Response to “Voluntary Egress Elevators”

Feb 1, 2020

Your author feels important points need to be presented regarding emergency evacuations.

by Giuseppe Iotti

The article “Voluntary Egress Elevators: Enhancements to the 2004 CTBUH Guideline” by Johannes de Jong (ELEVATOR WORLD, December 2019) was quite interesting, but there are points that deserve to be discussed in his description of the situation in Europe.

The first is the author’s interpretation of the purpose of the document CEN/TS 81-76, on lifts for the evacuation of disabled occupants from buildings. He seems to take for granted that the use of these lifts should be supervised by firefighters, but firefighters often complain about this because it distracts them from their main task, which is to save the building, thus also saving the occupants. In my opinion, this is a misunderstanding, because the text of the standard identifies other figures — “evacuation assistants,” apart from firefighters— who should supervise the operation of these facilities in the event people with disabilities must be evacuated. This trained staff is understood to reside in the building. This is why they should intervene at the first warning, presumably before the firefighters have arrived.

It might be that firefighters feel this interferes with their duties because these lifts are not available to them, as perhaps they would deem appropriate. However, in a building with lifts that can be used for the evacuation of the disabled, I think there also should be lifts compliant with EN 81-72 (that is, “for firefighters”), which are intended only for use of firefighters. If this type of lift is not available, it should be the building designers’ responsibility — not dependent on the fact that the document CEN/TS 81-76 exists and is more or less valid. Regarding the EN 81-72 standard for firefighter lifts, we see that it requires 630 kg as the minimum capacity of the cabins, a rating judged as too scarce by some fire departments.

We all know the average height of tall buildings in Europe is lower than that in other areas, particularly the Far East. In most cases, the height is such that the firefighters can intervene from outside with their ladders, which, in many cases, is preferable for their own safety. For the most part, firefighter lifts are not even installed in these buildings, though, in any case, this depends on national or local regulations.

In cases where the height of the building is such as to make the presence of firefighter lifts necessary, it is up to the building designers to incorporate an adequate system of lifts that, presumably, takes into account the actual needs of safety, so that the intervention of firefighters will be quick and effective. EN 81-72 gives only minimum standards, which should not be interpreted as a loophole that allows less investment in building safety.

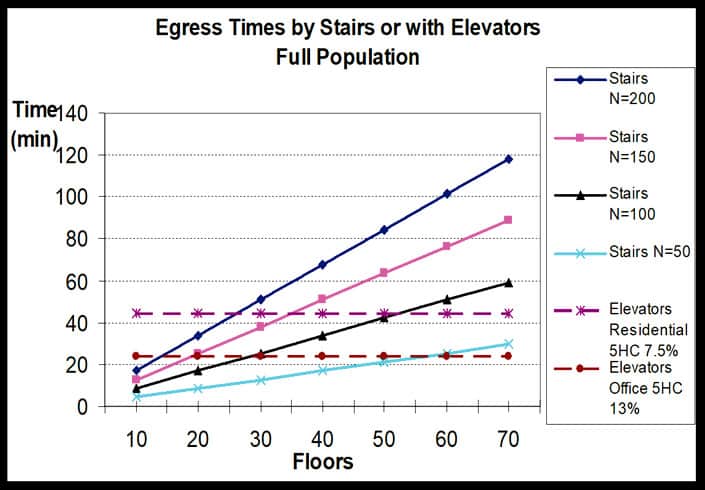

I then come to the article’s very interesting Figure 5, which shows estimates of the evacuation times by stairs or by elevators, in two hypotheses of adopted elevator systems. We can deduce from this figure that, up to 50 floors, and up to 100 people per floor (which means a maximum population of 5,000people), evacuation times are lower using the stairs with both hypothesized elevator systems.

In such a high-rise building, for people with limited mobility, there should be one or more means, regardless of compliance with CEN/ TS-76, that can take them out safely. This should be accomplished without supervision from firefighters (as they may not be able to intervene immediately because they have to focus on something else), but instead from “assistance teams” of building residents specifically trained for this. The technical solution for these teams to work within the necessary time should be the use of “protected elevators,” which are well illustrated in the article.

De Jong then makes an interesting examination of tall- building evacuation times on which I offer an observation. We are fortunate that there have been very few truly catastrophic events in tall buildings. We must give credit to the designers and builders, as well as to the firefighters and rescue teams who have responded to emergencies, often displaying heroism in their efforts. In some cases, however, the design and construction of the building proved to be lacking.

This lack of concrete experience makes it difficult to evaluate the actual evacuation times of buildings. Practice tests are worth little: I remember seeing a video showing an evacuation test of the Petronas Towers during which people paraded out of the building and even smiled. On the other hand, a realistic exercise cannot be organized, because if people were to behave almost like in a panic — assuming it could be realistically done — they would risk accidents and injuries.

In the most tragic case, 9/11, about two-thirds of the occupants of the World Trade Center Twin Towers managed to save themselves by leaving the buildings before they collapsed, which can be considered a success. The remaining occupants who died were either on the floors directly hit by the aircraft, or above the affected floors and, presumably, could not have used any means of evacuation. It is, therefore, impossible to make exact evaluations of how long it would have taken for everyone to evacuate the buildings under circumstances that would have allowed it. (In this case, I did not consider it necessary to provide exact figures and times, because the scale of such acts of terrorism inhibits the ability to make precise general considerations.)

A more “classic” case occurred in 2010, when a 28-story residential building under renovation in Shanghai caught fire. The building housed about 440 people, and the fire claimed 58 victims — 13% of the occupants. We could say the evacuation was relatively successful, considering the fire had broken out on the 10th floor. Among other things, the building housed many elderly.

In a very tall building populated by thousands of people, actions that offer a great ability to prevent catastrophes should take precedence over those aimed at addressing such events — even if corrective actions are taken into account, including the installation of lifts suitable for evacuation.

In São Paulo, the 24-story building Wilton Pais de Almeida caught fire in 2018, and collapsed within 90 minutes. Though built in 1968, by the time of the fire, the structure had degraded to the point that it was abandoned, and occupied only by homeless people. Of the 372 people inside, only seven died. The evacuation— presumably using the stairs, since a building in such a state of disrepair was unlikely to have working lifts — was almost total.

In the case of the Grenfell Tower in London, 365 people resided in the 24-story residential building (15 per floor, on average) when a fire broke out, claiming 72 lives. The fire started in a fourth-floor apartment that was separated from the common space by a fire-resistant door. The tower’s lifts lacked special fire-protection features and were unsuitable for evacuation; the building had only one stairwell; and there was no centralized alarm system. There was only one entrance/exit door; fire extinguishers had not been maintained for years; and there were no sprinklers. Firefighters promptly arrived and asked the occupants to stay in their apartments. Smoke quickly spread to the stairwell. This prevented many occupants from using the stairs. In any case, they were told to stay in their apartments, which were considered protected. With great difficulty, the firefighters climbed the stairs and managed to save some of the people who were still in their apartments. The order to abandon the “stay put” strategy was given almost 2 hr after the start of the fire, and from then only 36 people were saved.

In cases where the height of the building is such as to make the presence of firefighter lifts necessary, it is up to the building designers to incorporate an adequate system of lifts that, presumably, takes into account the actual needs of safety, so the intervention of firefighters will be quick and effective.

Apart from the Twin Towers, all these cases occurred in relatively short (24-28-story) buildings with relatively low populations. Figure 5 accompanying de Jong’s article, however, does not make significant assumptions about these evacuation times, as there are no cases shown in which the buildings have fewer than 50 occupants per floor. It can be assumed that buildings with heights and populations of this order can, under “normal conditions,” accommodate a complete evacuation in less than a quarter of an hour, mostly by using stairs. The point, however, is incidents of the kind discussed here almost always occur under non-normal conditions. Above all, these buildings were in less-than-optimal conditions — in two cases, economic housing with insufficient safety conditions, and in the Brazilian case, an officially abandoned building.

The fact that, with few exceptions, catastrophic events have occurred mostly in relatively short buildings, rather than in the world’s more-than-3,000 true skyscrapers with heights greater than 150 m, obviously derives from the fact that there are many more of the former, but also because the latter are almost never cheap constructions, so investments in safety must be there — especially against the risk of fire. Among these safety measures is a system of stairs and elevators that allow the entire population of the building to be evacuated within a reasonable amount of time. We can discuss what is “reasonable,” but I don’t think it should exceed 1 hr. Considering Figure 5 of de Jong’s article, the table tells us that buildings with a population of more than 4,000 people and more than 40 floors cannot ensure an evacuation time within 1 hr using only stairs.

However, ensuring that a lift system considered adequate is able to function during a catastrophic event for at least 1 hr (and, thus, contribute to an evacuation strategy) does not seem easy. Therefore, in a very tall building populated by thousands of people, actions that offer a great ability to prevent catastrophes should take precedence over those aimed at addressing such events — even if corrective actions are taken into account, including the installation of lifts suitable for evacuation. Preventive actions of this kind are, for example, applicable to the seismic case, possibly adopting EN 81-77 for the lifts, but, above all, the building should be designed to withstand a seismic event. If the building does not collapse, then, as we say in my language, “All the saints help.”

In particular, among the possible dangers to be considered are acts of terrorism, such as in 9/11, although their “if,” “where” and “when” cannot be predicted. Let us think of the September 14, 2019, attack on the Saudi Aramco refinery by missiles or drones: fortunately, its object was not a high-rise building populated by people, so perhaps it should be defined more as an economic guerrilla act than as “classic” terrorism. It is true that insurance companies will not cover the risk of war, but this is not a good reason to design buildings that, by their nature, are particularly vulnerable in the face of such risks.

From this point of view, one wonders how safe very high buildings can truly be and if it is important to give these risks more consideration beyond the economic and prestige advantages that come with building so tall. In the context of the whole building, it is important to be aware of how effective lifts can be when used as accessories to stairwells in evacuating people within reasonable times, no matter which technical choices are made regarding their protection and mode of operation.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.