Even those with relatively high levels of training and education can be sidetracked.

This issue of ELEVATOR WORLD UK focuses upon training and education, and I might share an experience from early in my career which highlighted aspects of management theory and which throws a little light upon the psychological barriers which can operate to frustrate even relatively high levels of training and education.

At the end of 1987, I had transferred “off the tools” (to quote the term prevalent at the time) to become a full-time pen-pusher.

I was assigned to shadow a colleague to learn the ropes, and we attended a construction project meeting which involved an extended professional design team which included architects, civil engineers, structural engineers, quantity surveyors and project and contracts managers. The project involved the addition of a sales floor to a high-class department store. The client required that the store should continue trading during the works.

Our role involved the upward extension of the existing passenger lift to serve the new sales floor. The lift served three existing sales floors and was of traditional traction two-speed design, with 24-person capacity and a motor room located directly above the lift shaft. The existing 1970s lift equipment was to be retained and reused.

The design team, by way of information provided by the quantity surveyor, had determined that the lift would be retained in operation throughout the works, be extended upwards over a weekend and returned to the client for use on the following Monday morning.

My colleague explained that this was unrealistic and that a site programme in the region of six weeks or more would be required for the lift works alone.

A protracted discussion arose. The design team, and particularly the quantity surveyor and architect, argued vociferously in support of the single weekend programme, insisting that this was achievable. My colleague argued that the programme was, in fact, impossible.

As discussions progressed, people became more entrenched in their views and insistent in their support of the impracticable programme, eventually to a state of agitation and frustration in relation to our refusal to accept this. The discussion degenerated to the extent that veiled threats of “finding an alternative contractor” emerged. As the original equipment manufacturer and the client’s preferred contractor, my colleague stood his ground, albeit that the effect was to further agitate members of the design team, such that the civil engineer, who was leading the design and construction, embraced the weekend programme mantra such that the whole team was now in support of what was a wholly unrealistic proposition.

My colleague, applying his experience coupled with an element of a lateral thinking, relented and agreed, explaining as follows:

“Yes, OK, we will undertake the works over a weekend as you require. We will attend on Saturday evening and electrically disconnect the lift equipment, lower the lift car and counterweight into the pit and relocate the lift machine room equipment to a designated storage point. Then, on Sunday, you can construct the additional sales floor, extend the lift shaft upwards and construct the new lift motor room on the new roof. We can then return on Sunday evening, install the lift motor room equipment, extend the guide rails, install the new landing entrance and fixtures at the top floor, install new ropes and a new floor selector tape, install the electrical wiring, make all of the control modifications, and then commission the lift, all ready for use on Monday morning.”

I doubt I’ll ever forget the expression on the face of the civil engineer as he struggled to internalise this information, whilst staring intently at the quantity surveyor. I thought to myself, I know what he is thinking (the content of which is inappropriate for publication in EW UK).

I was amazed at how readily a design team of such experienced and highly qualified construction professionals could be persuaded, and was able to convince itself, that a proposal, which was, in all practicality impossible, and requiring of a works programme of several weeks, could be executed over a couple of days. Needless to say, we received our purchase order, which was based upon our original proposed works programme.

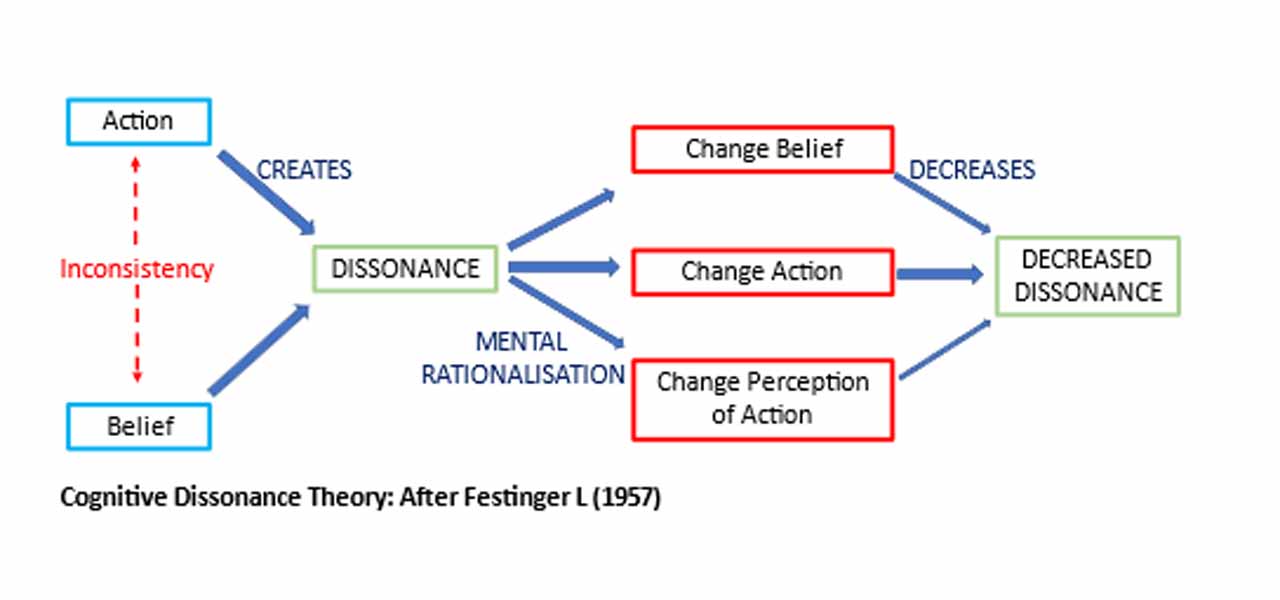

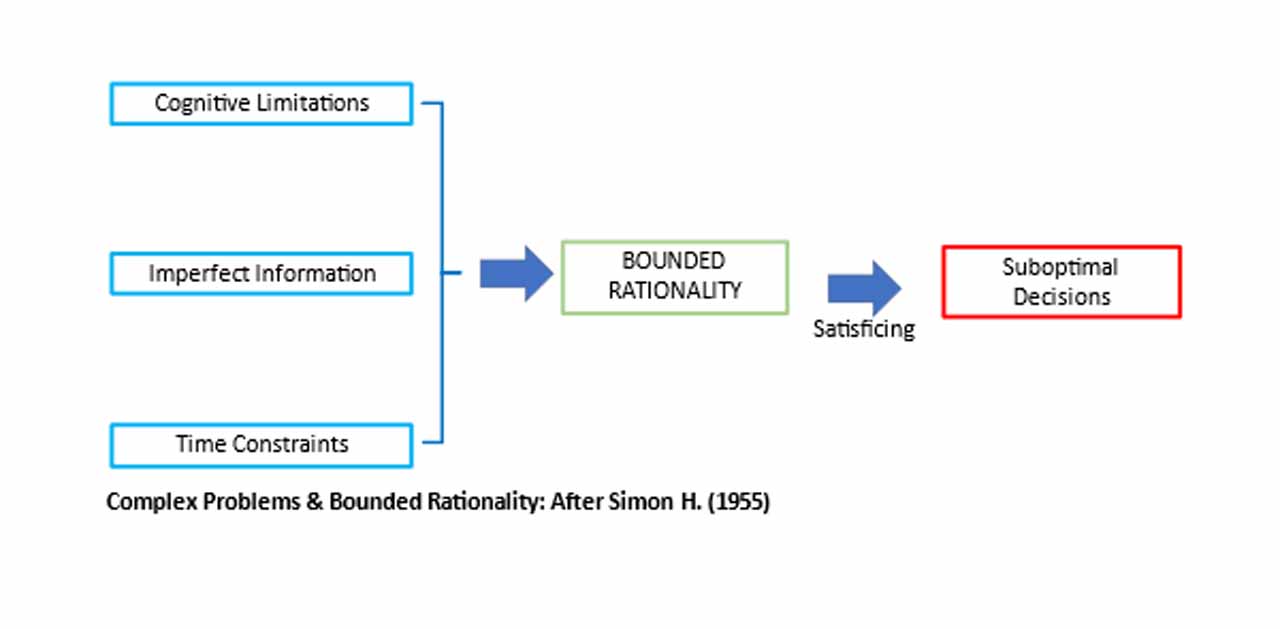

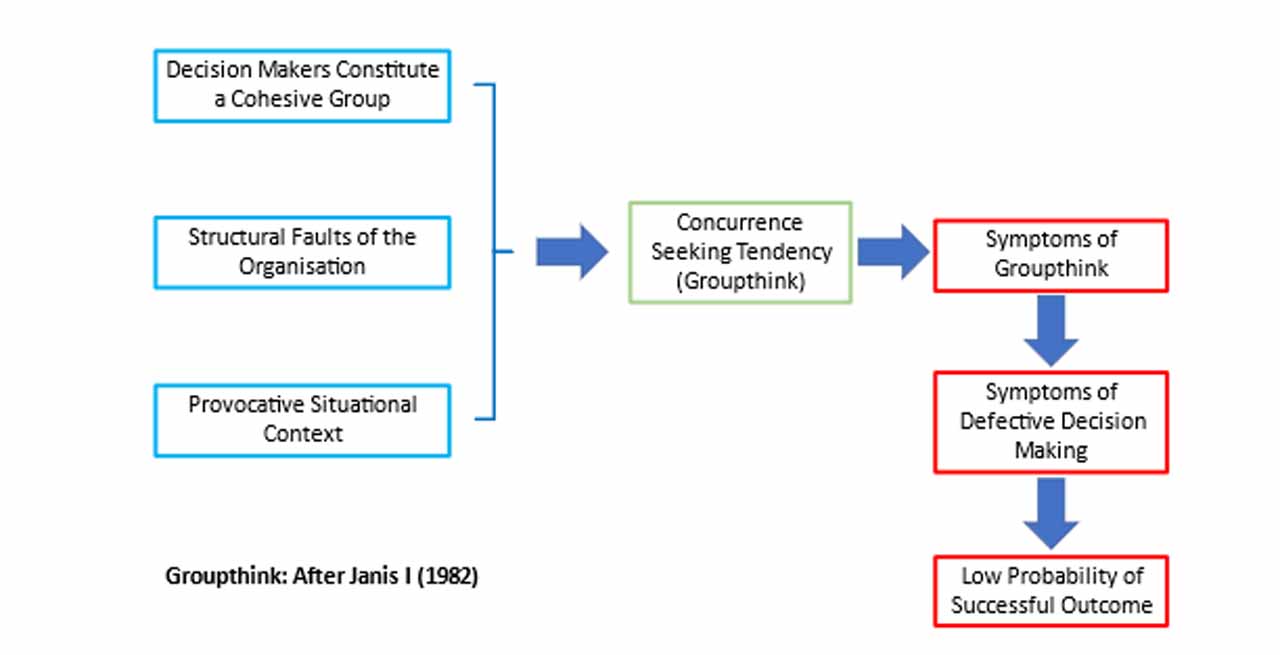

The academic “Management” view of such events involves concepts drawn from social-psychology including those of Cognitive Dissonance, Bounded Rationality and Group Think.

Cognitive Dissonance (conceptually modelled in Image 1) relates to a situation in which a person holds conflicting attitudes, beliefs or behaviours which operate to produce a feeling of discomfort leading to an alteration in one of the attitudes, beliefs or behaviours such as to reduce the discomfort and restore harmony. Here, a belief that the lift works could be completed over a weekend had become sufficiently ingrained in the minds of the team members, to the extent that no level of reasoned explanation could dislodge this false perception, and the discomforting feeling tended to reinforce the ingrained misconceptions.

Bounded Rationality (conceptually modelled in Image 2) relates to decision-making processes and the way in which the rationality of a decision is bounded by the information available, by the cognitive capacities of the decision makers and by the finite amount of time in which the decision must be made.

Group Think (conceptually modelled in Image 3) involves a phenomenon in a group of people in which a desire for harmony or conformity in the group exists results in an irrational or dysfunctional decision-making outcome.

The effect of these psychological phenomena is such that we come to believe something, regardless as to how irrational or ridiculous this may be, and then proceed to internalise and justify that belief such that any attempt to dislodge or challenge it is perceived as an attack on the ego or integrity of the individual.

In order to overcome this dissonance or mental blindness, my colleague had employed an approach based upon the use of narrative — that is by way of a storyline explanation of the steps required in order to complete the works, as opposed to the design team’s narrow focus upon a desired outcome. The effect of this approach was to force the listener to mentally consider the detailed process and steps required to undertake the works. This detailed mental consideration forces the listener to rationalise the proposition under consideration, sowing doubt in the mind of the listener, which initiates further mental wrangling, eventually causing the listener to question the entrenched belief, in this case driven by an underlying pressure to achieve the client’s desired outcome, that the works could be completed over a weekend.

I learned at an early stage how readily even the most well-qualified professionals and managers may be misled or may be apt to mislead themselves due to the external pressures which arise in relation to commercial activities.

This use of a narrative approach required that the listeners should logically consider and rationalise their beliefs. And, on the basis of this rationalisation, revise these beliefs, such that the decision to forego the errant, but previously strongly held, belief, was internalised by the individuals, to an extent that had proven impossible by way of external persuasion. The effect is such that ego-driven aspects of who is right or wrong and/or in control of the decision-making process are rendered secondary, and rational and reasoned common sense is re-established.

So, regardless as to the gripes I encounter as to the technical and managerial competence of our industry management, I learned at an early stage how readily even the most well-qualified professionals and managers may be misled or may be apt to mislead themselves due to the external pressures which arise in relation to commercial activities, and in addition was able to observe a good example of management theory being played out in practice.

In a 2019 Harvard Business Review article, Professor Kuh of Indiana University considered the tension between short-term vocational training (which employers promote to address immediate needs) and the plethora of certificates, badges and similar which accompany this, and that of a traditional, but more protracted, educational experience. Kuh also notes the contrarian management rhetoric which bemoans reports of college graduates who are, in their view, unable to communicate coherently in writing, explain complex problems or handle working in different cultures.

In this respect, Kuh recognises that there are no short-cuts to cultivating workers who are able to meet the demands of the 21st century workplace (which can only increase in its complexity) and the absurdity underlying the rhetoric which attempts to reconcile the competing demands of “now” over those of the future and how such approaches eventually short-change all of those involved and the wider economy. I believe Kuh’s analysis to be accurate and would welcome the development of structured career paths within our industry through field engineering, design and management disciplines. The basic components are already in place in the apprenticeship schemes, EPAs and courses offered by CIBSE (Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers), the Lift and Escalator Industry Association and the University of Northampton in its MSc and other high-level education programmes. These just need joining-up such as to produce a structure to generate the industry managers and leaders of tomorrow, who should be adept in both the technical and commercial aspects of the industry, which is relatively rare at the moment.

Some of the criticisms of industry management are undoubtedly pertinent, if only rarely constructive. Others are little more than whining, or perhaps reflective of our national preoccupation with harking back to some illusionary utopian past. Having an active interest in the practice of “Management,” I find the varying perceptions of our industry management interesting and am led to reflect upon how things might be improved.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.