Hallé’s Moving Way for Transporting Persons and Goods

Aug 1, 2015

French engineer Jacques Hallé and his invention that established him as a father of the modern escalator

The origins of the modern escalator are often discussed solely in terms of the contributions of three American inventors: Jesse Wilford Reno (ELEVATOR WORLD, December 2003), George A. Wheeler (EW, July 2008) and Charles D. Seeberger (EW, April 2008). However, European inventors played an equally important role in the initial development of this new transportation system, and they were, occasionally, ahead of their American counterparts. In 1897, French engineer Jacques Hallé (1864-1945) designed a system that resembled Reno’s inclined elevator in its basic operation, and in May or June of that year, he successfully installed a machine in the Grands Magasins du Louvre, one of Paris’ leading department stores. Reno’s first interior installation, in Bloomingdale’s Department Store in New York City, was not completed until June 1898. Thus, the first interior commercial use of this new system occurred in Europe, and the extensive (and international) press coverage the installation received established Hallé as a key figure in this emerging field.

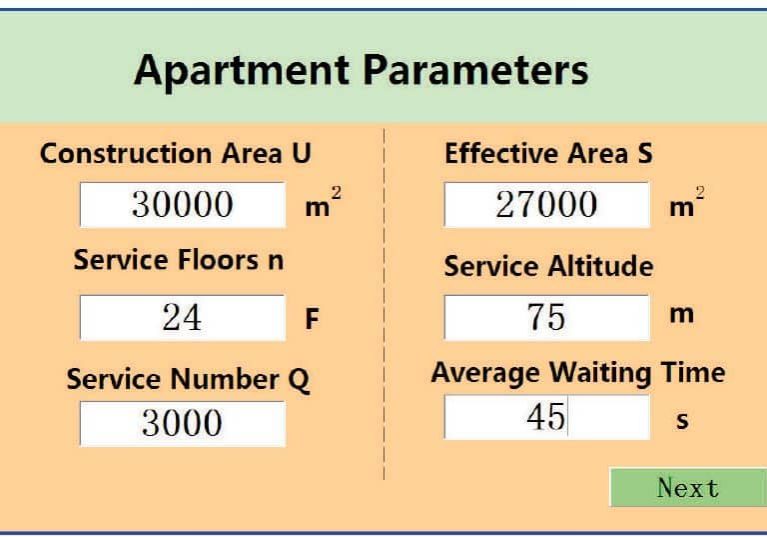

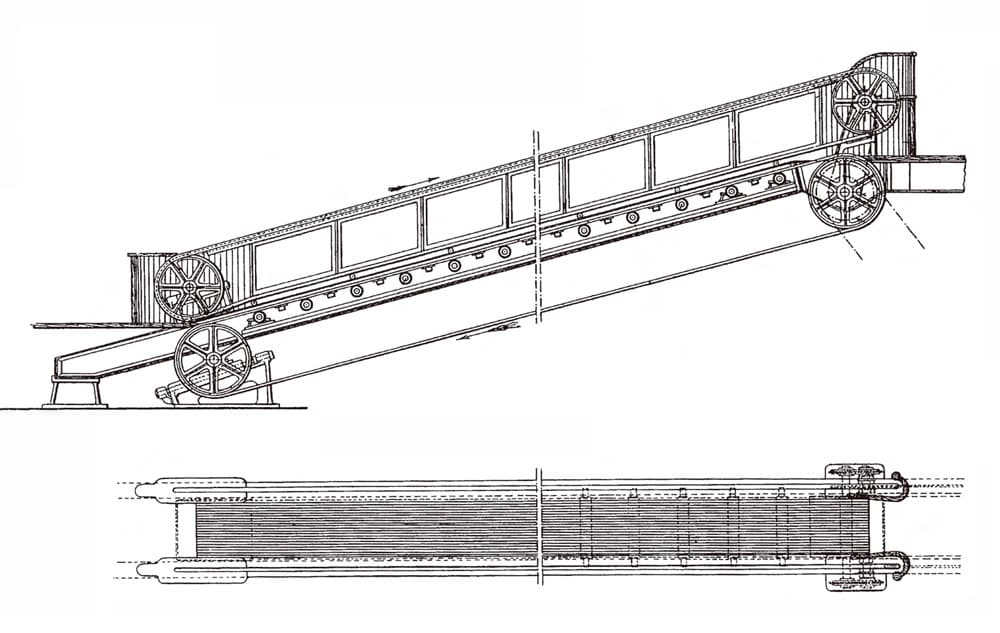

Hallé had received the French patent for his system several months prior to the Grands Magasins du Louvre installation: “Nouveau Dispositif de Chemin Mobile pour Èlever ou Transporter des Personnes ou les Marchandises,” French Patent No. 265,663 (April 5, 1897). In August and November 1897, he filed patent applications in both the U.K. and U.S. The former was awarded in late 1897: “Improvements in Moving Ways for Transporting Persons and Goods,” British Patent No. 19,803 (December 4, 1897), and the latter was awarded in 1898: “Moving Way or Stair for Transporting Persons and Goods,” U.S. Patent No. 602,008 (April 5, 1898). His design employed a flexible “moving way” that consisted of “a smooth and continuous surface. . . capable of being readily stretched.”[1] The thick belt or apron upon which passengers traveled was made of “thin strips of leather placed on edge side by side one behind another, so as to avoid break joints, and sewed together” (Figure 1).[1] Hallé proposed to use an electric motor to power his system, and he employed a system of moving handrails (one per side). He also explored the possibility of his machine serving more than one floor. He designed a system whereby the flexible belt passed under the floor such that, while it would be continuous throughout several stories, the passenger would experience the moving ways as individual units (Figure 2).

In their description of the Grands Magasins du Louvre installation, the French engineering periodical L’Eclairage Electrique referred to Hallé’s machine simply as a plan incliné, or inclined plane. The machine carried passengers between the first and second floor, was approximately 1 m wide, operated at a speed of 30 cm per second (.67 mph) and was powered by a 15-hp electric motor. The description of its operation appears to indicate that it operated in one direction: upward. The experience was described as smooth and without “jolts,” with riders gently deposited on the upper floor and exiting effortlessly in a “natural” manner by stepping off of the apron.[2] This graceful exit was possible because the upper end of the apron was slightly higher than the fixed floor, which resulted in the passengers, as the apron moved downward, “unconsciously” stepping off. It was reported that passengers found the machine so easy to use that very few riders — even elderly ones — felt the need to hold on to the railing during their trip. Hallé’s invention was perceived to be “of great interest, in terms of its innovation and its perfection of operation.”[2] The experience of riding the moving way was captured in a perspective drawing published in the 1897 edition of L’Année Industrielle, which depicted the stepped access platform and the extraordinary glass-walled balustrade that defined the inclined passageway (Figure 3).

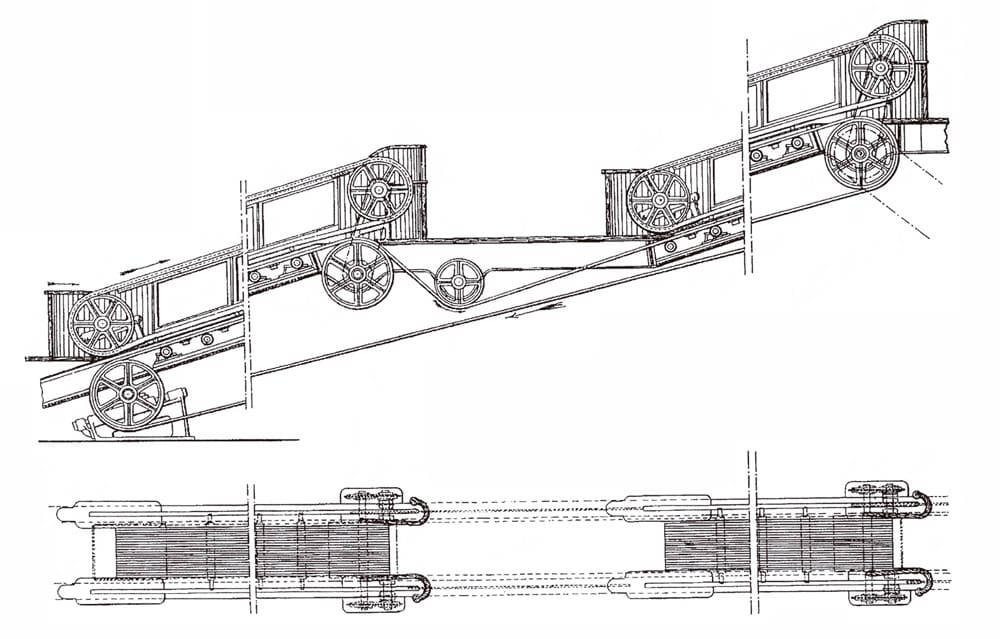

Further insights into the machine’s “perfection of operation” are found in a June 1898 article titled “Neue Fahrtreppe,” which was published in the German architectural magazine Centralblatt der Bauverwaltung.[3] The article details a section of the Grands Magasins du Louvre installation with an electric motor located in the basement connected to the top of the moving way via a complicated system of belts, pulleys and gears (Figure 4). A more logical location for the motor would have been below the second floor, adjacent to the drive gear. Although it is possible that concerns about noise prompted Hallé to isolate the electric motor, his patent drawings also depict a belted connection to an unseen motor located somewhere below the top of the moving way. The detail drawing also provides important additional information: the moving way had a horizontal run of 13.8 m and a vertical run of approximately 4.2 m. The latter number is 1 m lower than the given floor-to-floor height of 5.4 m due to the presence of a 1.2-m-high access landing on the lower level. The raised landing was necessary to provide room for the apron and handrail pulleys. Although unlabeled in the drawing, the moving way’s angle of inclination is approximately 17º.

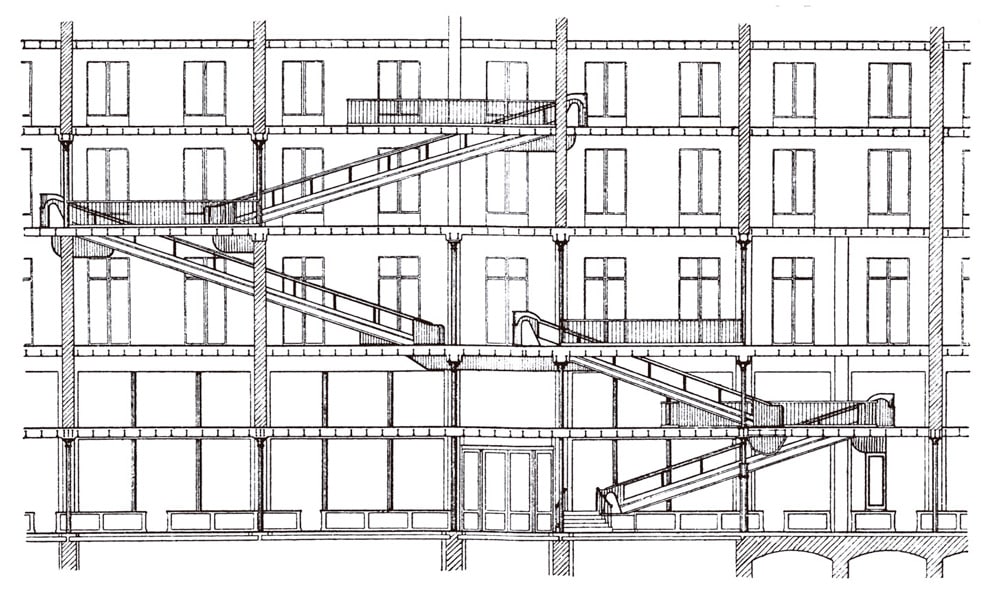

The article’s author was generally enthusiastic about Halle’s design. While he echoed the comment that it would be useful in buildings that had high traffic volumes, such as department stores and train stations, he also offered a new reason for its potential future popularity. He observed that it would be appreciated by people who disliked traveling while “locked into cages,” i.e., the confined space of the typical elevator car.[3] The only perceived limitations of Hallé’s system was that it occupied more floor space than an elevator and — due to its continuous operation — used more power. The author also speculated on its application throughout the Grands Magasins du Louvre. This speculation was enhanced by the presence of a building section that depicted a series of moving ways linking all four floors of the store (Figure 5). This drawing was the first published image that expressed the architectural potential of this new transportation system. The first- and fifth-floor moving ways resemble the machine depicted in the detailed section drawing. The third and fourth floors are served by two moving ways placed such that they employed a continuous apron: the hatched area below floor level indicates the passage for the moving belt. The estimated travel time from the ground to the fifth floor was less than 2 min.

In November 1898, a second moving way designed by Hallé was installed in another well-known department store; however, this time, the city was London, and the store was Harrods. In fact, Harrods had purchased the British rights to Hallé’s 1897 patent and contracted with A. Piat & Co. of Paris to erect one of his machines in its London store. Now dubbed “Harrods’ patented moving staircase,” the machine was opened to the public on November 16, 1898. The following day, the Pall Mall Gazette offered the following review:

“Such a getting upstairs there was yesterday as has not been hitherto attempted in this country. The novelty consists in an adaptation of the magic carpet of the fairy tale to the prosaic purposes of stairs. Thus, you do not so much as get up stairs as you get upstairs by the stairs going with you. The staircase is an endless leather band which runs on rollers with electricity for its motive power. You stand on the band, and the band ascends you at the rate of a foot and a half per s. When you have reached the height you desire, the moving staircase is warranted to unload you without inconvenience to itself or danger to yourself.”[4]

Several weeks later, another British newspaper printed a less poetic but more fulsome description of the staircase:

“It consists of a wide endless band of strong leather working on concealed rollers and forming a sloping floor, which, where it is available for passengers, travels in an upward direction. Persons wishing to pass from the ground floor to the one above have merely to step on to this ‘moving staircase,’ as it has been named, and allow themselves to be carried upwards. Rails on either side on which to rest the hands move at the same rate as the floor, and the ascent is intended to be accompanied without any movement on the part of the passenger, who, however, may, if there is nobody immediately in above him, hasten his progress by walking. The gradient is one in three, and the journey of some 40 ft. diagonally occupies about 25 s. Arrived at the top of the slope, the passenger steps easily and safely from the moving to the fixed floor. The carrying capacity of the ‘staircase’ is upwards of 3,000 persons an hour. . . . Electricity furnishes the motive power, and the cost of working is said not to be more than 9d per hour.”[5]

Harrods included references to the moving staircase in its advertisements, which reminded the public that the machine was “now running daily for the convenience of customers” and that Harrods was the “sole patentee for the United Kingdom.”[6] The installation appears to have closely followed the precedent set in the Grands Magasins du Louvre in that it featured a “silver plate-glass” balustrade that was “set in a case of polished mahogany.”[7] However, one significant difference was the disappearance of the stepped access platform used in the earlier machine. Either Hallé or A. Piat & Co. apparently modified its design to allow its placement at floor level (Figure 6).

Hallé’s successful installations in Paris and London led to his inclusion in the 1900 Paris Exposition, which offered an international showcase of moving-stairway technology. In addition to Hallé’s moving way, visitors also had opportunities to ride and examine machines designed by Jesse Reno, George Wheeler and Otis, and Jules le Blanc. The extensive display of this new transportation technology set the stage for its widespread adoption in the opening years of the 20th century.

This article is an excerpt from the author’s upcoming book A History of Escalators and Moving Stairways.

Figures 1 & 2: Jacques Hallé, “Moving Way or Stair for Transporting Persons and Goods,” U.S. Patent No. 602,008 (April 5, 1898)

Figure 3: L’Année Industrielle, Chapter 5: IV Les Escaliers Mobiles (1897)

Figure 4: Section drawing of the Grands Magasins du Louvre installation[3]

Figure 5: Section drawing depicting Hallé’s moving way used throughout the Grands Magasins du Louvre[3]

Figure 6: “Harrods’ patented moving staircase” (1901 advertisement)

References

[] Jacques Hallé. “Moving Way or Stair for Transporting Persons and Goods,” U.S. Patent No. 602,008 (April 5, 1898).

[2] “Plan Incliné des Magasins du Louvre,” L’Eclairage Electrique: Revue Hebdomadaire D’Electricité 11 (June 19, 1897): p. 605.

[3] “Neue Fahrtreppe,” Centralblatt der Bauverwaltung 18 (June 4, 1898):

p. 273.

[4] “Occasional Notes,” Pall Mall Gazette (November 17, 1898): p. 2.

[5] “A Novelty in Staircases,” The Aberdeen Weekly Journal (November 23, 1898): p. 7.

[6] Untitled Article, Pall Mall Gazette (December 14, 1898): p. 6.

[7] “The First Moving Staircase in England,” The Draper’s Record (November 19, 1898): p. 405.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.