The Birth of the Modern Escalator

Dec 5, 2022

This History article looks at the lead up to June 1919 and the fervor surrounding the escalator’s introduction.

The end of the first era of escalator development was marked by two key events. The first was Otis’ purchase of Charles Seeberger’s patents and the trademark rights to the word “escalator” in 1910. The second was Otis’ acquisition of Jesse Reno’s patent rights and his Inclined Elevator Company in 1911. The former solidified Otis’ hold on the essential form of the escalator, while the latter provided access to a critical feature of future escalator design: the comb landing. The next step was the synthesis of the best features of both systems.

Research and development into the design of a new escalator began in late 1914, and the effort appears to have been led by Reno. Following the sale of his company and patent rights, Reno worked for Otis for approximately five years. During this period, he filed two escalator patent applications, the rights of which were assigned to Otis (the patents were awarded in 1916 and 1918).[1]

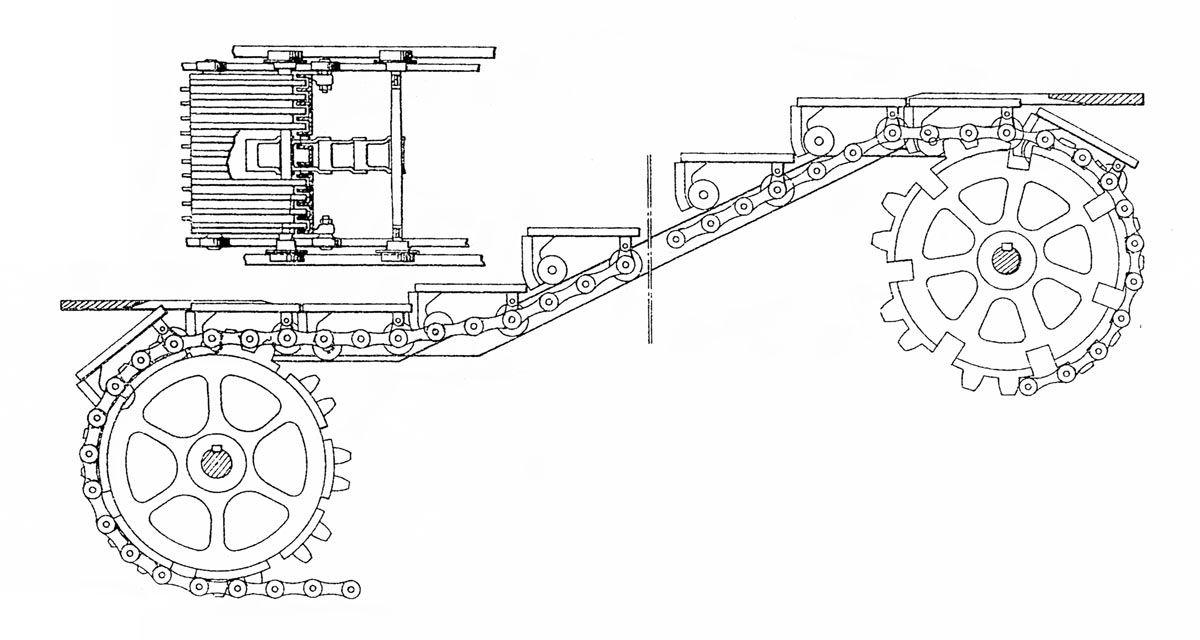

Reno filed his first application in March 1915. The patent focused on a new step design that included the application of wooden strips or cleats to Seeberger’s flat steps. The cleats allowed the steps to mesh with the comb plates at the escalator’s entrance and exit. Reno also proposed to employ vertical cleats on the steps’ risers. These cleats were spaced such that they meshed with the riser cleats (Figures 1 and 2). According to Reno:

“The purpose of this construction … is to prevent the passenger’s foot or apparel from entering and becoming caught between the back edge of one step and the riser of another, especially as the steps are changing their relative positions in passing to or from a landing.”[2]

Reno had, in fact, first proposed the use of tread and riser cleats in a 1906 patent for a stepped escalator.[3] However, in his second Otis patent, Reno abandoned the idea of using riser cleats and proposed using a smooth curving riser similar to that employed by Seeberger. The reason for this simplification in design was likely due to manufacturing concerns. The addition of cleats to flat steps was a relatively simple process. In the beginning, wooden strips were simply screwed on to the flat metal tread-plate. However, the installation of curving riser cleats would have been a complicated process that would have increased production time and increased costs. Thus, the implementation of what would become a standard feature of escalator step design would have to wait until the 1950s and the development of new manufacturing processes.

In early 1918, Otis contacted New York City’s Interborough Rapid Transit Company about the possibility of installing a “new type of escalator” in their Park Place subway station.[4] The transit company reported that Otis was “anxious to demonstrate the merits” of their new design and was “offering to provide and install it at exceptionally favorable terms.”[4] By July, Otis had received approval to install a “reversible, cleat step type, single file escalator … together with the balustrading … at the cost of US$13,250.”[4] This figure, which was approximately half the price of a typical escalator, reflected the level of Otis’ interest in building a prototype of their new design. The installation was completed in June 1919, and this event introduced the world to the modern escalator.

The level of public interest in the Park Place escalator was evident by the steady stream of references to its construction that appeared in the New York press between July 1918 and July 1919.

The level of public interest in the Park Place escalator was evident by the steady stream of references to its construction that appeared in the New York press between July 1918 and July 1919. One of these references was a May 13, 1919, article which announced that: “the escalator at Park Place Station … will ‘very shortly’ carry the rushing throngs of downtown workers from the subterranean depth of that station to the street.”[5]

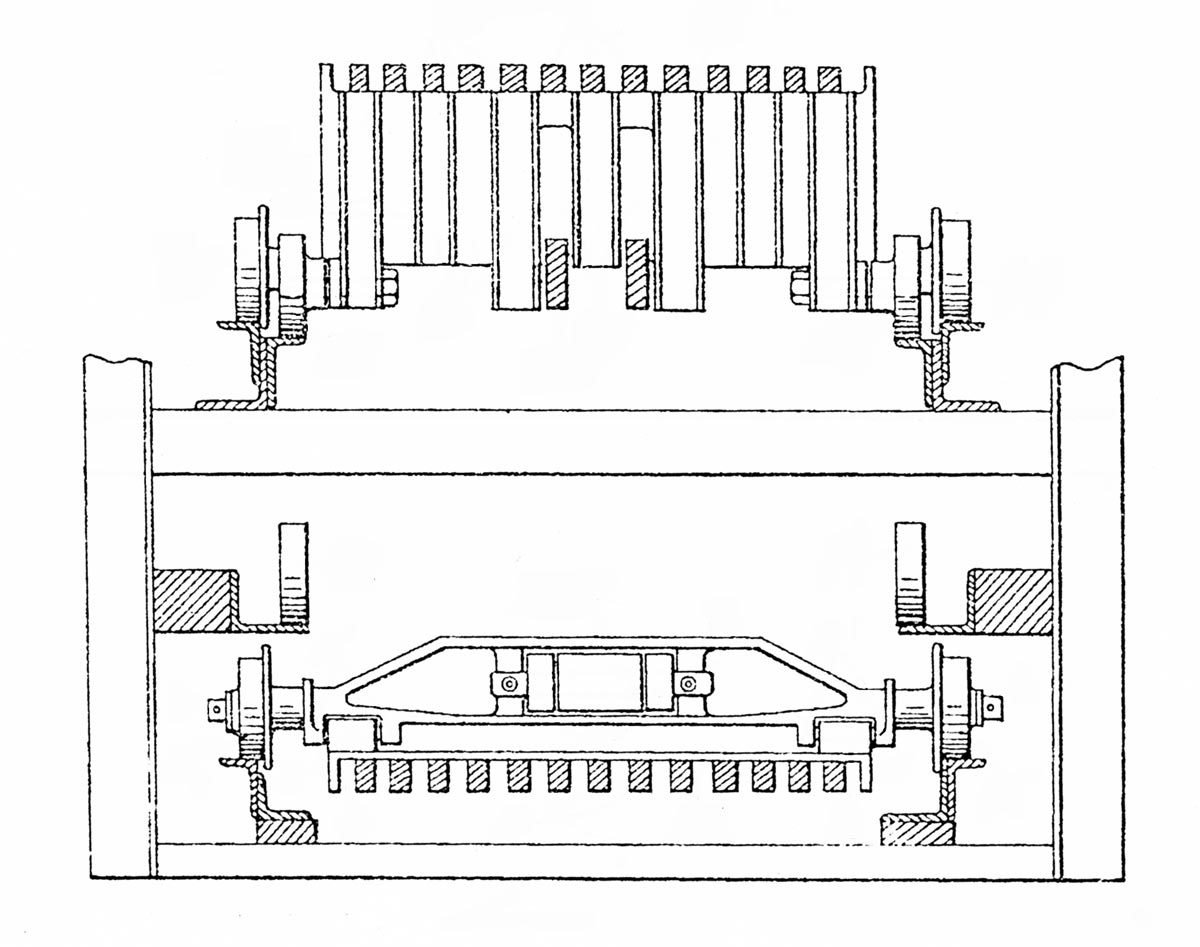

While the article also reported that “the escalator is of an entirely new type, known as the cleat-step escalator,” it failed to describe the features of the new machine.[5] The first detailed description appeared in the May 31, 1919, issue of Scientific American:

“Owing to the comparatively narrow platforms of the Park Place station, it was considered inadvisable to have the ordinary step escalator with side shunt at the exit point, and so a compromise was effected in the design of an escalator which is of the step type and yet combines the cleat form of exit and entrance. This is something decidedly new in escalators. The surface of the step is formed with deep cleats running parallel to the direction of the escalator and, as in the ordinary escalator, the steps run out on a common plane at the top and bottom to form the entrance and exit platforms, and at these points there are comb plates with the teeth of the combs projecting between the cleats of the steps, so that they will automatically lift the passenger’s feet off the step upon the fixed platform.”[6]

The article also included a drawing of the future installation (Figure 3). Although it is doubtful that the station’s design was the driving force in the development of this design — Otis was keenly aware of the problems associated with the use of the shunt landings utilized on Seeberger’s machines — it did constitute an ideal venue for testing the new design. The only drawback to this setting was its high public profile.

The pervasive awareness of the ongoing work was such that references to the escalator often appeared in unusual contexts. In a review of the work of movie director Alan Dwan, pioneering movie critic Harriet Underhill commented on his sense of humor, as displayed in the film Bound in Morocco starring Douglas Fairbanks and Pauline Curley. Underhill recalled the scene “in which the heroine, rescued from the harem, wore a Liberty Loan button and with tears in her eyes gasped out, ‘Is the subway finished yet?’[7] Underhill observed that, if the line were brought up-to-date, it would have read: “Is the escalator at Park Place finished yet?”[7] When the escalator finally began operation on June 4, its inaugural running was not what New Yorkers expected:

“Thirty thousand dollars’ worth of hitherto immobile steps of the Park Place station of the West Side subway took their maiden journey yesterday, carrying no passengers. Hundreds of people alighted from the trains at the station and heard the creaking of the escalator. The day being warm, they pictured themselves riding up in cool comfort instead of climbing the four flights of stairs. But on investigation they found their way barred and saw that the movement of the stairs was for the benefit of a blue-shirted gentleman testing out the convenience.”[8]

The reference to a price tag of US$30,000, more than twice as much as the contracted cost, raises questions regarding who was responsible for the cost overrun. If, in fact, Otis adsorbed the additional costs, it would serve as further evidence of their commitment to building the prototype of their new design.

Unfortunately, the identity of the “blue-shirted gentleman” riding the escalator is unknown (he was most likely an Otis engineer). What is known is that the operational tests continued for three weeks, with the escalator finally opening to the public on June 24. The New York Tribune reported that “thousands” of commuters:

“rubbed their eyes and heaved thankful sighs of relief when they … found that at last the escalator was in operation. It has taken months to build this energy saving device, and at times it appeared that work had been abandoned. There are seventy-nine steps between the platform and the street level and the escalator takes care of all but sixteen of them.”[9]

Its opening was not, however, without problems, and it was apparently not reliably in operation until late July, a fact recounted in a colorful manner in the local press:

“The Park Place escalator is the picture of ruddy good health after its severe attacks of spring fever. The new escalator attached to the Seventh Avenue subway service is now up and around and about able to do a full day’s work without more than once or twice threatening to turn Bolsheviki and labor not at all. There were times during the spring and early summer when it looked as though the escalator were going to die on Mr. Shonts’ hands. It could scarcely sit up, and moved only with a convulsive shudder. But at length the blue jeans clinic that worked upon the escalator succeeded on lowering its blood pressure, retarding the action of its heart and by brisk massaging restored the use of its upper and nether joints. As a result, there isn’t an escalator in town that escalates any more freely than the one at Park Place.”[10]

This enthusiastic appraisal may require a bit of decoding for modern readers. “Mr. Shonts” was Theodore P. Shonts, president of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company and, of course, the reference to Bolsheviks and labor serves as a reminder of the state of American politics at the time.

In addition to endorsing the escalator’s successful operation, the article also offered an assessment of its appearance and daily performance:

“The Park Place escalator is tall and thin, somewhat as though it had been on a rigorous diet. Its two-foot beam permits only one passenger at a time to enter upon the sprightly journey upward, and on the morning rush hours, as the customers form a long queue awaiting their turn, each to save sixty-eight steps, the appearance is not unlike the opening of the Ziegfeld follies.”[10]

Although the initial contract had called for a 4-ft-wide machine, the Park Place escalator was only 24 in. wide handrail-to-handrail. The steps were 18 in. wide, with a 16-in. tread and 8-in. riser. While the reason for the reduction in size is unknown, the change brought the new machine in line with the majority of escalators Otis provided for the New York Subway. In fact, between 1900 and 1930 Otis built fewer than 10 4-ft-wide escalators for use in American transit systems. Their default width for this application in the U.S. was 2 ft, whereas their default width for European transit systems was 4 ft. The larger size proposed for Park Place may have represented an attempt by Otis to develop a single model that could be used globally.

In spite of the difficulties and cost overruns involved in this project, Otis was very likely pleased with the positive reception their new escalator received. The Park Place installation may have also provided a baptism-by-fire for a young engineer who would go on to play a leading role in Otis’ future escalator R&D efforts. Samuel G. Margles (1889-1978) joined Otis in 1911 immediately following his graduation from Cooper Union with degrees in civil and mechanical engineering. He was initially employed as a draftsman in the construction department and was transferred to the engineering department in 1918. In 1919, he began to work on escalators and was likely assigned to the Park Place project. Margles’ pioneering work on escalator design will be the subject of a future article.

References

[1] Jesse W. Reno, Conveyer, U.S. Patent No. 1,178,102 (April 4, 1916) and Jesse W. Reno, Conveyer, U.S. Patent No. 1,288,196 (December 17, 1918).

[2] Conveyer, U.S. Patent No. 1,178,102 (April 4, 1916).

[3] Jesse W. Reno, Inclined Elevator, U.S. Patent No. 817,338 (April 10, 1906).

[4] Report of the Public Service Commission for the First District of the State of New York for the Year Ending December 31, 1918, V. 1, Albany: J.B. Lyon Company (1919).

[5] “Your Town,” New York Tribune (May 13, 1919).

[6] “The Park Place Subway Station Escalators,” Scientific American (May 31, 1919).

[7] Harriet Underhill, “In Which Allan Dwan Tells All About Supervision, New York Tribune (March 23, 1919).

[8] “Your Town,” New York Tribune (June 19, 1919).

[9] “Your Town,” New York Tribune (June 24, 1919).

[10] “The Park Place Escalator,” New York Tribune (July 27, 1919).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.