A look at the titles and authors of the important American standard between its inception in 1921 and 1931

Members of the vertical-transportation industry often refer to the American elevator and escalator safety code as simply “the A17 code.” However, the first edition of the code, published in 1921, did not carry that well-known designation: “A17” did not appear until 1925 with the publication of the second edition. The code’s title also changed over the course of the first three editions, and its contents were (and have been since 1921) the subject of continual editorial review and modification. While the structure and membership of the team of authors responsible for drafting the code changed dramatically between the first and second editions, very few changes occurred between 1925 and 1931.

The story behind the development of the first edition of the American elevator and escalator safety code, as well as its 1917 predecessor (written by the Elevator Manufacturers Association of the U.S.), was the subject of an earlier article (“The First Elevator Safety Code: A Mystery,” ELEVATOR WORLD, November 2006). A later article examined some of the authors of the 1921 code (“The Code Writers of 1921,” EW, May 2008). However, neither included an examination of the development of the code over time. The history of the first three editions of the American elevator and escalator safety code also encompasses significant changes in the country’s regulatory landscape, in code writing and in elevator and escalator technology.

The first edition of the code was titled A Code of Safety Standards for the Construction, Operation and Maintenance of Elevators, Dumbwaiters and Escalators. The title page included a statement proclaiming that the code had been:

“Prepared by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) with the assistance of representatives of the U.S. Bureau of Standards, [the] Elevator Manufacturers Association of the U.S., [the] Elevator Manufacturers Association of N.Y., casualty and fire insurance companies, [the] American Institute of Architects (AIA), various related engineering societies, elevator specialty manufacturers, and independent engineers.”

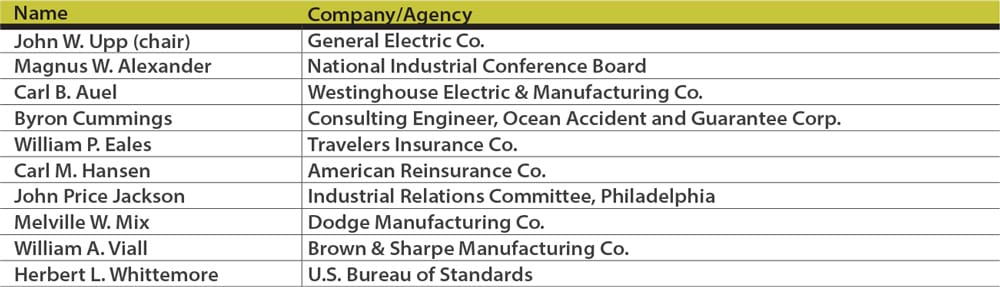

Further, more detailed authorial information was found on the next page, which described the code as “A Report of the Committee on the Protection of Industrial Workers.” Perhaps the most interesting thing about this committee was that not a single member had a direct connection with the elevator industry (Table 1). The November 1921 issue of Engineering World included an article titled “Mechanical Engineers Complete Safety Code for Elevators,” which outlined the approximately five-year process that produced the code. The article stated that John W. Upp, chair of the Committee on the Protection of Industrial Workers and manager of the Switchboard Department at the General Electric Co., had worked “untiringly on the editorial work involved in crystalizing the ideas expressed at the public meetings of the committee.” The article also noted that Upp’s assistants, John E. Molony and D.S. Morgan, also played an active role in editing the code.

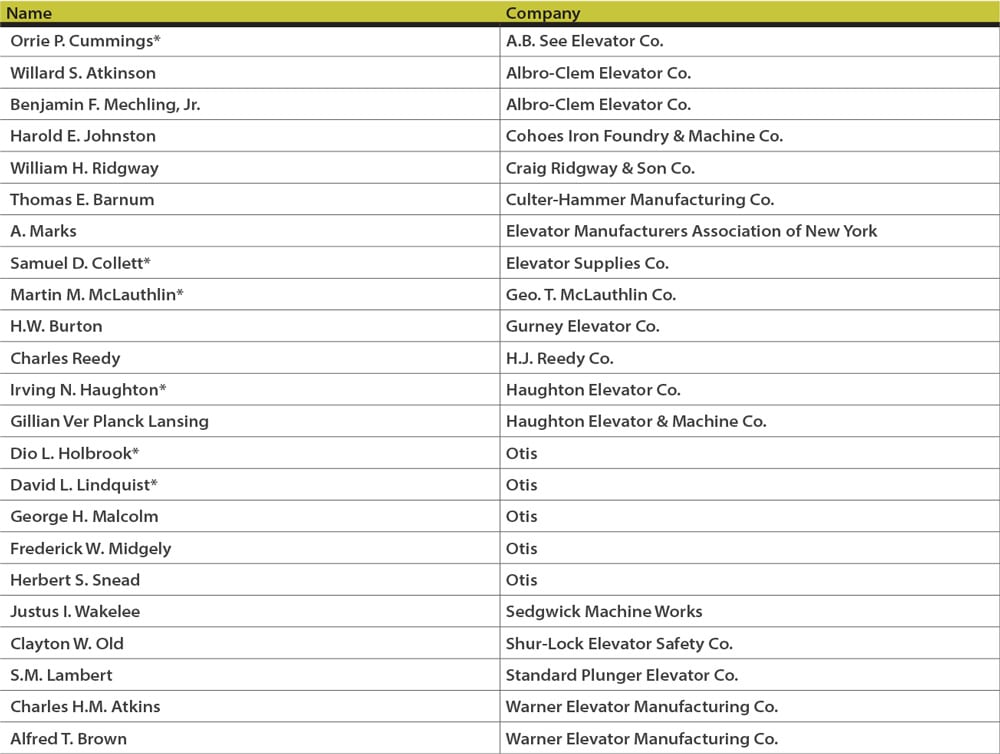

However, the Committee on the Protection of Industrial Workers had ample assistance in writing the code; it acknowledged the participation of a diverse group of 55 professionals, which included 24 members of the vertical-transportation industry who represented 15 elevator and elevator-industry-related companies (Table 2). The remainder of the participants included members of a diverse set of companies and state and federal agencies (Table 3). It is of interest to note that six of the non-elevator-industry participants were associated with General Electric and that New York dominated the “Government Agencies” category with five participants. In summary: although elevator-industry representatives composed 37% of the authorial team responsible for the first edition of the American elevator and escalator code, the effort was led by the Committee on the Protection of Industrial Workers (which had no elevator-industry representatives), and the code was primarily edited by non-elevator-industry engineers. And, although the elevator companies involved represented a broad geographic territory (west of the Mississippi), the majority of other participants came from New York or surrounding states.

The second edition of the American elevator and escalator code was the first to feature the designation “A17.” This was the result of increased efforts to develop and coordinate national codes, an initiative led by the American Standards Engineering Committee (ASEC), which was established in 1919 and was the precursor to the current American National Standards Institute. The full title of the 1925 edition of the American elevator and escalator code was A17-1925 Engineering and Industrial Safety Standards: A Safety Code for Elevators, Dumbwaiters and Escalators: Rules for Construction, Inspection, Maintenance and Operation. This was a subtle revision of the first edition’s title. The new title moved the critical subject matter (elevators, escalators and dumbwaiters) to the beginning and replaced the phrase “safety standards” with “rules.” In fact, the latter shift reflected the first edition’s actual contents. (The “standards” found in the 1921 code were referred to as “rules.”)

The title page of the 1925 code also stated that the code had been “Approved by the American Standards Engineering Committee as an American Standard” and that its production was supported by three “sponsor” organizations: the U.S. Bureau of Standards, AIA and ASME. Because the code had been developed under the auspices of the ASEC, the authorial team was described as a “Sectional Committee” charged with the development of “the safety code for elevators, dumbwaiters and escalators.” The sectional committee was chaired by Sullivan W. Jones (State Architect of New York), with Orrie P. Cummings (A.B. See Elevator Co.) serving as vice-chair, and John A. Dickerson (mechanical engineer, U.S. Bureau of Standards) serving as secretary. The committee was significantly smaller than the team responsible for the first edition. The 1925 committee roster identified 37 members and 10 alternates. Nineteen members of the 1921 authorial team participated in drafting the 1925 edition; thus, approximately 51% of the team were experienced elevator code writers.

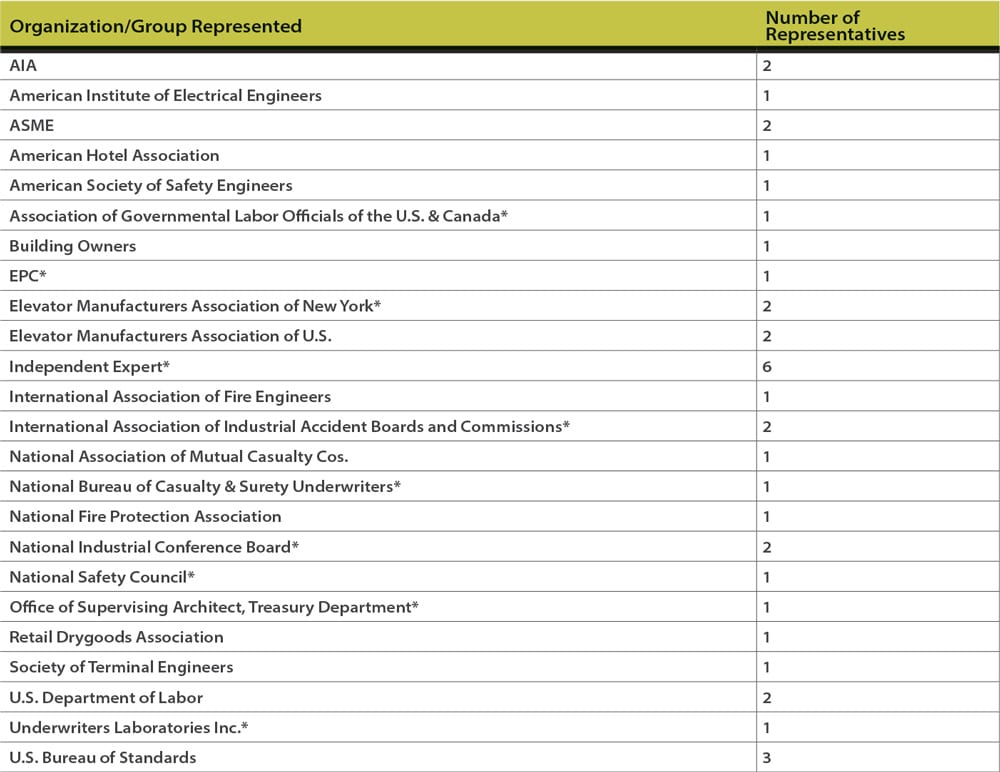

The 1925 roster also provided each committee member’s corporate affiliation and identified the group or organization represented. Whereas the introduction to the 1921 code referenced the involvement of numerous professional organizations, the 1925 code listed specific organizations and the number of committee members from each organization (Table 4). The presence of 24 different associations, boards and agencies reflects the professionalization of American industry in the first decades of the 20th century and the increasingly complex industrial landscape. One example of this specialized professionalism is that the Electric Power Club (EPC) was represented on the code committee. Founded in 1919, the “club” was dedicated to defining standard practices for electric motor and generator manufacturers. The EPC was given one seat on the committee, and it provided an alternate to ensure representation. The elevator industry was represented by nine committee members, seven of whom had also worked on the 1921 code (Table 5). Thus, although elevator-industry members made up approximately 24% of the committee’s membership, they represented a limited number of companies — six versus the 15 companies that had been involved in writing the first edition.

The third edition of the elevator escalator code appeared with a slightly modified title: A.S.A. A17-1931 American Standard Safety Code for Elevators, Dumbwaiters and Escalators: Rules for Construction, Inspection, Maintenance and Operation. In 1928, the AESC had reorganized and become the American Standards Association, and the code was produced under its auspices. The Sectional Committee responsible for the third edition was essentially identical to the previous committee in size and composition. It had 37 members and eight alternates, and the committee members represented a similar array of professional organizations. In fact, the only changes to the participating organization list was a shift in title from “independent expert” to “member at large” (Nils O. Lindstrom was the only committee member who remained listed as an independent expert), and the EPC was listed under its new name, the National Electrical Manufacturers Association. The number of seats allotted to each organization was also identical to that of the 1925 committee structure. This raises interesting questions regarding how decisions were made regarding the committee’s size and membership.

The 1931 committee also had only three new members (and four new alternates), and the elevator-industry representatives were the same who had served on the 1925 code committee. This continuity of code-committee membership quickly became a hallmark of the A17 code’s long history.

A parallel activity to researching this article has been the pursuit of biographies of all the code writers. This effort is slowly yielding results, which will permit further investigations into the authors, origins and writing of the A17 code.

Next month’s article will examine the content and organization of the first three editions of the American elevator and escalator code.

Table 1: 1921 Code: The Committee on the Protection of Industrial Workers

Table 2: The 1921 code’s elevator-industry participants (*participated in writing the 1921 elevator/escalator code)

Table 3: The 1921 code’s non-elevator-industry participants

Table 4: Participating organizations in the 1925 code’s Drafting Committee structure (*alternate member identified)

Table 5: The 1925 code’s elevator-industry participants (*participated in writing the 1921 elevator/escalator code; 1alternate for Thomas E. Barnum; 2alternate for David L. Lindquist)

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.