The Salem Elevator Works (Part One)

Oct 6, 2022

A glimpse into a unique aspect of VT history

The history of the vertical-transportation (VT) industry in the U.S. includes numerous regional companies that provided machines that met the needs of the country’s factories. These machines, which primarily carried freight in place of passengers, played a critical role in the development of America’s industrial infrastructure. Although the story of the development of the passenger elevator has dominated VT history, the history of freight elevators embraces the same critical components of invention, manufacturing and marketing. The story of the Salem Elevator Works (established as the Salem Foundry and Machine Shop) provides a glimpse into this important aspect of VT history.

The Salem Foundry and Machine Shop was founded in March 1870 in Salem, Massachusetts. One of the company’s first advertisements, which appeared that same year, listed the products and services offered by the new firm:

“Castings, heavy and light, made in the best manner and warranted. All kinds of machine and mill works made to order. Steam engines built and repaired. All kinds of steam and water pipe of any size. A superior jack screw for raising buildings, constantly on hand at low prices. All kinds of jobbing in our line.”[1]

Noticeably absent from this list is any mention of hoists or elevators. Following the marketing strategy employed by other foundries and machine shops, the advertisement’s implied message was that the company could build anything a customer needed. From 1870 to 1880, this advertising strategy remained in place, with no overt references made to the manufacture of VT systems. However, during this decade a figure appeared on the scene who changed the company’s trajectory.

One of the earliest mentions of Charles F. Curwen (1853-1909) appeared in the 1872 Salem Directory, which listed his occupation (at age 19) as that of clerk in the Naumkeag Mills. Four years later the Directory reported that he was employed by Salem Foundry and Machine Shop as a bookkeeper. However, the following year he abandoned his “desk job,” and he listed his new occupation as “iron founder and machinist.” This is all of the biographical information other than the fact that he was “educated in the public schools” that is known about Curwen.[2] This lack of information compounds the mystery found in a line of text that appeared immediately below the company’s name in an 1879 advertisement: “Charles F. Curwen, proprietor.”[3] How and with what resources Curwen became the proprietor, and thus presumably the owner, of the company is unknown. What is known is the impact of his leadership on its future.

An announcement of the company’s products, published in the September 1881 issue of The Manufacturer and Builder, revealed an important addition to its product line:

“Among the many manufactures of the Salem Foundry and Machine Shop, at Salem, Mass., may be mentioned as most prominent, elevators, shaping machines, lathes, tan presses, shafting, hangers and pulleys, and grate bars for steam boilers. This concern also does all kinds of machine jobbing, and guarantees the best skill and workmanship.”[4]

The fact that “elevators” was the first “prominent” item mentioned is of interest because this was also the first public reference to the company’s ability to manufacture elevators. Interestingly, no subsequent references to elevators appeared in the company’s advertisements for the next three years. This surprising lag in promoting their new product line did not, however, indicate a lack of activity by Curwen.

In August 1883, he partnered with Alfred H. Hall of Boston to establish the Hall Elevator Safety Attachment Co., with Hall as president and Curwen as treasurer.[5] In 1880, Hall had patented a safety device designed to prevent a car from falling if the hoisting rope broke: Safety Appliance for Elevators, U.S. Patent No. 230,006 (July 13, 1880). As was the case with many inventors, he first outlined the current state-of-the-art:

“(Although) various devices have been invented for this purpose, most of them relate to levers or cams which are attached to the car and are arranged to engage with racks upon the walls of the elevator-well upon the breaking of the hoisting-rope, and in actual practice many of these methods have proved to be impracticable.”[6]

Hall’s solution to the “impracticable” rack-and-pinion device was a simple wedge-shaped block that stopped the car’s downward movement in the event of a rope failure:

“The wedge-block may be raised and lowered by the same drum that is used in winding and unwinding the car hoisting rope, or it may be operated in any other desirable way, the essential feature of this part of the invention being the wedge-shaped block, not connected with the car or its hoisting-rope, arranged to travel with the car, immediately below it, in such a position that upon the breaking of the hoisting-rope the car shall descend thereon with as little momentum as possible, and become wedged between the walls of the elevator-well.”[6]

The presentation of the safety in patent’s text and illustrations appears to place the device in the realm of numerous other questionable inventions that were proposed but never manufactured (Figure 1). This was not, however, the case with Hall’s safety. It was first employed on the Salem Foundry and Machine Shop’s elevators in 1883 and remained in use throughout the opening decade of the next century. In fact, it is possible that Curwen may have been the Hall Elevator Safety Attachment Co.’s only client (the company was dissolved in 1892).

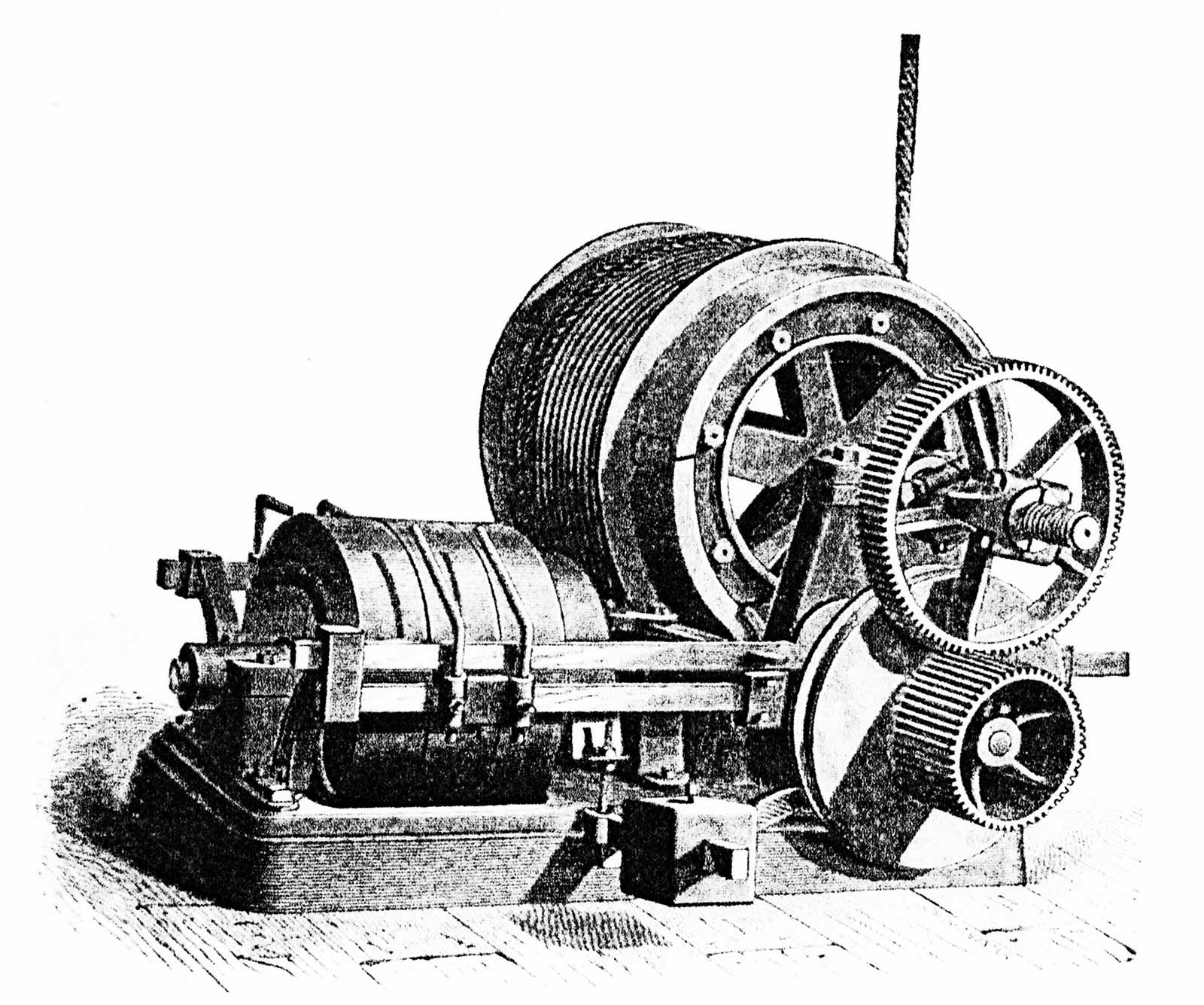

The first advertisement that mentioned elevators appeared in 1884. It indirectly referenced Curwen’s association with Hall in a statement noting that the company manufactured elevators equipped with a “patent safety attachment.”[7] The advertisement also featured an engraving of a belt-driven drum hoisting engine (Figure 2). During this period, Curwen’s marketing skills were also evident in his use of promotional materials, as was reported by Mechanics magazine:

“Mr. Charles F. Curwen, of the Salem Foundry and Machine Shop, Salem, Mass., sends us a very neat 1884 calendar. The design is a pretty one, engraved by John A. Lowell & Co., and bears the inscription, ‘Our compliments and wishes for a prosperous year.’ Between the leaves containing the months of the year are brief references to the various goods manufactured by the concern.”[8]

Unfortunately, a copy of the calendar has not survived, thus it is unknown what references to elevators may have been included. This marked the beginning of Curwen’s use of promotional materials and press releases that were regularly provided to a variety of industry and engineering publications in order to market his elevators.

One of the next examples of this strategy appeared in a leading trade journal for an industry that was to play a significant role in the company’s success. The May 4, 1889, issue of Wade’s Fiber and Fabric: A Record of New Industries in the Cotton and Woolen Trades included the following announcement:

“Another prominent firm manufacturing textile machinery whose advertisement appears in ‘Wade’s Fiber and Fabric,’ is the Salem Foundry and Machine Shop of Salem, Mass. Their specialty is elevators of superior construction, which are now in some of the best mills in the country. The Salmon Falls Manufacturing Co., (N.H.), and the Stark Mills at Manchester, N.H., have recently ordered elevators from this company both orders being for the patent automatic hatch attachment.”[9]

As is indicated in its title, Wade’s Fiber and Fabric was dedicated to the interests of the textile industry. In this context it is intriguing that they chose to characterize Curwen’s company as a “prominent firm manufacturing textile machinery,” a statement that clearly implied that his elevators were somehow uniquely suited for use in textile mills. No evidence has been found that suggests that these elevators employed any special features that distinguished them from machines made by their competitors. This was, however, one of the first indications of a marketing strategy through which Curwen sought to establish his company as the primary supplier of freight elevators by this industry.

This brief announcement also referenced the fact that his elevators now featured a “patent automatic hatch attachment.” Unfortunately, the nature of this device and its associated patent have not been found. This device may have been related to automatic hatch-cover systems. The majority of freight elevators employed in industrial settings operated in open wooden framework shafts, and they employed hatch covers to prevent workers from falling into the shaft when the car was absent. This supposition is supported by a later article that described these machines. A press release published in December 1889 included information on the elevators’ standard design features:

The Salem Foundry and Machine Shop, Salem, Mass., manufacturers of elevators, report business to be very satisfactory, their sales this year being larger than any previous year. Among recent sales may be noted the following: Tremont and Suffolk Mills, Lowell, Mass., Locke Bros., Salem, Mass., Great Falls Mfg. Company, Great Falls, N.H., and Wamsutta Mills, New Bedford, Mass. They make a specialty of safety appliances for elevators, including automatic hatches, both sliding and folding, and the Weld Automatic-Lock Gate, which is self-closing and is always locked, excepting when the car is at the landing.[10]

The company’s ability to provide automatic sliding and folding hatch systems may have derived, at least in part, from the patent referenced in the 1885 article. It is also of interest that Curwen claimed that his company specialized in the production of “safety appliances for elevators,” which now included the Weld Automatic-Lock Gate.

The gate system was designed by George A. Weld of Winchester, Massachusetts, and was the subject of two patents: Elevator, U.S. Patent No. 355,427 (January 4, 1887) and Elevator, U.S. Patent No. 388,469 (August 28, 1888). It was also the subject of a promotional pamphlet developed by Curwen in January 1890, which was sent to various technical journals, including The Iron Age:

“From the Salem Foundry and Machine Shop, Salem, Mass., we have received a small pamphlet describing and illustrating their automatic lock elevator well gate. It is claimed that the use of this device will prevent falling through elevator openings, for the simple reason that the gate is always locked except when the elevator car is at the landing.”[11]

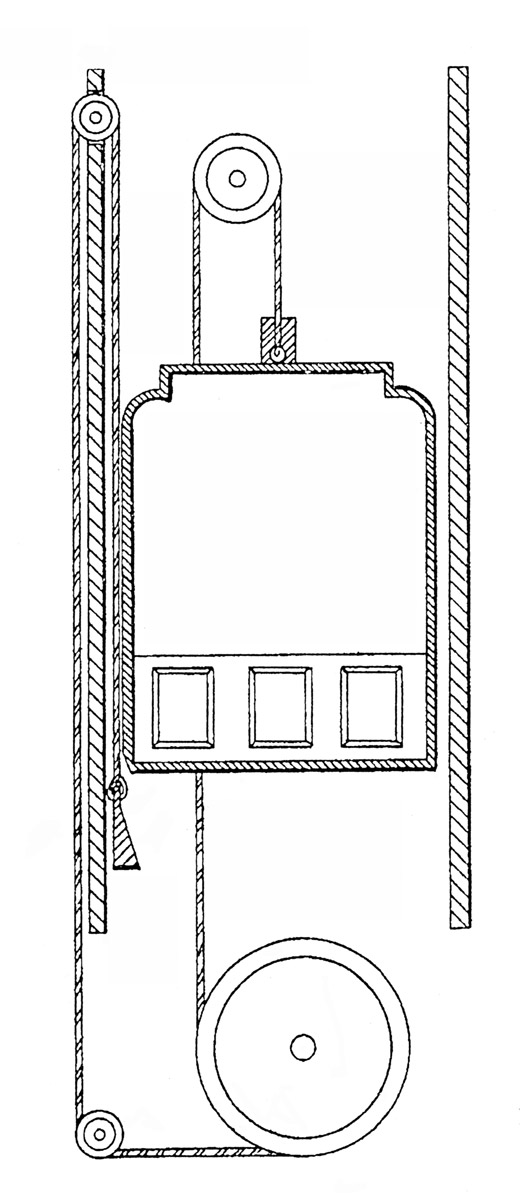

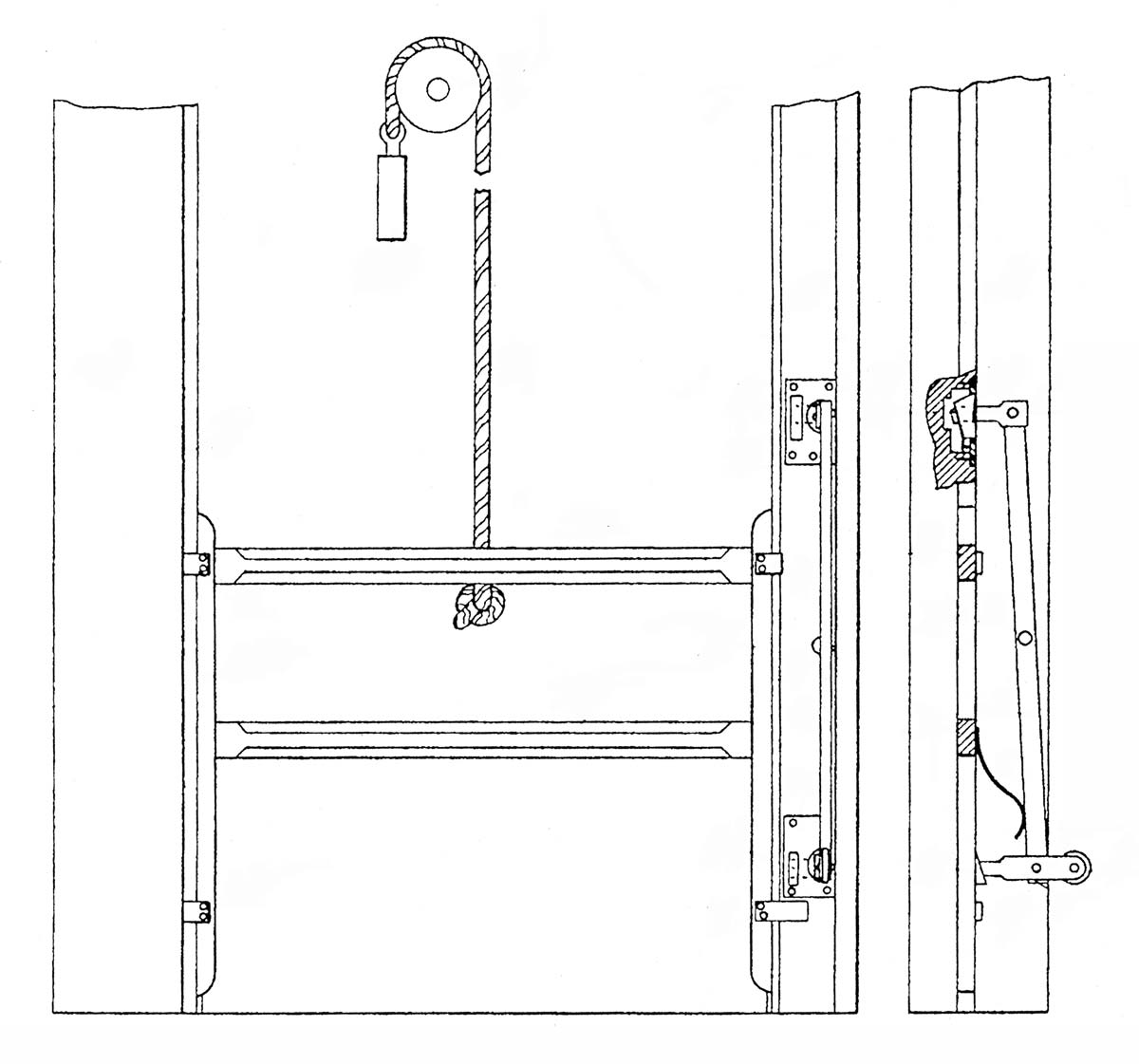

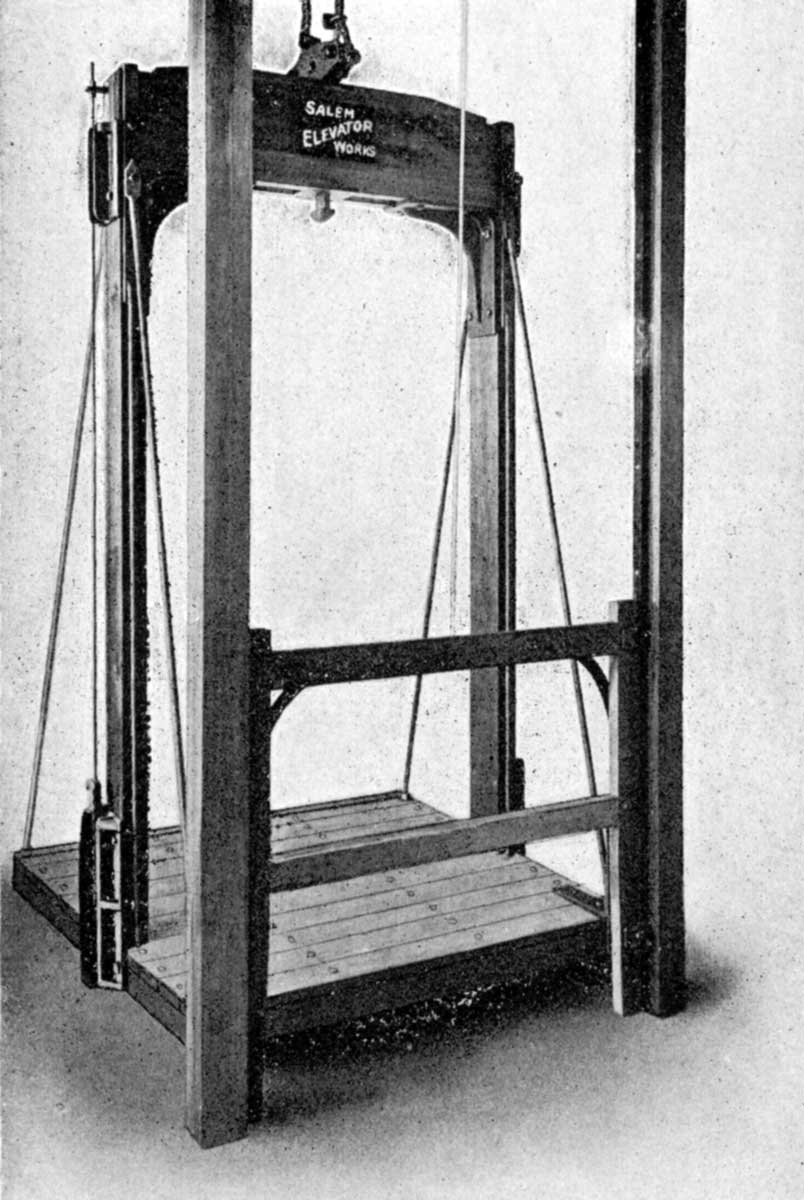

As was the case with the 1884 calendar, a copy of the pamphlet has not survived. Weld’s patent drawings give an indication of the gate’s design, which featured two horizontal bars that provided minimal shaft protection (Figure 3). In spite of offering only limited safety (from a modern viewpoint), this simple gate remained a standard feature of Curwen’s elevators into the next century (when its description was revised to a semi-automatic gate) (Figure 4). It was also marketed as a stand-alone product that could be added to existing elevators:

“The Salem Foundry and Machine Shop, Salem, Mass., manufactures of freight elevators, are meeting with great success with their automatic locking gates for elevator openings. Among their recent sales may be noted the following: Pacific Mills, Lawrence, 29; Everett Mills, Lawrence, 5; Springfield Prov. Co, Springfield, 15; Lyman Mills, Holyoke, 3; Overman Wheel Co., Chicopee Falls, 3; Spartan Mills, Spartanburg, S.C., 8; Lynchburg Cotton Mills, Lynchburg, Va., 4; Sewall & Day Cordage Co., Boston, 9; Chelsea Jute Mills, Brooklyn, N.Y., 10; Salem Building Association, Salem, 8, and many others.”[12]

This success, coupled with steadily increasing sales of freight elevators – primarily to textile mills — allowed Curwen to report in August 1890 that business was “uncommonly good for this time of year.”[13]

The conclusion of this story will address Curwen’s continued success in establishing his company as the leading supplier of freight elevators to the textile industry, the gradual expansion of his product line, and the transformation of the Salem Foundry and Machine Shop into the Salem Elevator Works.

References

[1] History and Directory of Essex County (1870).

[2] Obituary, Boston Evening Transcript (December 30, 1909).

[3] The Salem Directory, Boston: Samson, Davenport, & Co. (1879).

[4] “Miscellaneous and Advertising,” The Manufacturer and Builder (September 1881).

[5] “New Corporations,” Boston Globe (August 29, 1883).

[6] Alfred H. Hall, Safety Appliance for Elevators, U.S. Patent No. 230,006 (July 13, 1880).

[7] Essex County Directory for 1884-1885, Boston: Briggs & co., Publishers (1884).

[8] Untitled, Mechanics (March 8, 1884).

[9] Untitled, Wade’s Fiber and Fabric (May 4, 1889).

[10] “Special Mention,” Building (December 28, 1889).

[11] Untitled, The Iron Age (January 30, 1890).

[12] “Special Mention,” Architecture and Building (August 23, 1890).

[13] “Special Mention,” Architecture and Building (August 2, 1890).

Also read: The Salem Elevator Works (Part Two)

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.