The Montmorency Escalator in Le Havre

Dec 1, 2021

In this History article, your author describes an early 20th century French transportation system.

In the early 1920s, the city of Le Havre, France, began the search for an urban transportation system to link the Frileuse Plateau with the Graville District, a problem that included a vertical rise of 48.8 m and a diagonal travel distance of 178 m. The Plateau housed a rapidly growing population of workers who were primarily employed in the Graville District, and city leaders recognized the need to build a transportation system that could navigate the difficult topography and provide rapid and efficient service. It was also recognized that, in addition to passengers, there was a need to accommodate the traffic of bicycles and small wheeled carts and carriages. The normative solution to this type of problem would have been to build a funicular, but it was quickly determined that this type of system would not have the operational speed or capacity required to meet the public’s needs. While escalators were understood to be the best solution for quickly moving large numbers of people between two levels, employing this technology to solve an urban transportation problem had never been attempted. This lack of precedent did not deter Le Havre’s leaders, however, and in 1924 they engaged Edouard Louis Hocquart to design the world’s first urban escalator.

Hocquart had designed escalator systems for the Bon Marché department store (1906) and the Gare d’Orsay (1907) (ELEVATOR WORLD, May 2018), and he had designed the first escalators used in Paris Metro stations (1909 to 1924). Thus, he was the obvious choice to undertake the Le Havre project. Work began in February 1924, and the system was placed into service in May 1928. The lengthy design and construction time was necessary due to the project’s size and complexity. The French patent record provides insights into Hocquart’s design process. He submitted his initial application, titled Escalier mécanique élévateur er descendeur (Ascending and Descending Escalator), on December 24, 1924. The patent was officially posted on December 18, 1925 (French Patent No. 589,503). While waiting for the patent to post, Hocquart filed an addendum on March 6, 1925. The addendum was posted on August 26, 1926 (French Patent No. 589,503/30,227). Both patents were filed by Hocquart and the Société Anonyme des Anciens Établissements Grosselin Père et Fils.

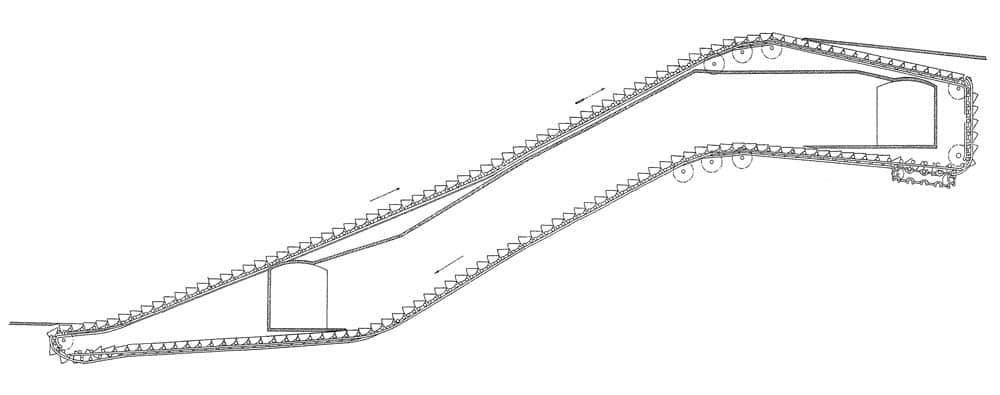

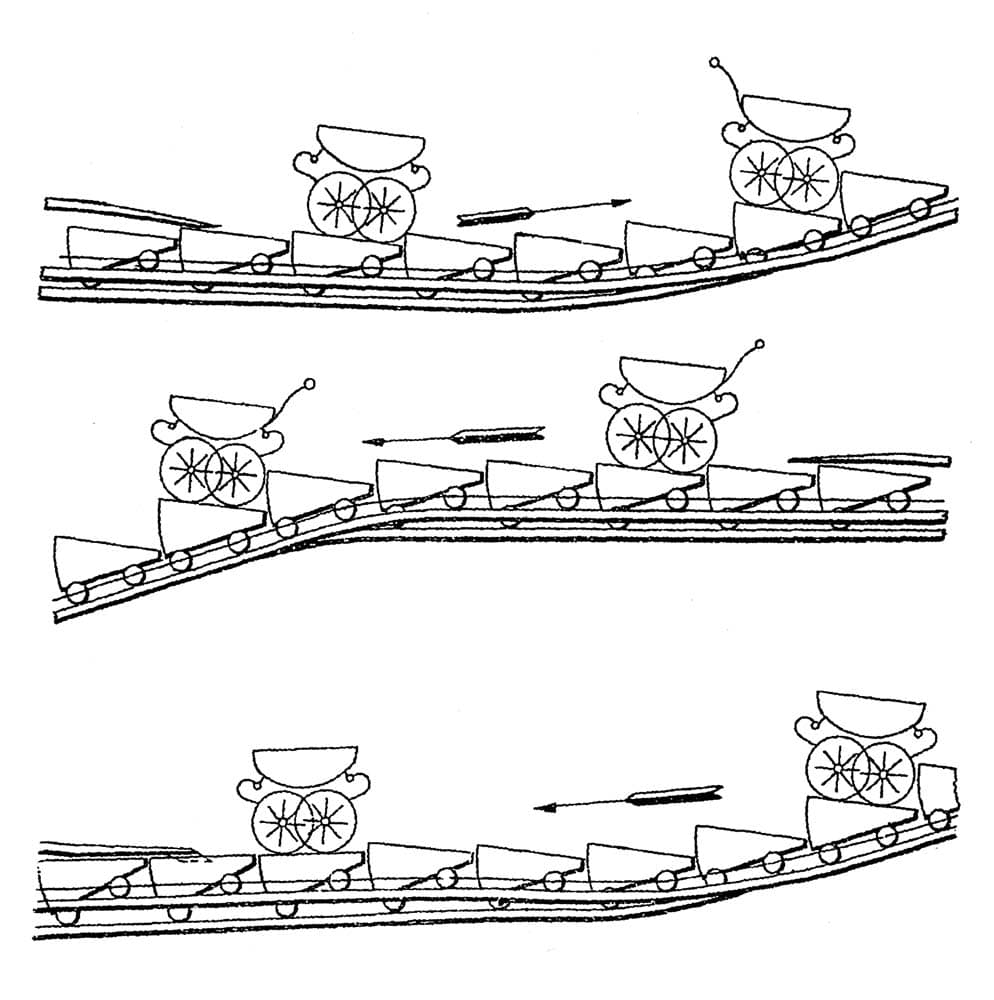

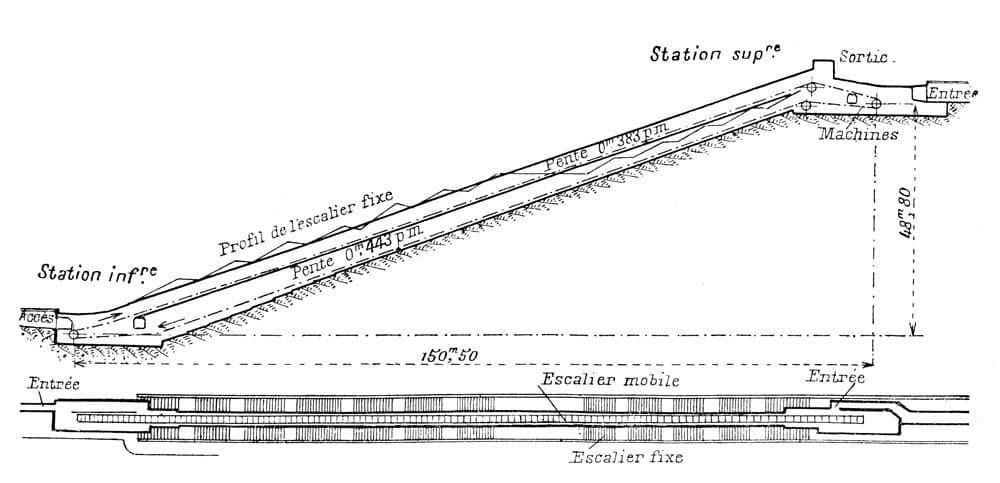

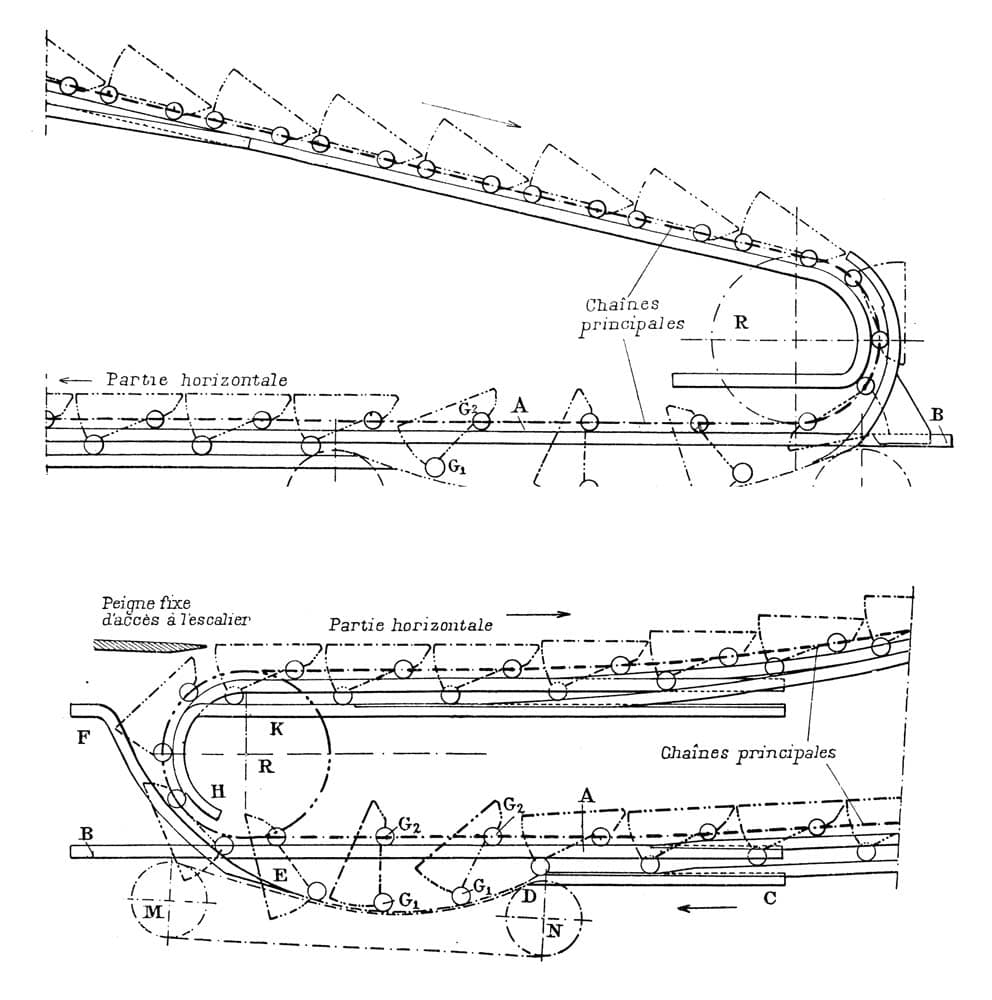

The patents were for a continuous escalator that consisted of ascending and descending stairs that were stacked on top of each other such that the upper stair carried ascending passengers and the lower stair (placed in a tunnel) carried descending passengers (Figure 1). The moving stairways employed a special track at each end that rotated the step frames, changing their orientation to serve their respective paths of travel. In order to provide an adequate vertical separation between the stacked flights, the entrances to the stairs were offset. The patent addendum addressed the need to facilitate “the transport of vehicles such as carts, bicycles, wheelbarrows, children’s carriages, etc.”[1] Hocquart proposed that each step tread have a slight downward tilt to help hold vehicle wheels in place, and he modified the landings to ease the transition onto and off the stairs (Figure 2). The combined patents presented a scheme that resembles countless other designs in its apparent oversimplification of a complex problem, and yet, perhaps surprisingly, the patents accurately reflected the essence of the escalator’s final design (Figure 3).

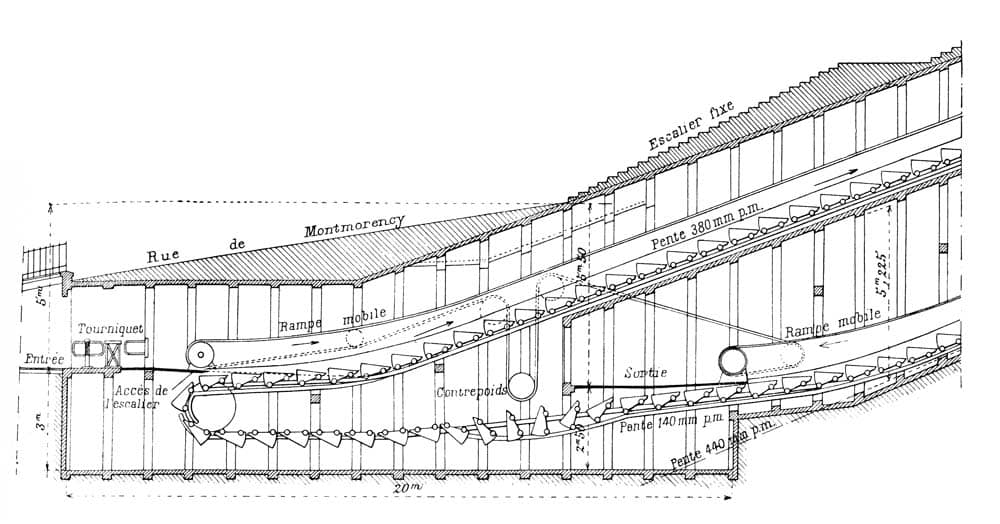

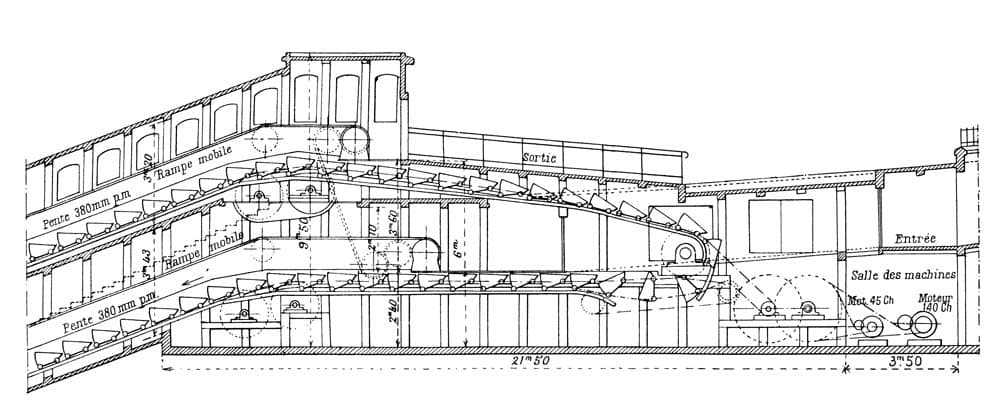

The site for the escalator was the Rue de Montmorency, the primary street linking the Frileuse Plateau and the Graville District. A stairway located in the median provided access for pedestrians. The stair was removed, and a trench was excavated along its length to serve as the site for the new escalator. However, unlike the scheme in Hocquart’s patent, where only the descending stair was located in a tunnel, the trench was intended to hold two tunnels or galleries such that the entire system was placed below grade and protected from the weather. Excavation began on February 2, 1926, and the galleries, built of reinforced concrete, were completed on October 10, 1927. The galleries included upper and lower passenger stations, an upper machine room and electrical substation, and inclined passages for the stairs. The project’s total length was 178 m, with the stair runs having a length of 125 m and a 38% slope (approximately 21°) (Figures 4 & 5).

The escalator had 356 steps with a tread depth of 0.96 m and a length of 1.6 m. The depth accommodated riders with carts, bicycles and children’s carriages, and each step was designed to carry 160 kg. The step treads were composed of hard wood slats that meshed with comb landings. The step frame rotating system was a simplified version of the design found in the patent (Figure 6). The completed system also featured a step-chain tensioning device at the lower end. This device was composed of a wheeled carriage whose action was controlled by counterweights that ensured the proper tensioning of the step-chain and allowed for movement (as needed). The stair also utilized an automatic lubrication system supplied by an oil tank that required filling twice per week.

The escalator’s power plant included two primary electric motors: a 45-hp motor capable of operating the stair at 0.40 m/s, and a 140-hp motor capable of operating the stair at 0.60 m/s (Figure 7). It also featured an auxiliary 10-hp motor that was attached via a belt to a flywheel on the 45-hp motor. This motor was intended for use during inspections and repairs, as it could move the escalator at a very slow speed. The motors were switched on and off from a control room located in the upper station. Emergency stop buttons were also located at the stair entrances and exits. Safety devices included an overspeed governor that activated a brake that slowed the escalator if it exceeded 10% of the maximum speed of 0.60 m/s; if the escalator exceeded 20% of the maximum speed, the governor stopped the stair.

Following completion, the system was subjected to a series of tests designed to ensure that it was safe for public use. The ascending and descending stairs were each subjected to separate loading tests. Because each step had a capacity of 160 kg, it was decided to load half the steps with 300 kg to simulate a full load. The report of the tests stated that, “To reduce handling to a minimum, the tests were carried out by loading the steps with empty barrels which were filled with water … When the trials were over, it was easy to get rid of the ballast.”[2] This account raises several questions: how many barrels were used per step, were the barrels centered on the stair treads and, perhaps most importantly, where did the water go when the barrels were emptied? The escalator reportedly easily passed these “very severe” tests.[2]

The escalator opened to the public on May 27, 1928 (Figures 8 & 9). During its first months of operation, the escalator was operated “almost exclusively” by the 45-hp engine, which provided a running speed of 0.40 m/s and a travel time of 5 min. This slow speed was intended to provide an adequate period of time for the public to become accustomed to riding before switching to the higher speed. During its first year of operation, the highest traffic hours were 11:30 a.m.-12:30 p.m., and 6-7:15 p.m. Between May 27, 1928, and March 15, 1929, the escalator operated for a total of 3,708 h and carried 830,921 ascending passengers, 360,327 descending passengers and 312,127 bicycles and carriages. The cost to ascend was 25 cents (carts, bicycles, etc., cost an additional 15 cents), while the cost to descend was only 15 cents (carts, bicycles, etc., cost an additional 10 cents).

The popularity of the system was such that it appeared on postcards, and accounts of the system appeared in numerous American newspapers in an article promoted by the Associated Press (Figure 10). The article’s lengthy title effectively summarized the essence, and the importance, of the Le Havre escalator: “French City Builds Large Escalator; Biggest Moving Stairway in the World Benefits Le Havre Workmen; Opens New District; Wooded Hillside Formerly Difficult to Reach Now Popular for Homes.”[3] The escalator remained in continuous operation until 1964, when it was closed for a brief period. It resumed operation in 1965, and was permanently removed from service in 1984. The escalator was not, however, removed. Regrettably, the expense of revitalizing the system has, thus far, meant that it remains an elegant ruin and a reminder of the power of the escalator to serve, not only buildings, but entire communities.

References

[1] Escalier mécanique élévateur er descendeur, 1re Addition Au Brevet D’Invention No. 589.503 & No. 30.227, Edouard Louis Hocquart & Société Anonyme des Anciens Établissements Grosselin Père et Fils, Paris (August 26, 1926)

[2] Thooris, L’Escalier Roulant de la rue de Montmorency au Havre, Le Génie Civil, (March 30m,1929)

[3] “French City Builds Large Escalator,” Baltimore Sun (September 9, 1928)

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.