to before a gear runs dry and requires replacement. Owners have been charged extra for failures due to inadequate maintenance. For example, a door gets banged by a user, bending the gib and causing the door to scrape until the door skin requires replacement. This could only occur if the maintenance company chose to go to the site no more frequently than every six months. Had it gone monthly, the maintenance technicians would have likely replaced the bent gib and prevented the continuing damage to the door.

The MCP references code-required components but not all the maintenance items. For example, push-button lights are not required by code to be replaced if burned out; that is simply good maintenance, so all MCPs should include them. A visual check of every lamp at least once in a while to assure they work is a good practice. It is a screaming beacon of poor maintenance to see the position indicators not displaying correctly. Doors opening fully so that carts don’t hit them is also a result of good maintenance.

Conclusion

We have a statistically low number of significant injuries, but that number, due to equipment failures, should be zero. We have designed safety systems, reliability and, maybe, minimized maintenance-intensive components, but not all systems are new and designed with these safety systems, so the technology of the older systems requires more attention. In short, the code writers recognize maintenance is absolutely necessary and that each unit must be evaluated, and its maintenance verified with clear records. It is a good thing, and owners and their consultants are encouraged to challenge their maintenance contractors to show how they comply with the Maintenance section of the code.

Reference

[1] NEII Data Elevator and Escalator Fun Fact

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.