1923 William Wadsworth & Sons Estimate & Specification

Dec 3, 2024

Comparing this with the Specification and Tender from the last issue

The previous issue of ELEVATOR WORLD UK featured an investigation of a 1927 Specification and Tender for an electric goods lift prepared by Smith, Major and Stevens, Ltd. for Atlas Works (Shrewsbury), which provided insights into the company’s business practices. This investigation prompted an important question: Was this document representative of an industry standard of practice? The recent discovery of a 1923 Estimate and Specification prepared by William Wadsworth & Sons, Ltd. for the Crewe Co-operative Friendly Society, Ltd., based in Crewe, allows for a comparison that will help answer this question.[1]

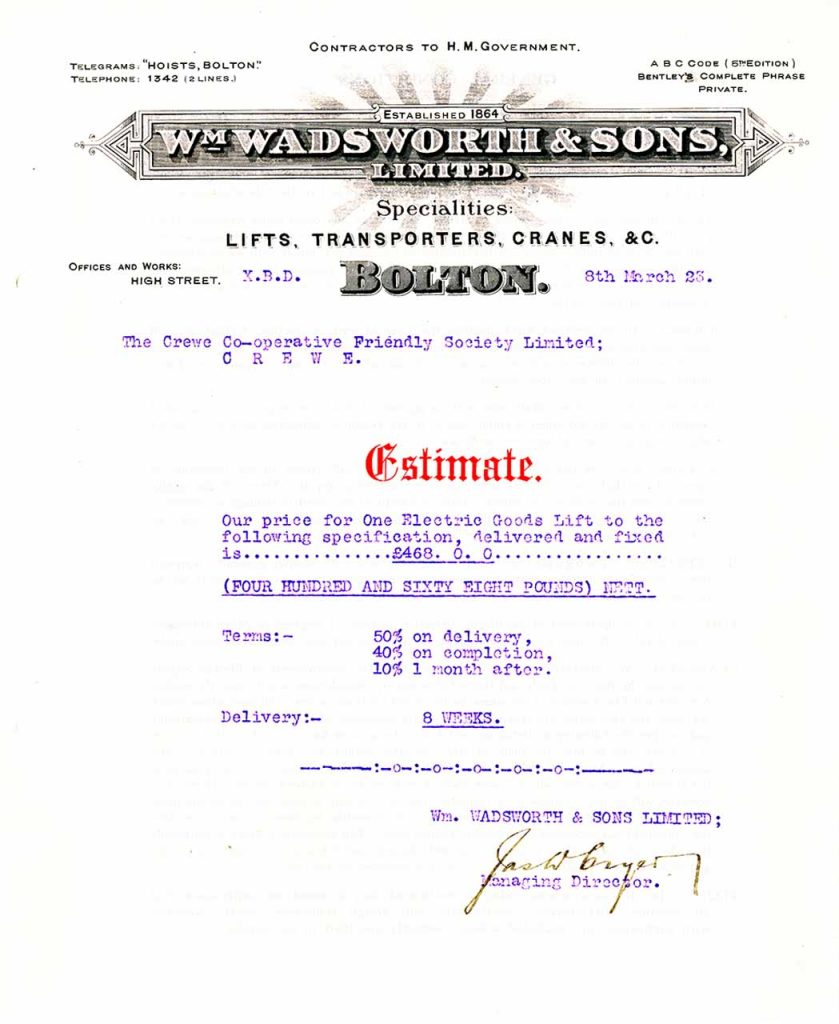

Like Smith, Major and Stevens, Wadsworth was an established firm. Founded in 1864, the company was a well-known builder of lifts, transporters and cranes. Their Estimate and Specification followed a format similar to Smith, Major and Stevens’ slightly later example. The relevant materials, which included a letter from Wadsworth to the Co-operative, a cost estimate, the specification and a list titled A Few Users of the “Wadsworth” Electric Lift, were presented in a “branded” folder. However, whereas Smith, Major and Stevens featured their company name on their folder, Wadsworth simply proclaimed that they were providing information on The Wadsworth Lift (Figure 1). This designation may have been intended to imply that their lifts were distinctive and, presumably, “better” than those made by their competitors.

Wadsworth’s letter to the Co-operative, dated 8 March 1923, reveals that the company received the Co-operative’s inquiry on Friday, 2 March. In the six days between receipt and response, Wadsworth arranged a visit to Crewe by one of their engineers in order to assess the site and situation. The letter also reveals that the Co-operative was seeking to replace an existing steam-powered lift with a new electric goods lift. The presence of a working steam-powered lift in the early 1920s raises a question about the nature of the U.K. vertical-transportation (VT) landscape during the early 20th century: What was the technological character and make-up of the U.K. lift inventory in 1923 with regard to “old” versus “new” systems?

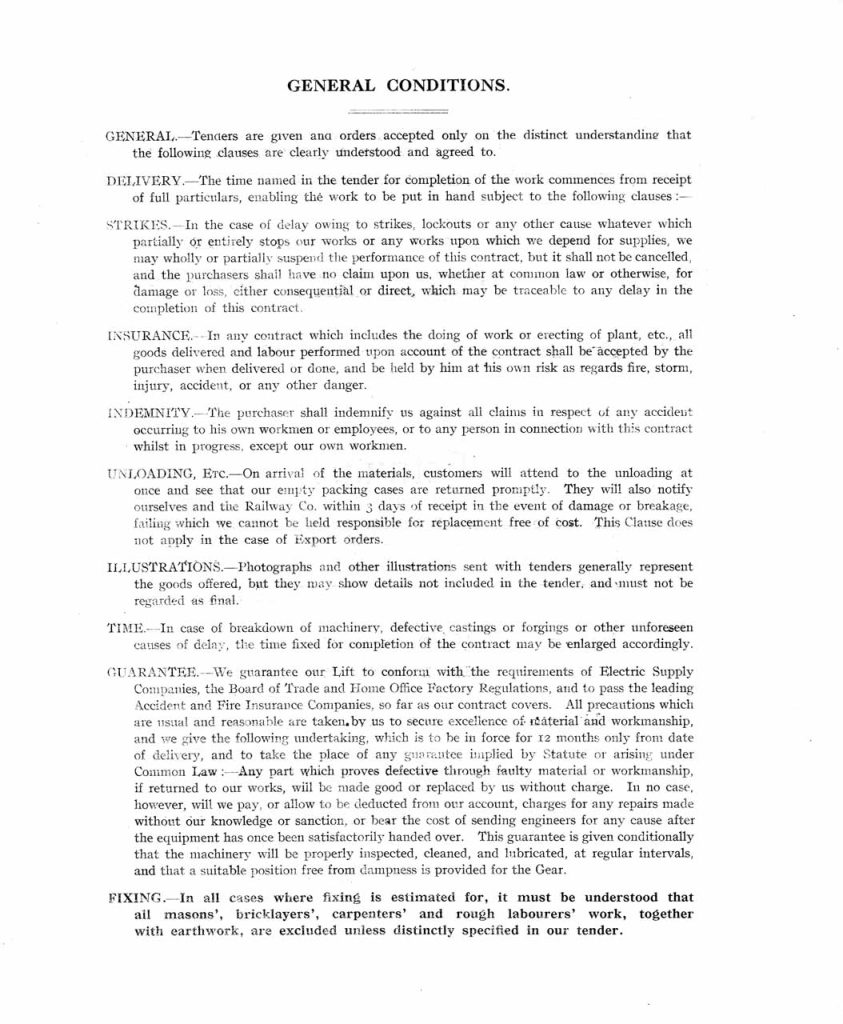

The official estimate was presented on the only two-sided page included in Wadsworth’s folder. The preprinted page featured the estimate on one side (with relevant details typed into the allotted spaces), with the General Conditions of service printed on the back (Figures 2 and 3). The estimate summarized the project cost as follows: “Our price for one electric goods lift to the following specification, delivered and fixed is £468.” In comparison, the Smith, Major and Stevens’ estimate featured a more detailed breakdown of individual component costs. Wadsworth’s terms of payment were defined as “50% on delivery, 40% on completion and the final 10% one month after.” Upon acceptance of the estimate, the expected “delivery time” of the completed lift was eight weeks. The General Conditions included definitions of and information on delivery, strikes, insurance, indemnity, unloading, illustrations, time, guarantee and fixing.

The conditions also clearly defined the responsibilities of the “purchaser” and Wadsworth. With regard to insurance and indemnity, the burdens fell solely on the purchaser:

“In any contract which includes the doing of work or erecting of plant, etc., all goods delivered and labour performed upon account of the contract shall be accepted by the purchaser when delivered or done, and be held by him at his own risk as regards fire, storm, injury, accident or any other danger. The purchaser shall indemnify us against all claims in respect of any accident occurring to his own workmen or employees, or to any person in connection with this contract whilst in progress, except our own workmen.”

The issue of the purchaser accepting “deliveries” was further addressed in the section titled Unloading:

“On arrival of the materials, customers will attend to the unloading at once and see that our empty packing cases are returned promptly. They will also notify ourselves and the Railway Co. within three days of receipt in the event of damage or breakage, failing which we cannot be held responsible for replacement free of cost.”

Wadsworth apparently utilized specialized – and reusable – “packing cases” to ensure that their equipment arrived safely on-site. Additionally, they apparently relied on the purchaser – unsupervised by a Wadsworth employee – to safely unload and store the lift components upon arrival.

The section on strikes was similar to that found in Smith, Major and Stevens’ tender:

“In the case of delay owing to strikes, lockouts or any other cause whatever which partially or entirely stops our works or any works upon which we depend for supplies, we may wholly or partially suspend the performance of this contract, but it shall not be cancelled, and the purchasers shall have no claim upon us, whether at common law or otherwise, for damage or loss, either consequential or direct, which may be traceable to any delay in the completion of this contract.”

Wadsworth also offered, as did Smith, Major and Stevens, a “guarantee” on their completed work:

“We guarantee our Lift to conform with the requirements of Electric Supply Cos., the Board of Trade and Home Office Factory Regulations and to pass the leading Accident and Fire Insurance Companies, so far as our contract covers. All precautions which are usual and reasonable are taken by us to secure excellence of material and workmanship, and we give the following undertaking, which is to be in force for 12 months only from date of delivery, and to take the place of any guarantee implied by Statute or arising under Common Law: Any part which proves defective through faulty material or workmanship, if returned to our works, will be made good or replaced by us without charge. In no case, however, will we pay, or allow to be deducted from our account, charges for any repairs made without our knowledge or sanction, or bear the cost of sending engineers for any cause after the equipment has once been satisfactorily handed over. This guarantee is given conditionally that the machinery will be properly inspected, cleaned and lubricated, at regular intervals, and that a suitable position free from dampness is provided for the gear.”

The guarantee offers a glimpse into the limited regulatory world of the 1920s. It also suggests, in linking the guarantee to regularly scheduled inspections, cleaning and lubrication, that Wadsworth may have offered these services – likely for an annual fee – to their customers. The requirement that the lift machinery be placed in a location “free from dampness” is likely a condition that would have been assessed prior to the lift’s installation.

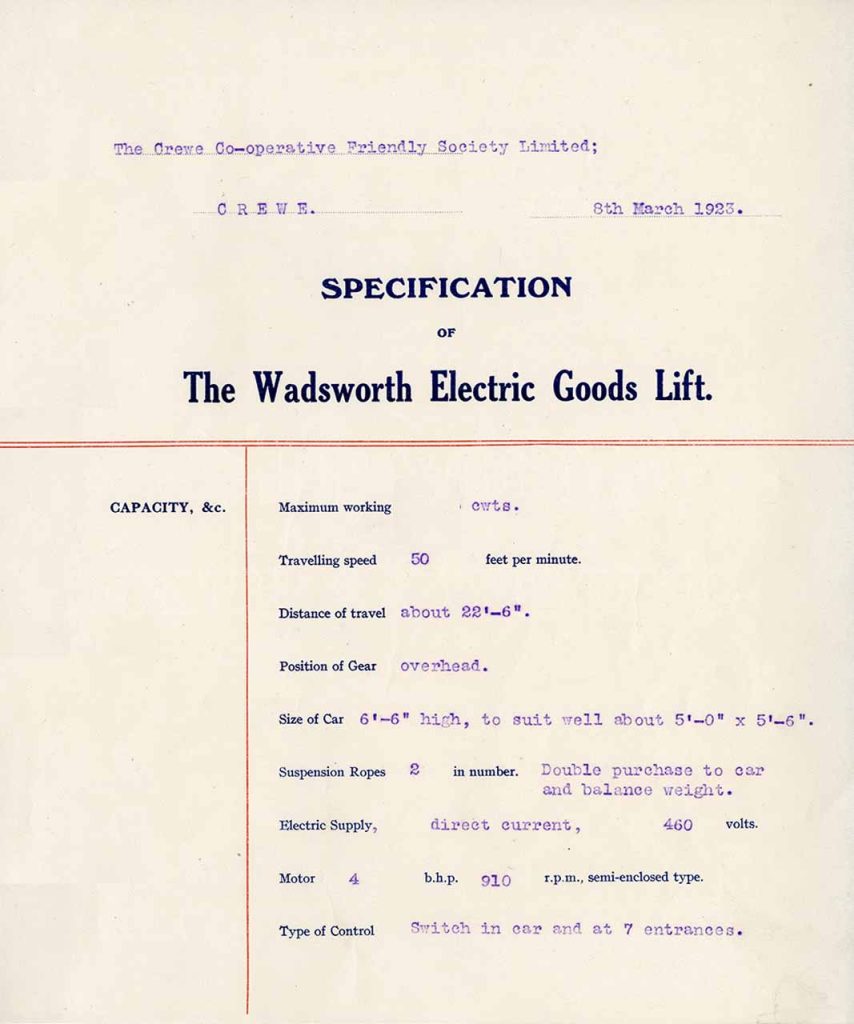

The specification was a six-page, pre-printed document that was designed to allow additional details to be added via typewriter (Figure 4). Its title, Specification of the Wadsworth Electric Goods Lift, implies that Wadsworth had similar documents designed for use with their electric passenger lifts and their hydraulic lifts. The specification included sections titled capacity, winding machine, rope sheaves, electric motor, brake, direction switches, main limit switch, controller, car switch, automatic push control, car, safety gear, runners, suspension ropes, balance weights, erection and excluded work. Unlike Smith, Major and Stevens’ specification, which included images of the various lift components, Wadsworth’s specification was unillustrated. The lift’s “capacity” was defined in terms of its maximum working load, travelling speed, distance of travel, position of gear, size of car, suspension ropes, electric supply, motor and type of control. The lift’s maximum load was 15 cwts. (1830 lbs or 830 kgs), and its maximum speed was 50 ft/min (15.24 m/min). The electric motor was described as having been “specially built for lift duty,” and Wadsworth assured its clients that their motor “ran smoothly and sparklessly under varying loads up to the maximum capacity in either direction.” The electro-mechanical brake was fitted with “swivel cast-iron shoes lined with Ferodo fibre” (Ferodo, founded in 1894, was one the first companies to produce asbestos brake pads and linings).

The lift, which had a vertical run of 22.5 ft (6.9 m), served seven landings. The estimated net cost of £468 was predicated on providing the means to control the lift from within the car and at each landing. The controller was described as being:

“of substantial electrical and mechanical construction, and consists of the necessary switch gear for starting, stopping and reversing the motor. It is arranged to give a perfectly accelerated start and stoppage free from jerk, and so interlocked that it is impossible to operate both directions at the same time, or reverse quickly without the armature starting resistance being first re-inserted (which is done automatically).”

The car switch featured “a spring to bring it to the ‘off’ position when released and (was) fitted with a detachable handle which can only be inserted or removed when the switch is in the ‘off’ position.” The precise need for a detachable switch handle is unknown. It may have been an added safety feature that ensured that the lift could only be operated by trained personnel. The nature of the landing lift controls is unknown.

The lift operating system was also the only aspect of Wadsworth’s proposal where they offered the Crewe a choice between two options:

“You will notice that we have given alternative prices for the lift controlled at seven points as well as from inside the car, and for control from inside the cage only. If you decide on the former it will be essential to fit the three openings of the car with safety gates, for which we have included, but if you have the lift operated from inside the car only, these three gates can be dispensed with. For the purpose of effecting the highest degree of safety, however, we would not recommend you to do this.”

If the lift was to be operated “from the car only, and car fitted with a buzzer-indicator, thus dispensing with the seven outside control switches,” the cost was reduced to £440. The fact that an “unsafe” option was offered by Wadsworth – the possible elimination of the car gates – speaks to the lack of regulation during this period.

Wadsworth did provide a push-button system of control (referred to in the specification as automatic push control):

“With this system, the lift is controlled by a set of pushes in the car corresponding to the number of floors served, and one push on each landing to call the lift. Momentary pressure only is required. An emergency push is also provided in the car to stop the lift at any point should this be necessary.”

It’s of interest that this system was not offered as an option for a goods lift. Of equal interest is the lack of any reference to an automatic levelling system.

Wadsworth, as did Smith, Major and Stevens, specified that they only provided labour associated with the actual lift installation:

“When our estimate includes erection, it is to be distinctly understood that we provide skilled fitters only, and that purchasers are to provide at their own expense such rough labouring assistance as may be necessary, together with scaffolding. We do all wiring-up in conduit between the motor, controller, limit switches, etc.; purchasers to bring their electric supply to within 6 ft of the gear, and terminate at a set of switches and fuses.”

The presence of a working steam-powered lift in the early 1920s raises a question about the nature of the U.K. VT landscape during the early 20th century: What was the technological character and make-up of the U.K. lift inventory in 1923 with regard to “old” versus “new” systems?

They also explicitly stated that their offer excluded:

“Any cutting away and making good.

Wood bricks or other guide attachments.

Trimming of floors (if required).

Preparation of pit at bottom of well-hole.

Any building work to receive the lift and gear.

R. S. joists to carry the gear.

Enclosure of well-hole and gear.”

Additionally, the purchaser was required to remove any “existing gear and guides.” Wadsworth’s installation specifications (and exclusions) were similar to those found in Smith, Major and Stevens specification.

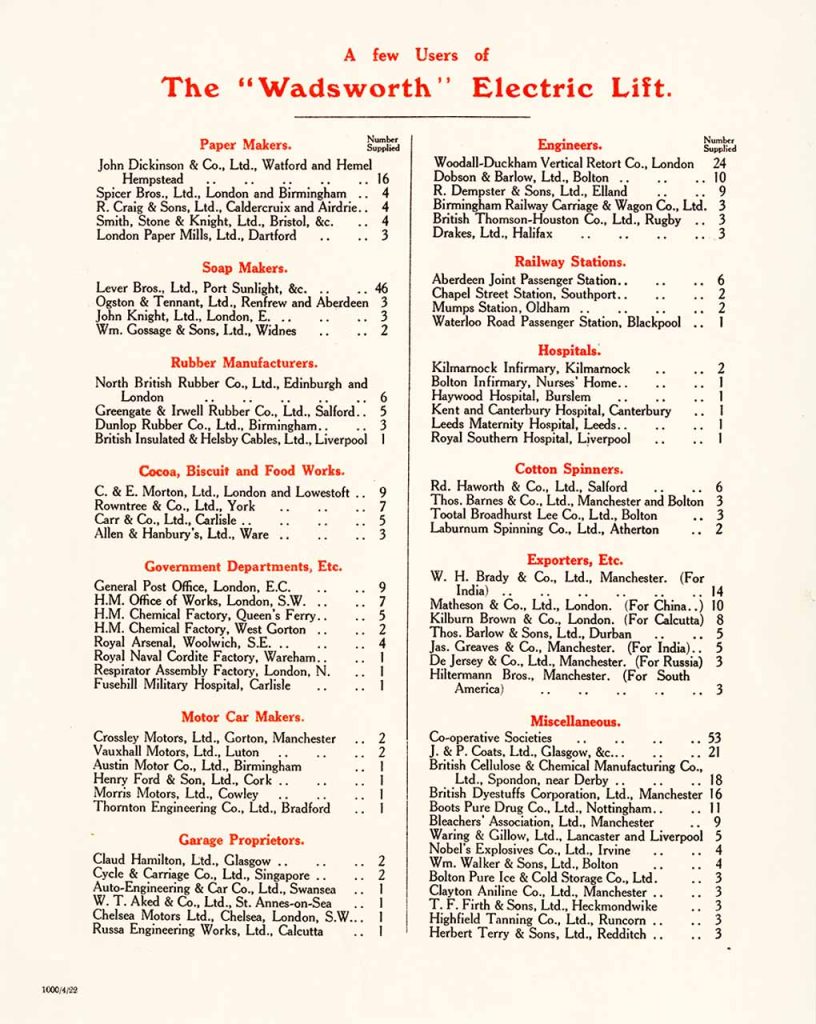

The final page in the Wadsworth folder was titled A Few Users of the “Wadsworth” Electric Lift. Smith, Major and Stevens included a similar sheet in their folder, with their lifts presented in five general categories: government installations, office buildings, industrial buildings, ocean liners and overseas installations. Wadsworth divided their electric lift users into 13 distinct categories: paper makers; soap makers; rubber manufacturers; cocoa, biscuit and food works; government departments, etc.; motor car makers; garage proprietors; engineers; railway stations; hospitals; cotton spinners; exporters, etc.; and miscellaneous (Figure 5). This more precise division of users may have been represented an effort to illustrate the diversity of their electric goods and passenger lifts.

The similarities in organization and content between Wadsworth’s 1923 Estimate and Specification and Smith, Major and Stevens’ 1927 Specification and Tender clearly reveal that, by the 1920s, the U.K. VT industry had established a consistent business practice with regard to presenting lift proposals to prospective clients. These two proposals also provide insights into typical installation practices during this period. Future articles will continue to explore the history of U.K. VT industry practices.

Reference

[1] Estimate and Specification, William Wadsworth & Sons, Ltd. (1923). All quotations derive from this document.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.